Introducing Arieh Allweil

INTRODUCTION

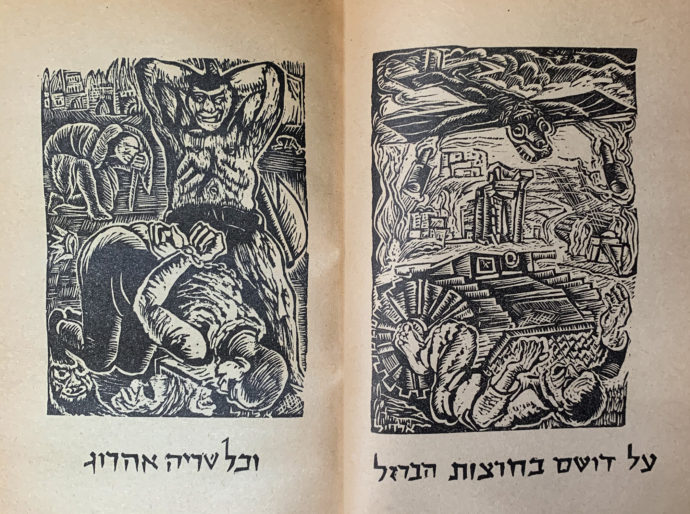

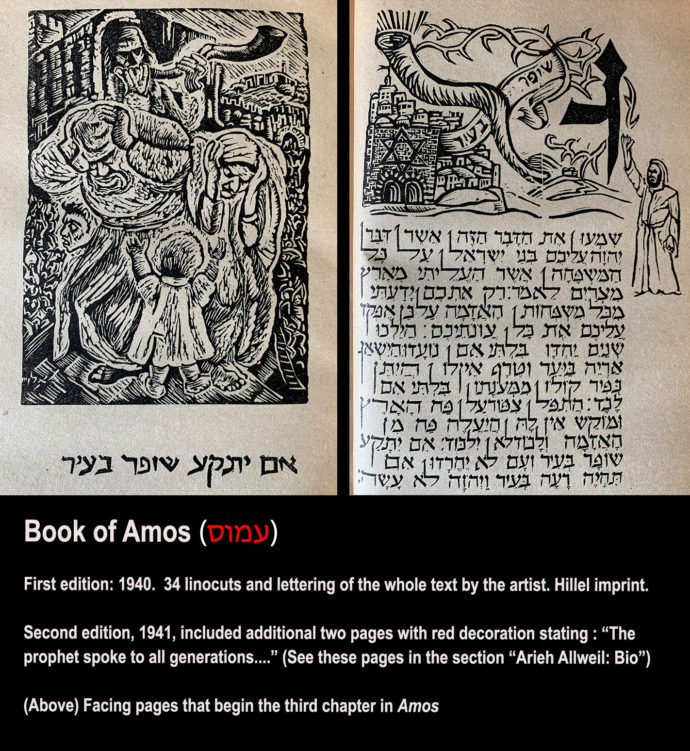

Last April the Israeli book dealer from whom I bought Erich Glas’s Leilot (See: http://www.scottponemone.com/eretz-israel-narratives-in-relief-prints/) alerted me to his new eBay offering. He touted that the linocuts in Arieh Allweil’s The Book of Amos, 1940, were better than Glas’s and better than the relief prints in another Eretz Israel book he also sold me: BeShir oovCheret (See: http://www.scottponemone.com/kibbutzim-in-eretz-israel/). While I won’t necessarily place Allweil’s work over the others’, I was immediately fascinated by his images. With images like the one on the right with its plane dropping bombs and a tank crushing a man, Allweil brought his account on the Old Testament Prophet Amos into the horrors of mid-20th-century Europe.

Indeed, I was interested in having a copy of The Book of Amos, but his copy was spotted all over with foxing. Luckily, another seller in Israel had a much cleaner copy on eBay for much less money. That’s just how things work out.

When my copy finally arrived in late May (overseas transport of mail had all but stopped during the early COVID shutdown days), I emailed images of the title pages, the colophon and some of the plates in Amos to Iddo Gal (a grandson of Erich Glas) and asked him if he would translate the Hebrew into English. He agreed in early June. While the titles pages and colophon were written in contemporary Hebrew, he said the text under the plates were straight from the Bible. So he added this cautionary note: “This is very hard to translate directly because …. it is ancient language, which at the time was very terse, many words had underlying meanings or hidden connotations or different meanings then compared to modern Hebrew (think of text in Middle-Ages English). So sometimes what you can do is convey some of the spirit of the text, but actual translation is not possible for non-scholars like us, and even then, you’d need side notes to help grasp the full meaning.”

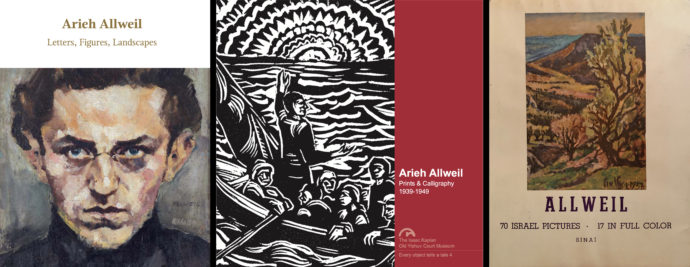

In early July, Gal brought up the name of Galia Bar Or, who he described as “a leading curator and art historian in Israel, very knowledgeable and creative, and just a nice person,” and added, “I met her a couple times; she visited us here at home looking for artwork by Erich Glas, because she organized a big exhibit in Berlin a few years ago on architecture and building design in kibbutzim.” He noted that in 2015 Bar Or, Galia curated the exhibition Arieh Allweil: Letters, Figures, Landscapes at the Mishkan Museum of Art. She also wrote the accompanying catalogue. He passed along an email address for her. (Her booking in English is available online: LINK)

So I wrote to Bar Or and told her about my interest in Allweil and gave examples of my blogging. Not only did she express interest but evidently she talked to Ruth Sperling, a daughter of Allweil’s, and provided an email address for her. Sperling soon replied: “I am really glad to tell you about the works of my father.” She also introduced me to the names of other books her father illustrated with linocuts in the years 1939-45. In turn she introduced me to Galia Gavish, an artist and curator who had written two books, one of which–Arieh Allweil: Prints & Calligraphy, 2007–caught my eye. Bar Or later told me in an email, “I was working in the Mishkan for 30 years, directing and curating the exhibitions.”

Both Galia Bar Or and Galia Gavish sent me PFDs of their books. I did more poking around online and talked to a collector in Florida who lent (with option to buy) me three Allweil-illustrated books: a rebound copy of The Book of Esther, an unbound copy of The Book of Lamentations, and a later copy of Anonymous Jew. Recently I purchased from another Israeli book dealer signed copies of The Book of Ruth and The Book of Esther. I wonder how long it’ll take to receive them.

Ergo, what began as an attempt to present one important book by Arieh Allweil has become a grander effort. With the blessings of Ruth Sperling, Professor of Genetics at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and her sister Nava Rosenfeld, a retired architect, I’ll attempt a series of ART I SEE blog posts, starting today with an overview of there artist and a listing of his books from 1939 to 1949. Subsequently, starting with Amos, I’ll present Allweil’s book separately with images of all his linocut or lithograph illustrations.

All images from Arieh Allweil’s books are presented courtesy of the Allweil Estate.

(Left) Galia Bar Or, “Arieh Allweil: Letters, Figures, Landscapes,” Mishkan Museum of Art, Ein Harod, Israel, 2015. (Middle) Galia Gavish, “Arieh Allweil: Prints & Caligraphy, Books 1939-1949,” The Isaac Kaplan Old Yishuv Court Museum , Jerusalem, Israel, 2007. (Right) Arieh Allweil, Max Brod and I.M. Lask, “Allweil,” Sinai Publishing, Tel Aviv, Israel, 1955.

Arieh Allweil: Bio

The following is a short biography of the artist Arieh Allweil up to the year 1949, when he finished the last of the books covered in this post. I rely on the above three books. Authors Galia Bar Or and Galia Gavish made their books available to me via PDFs. A hard copy of Allweil was a gift from the artist’s daughters, Ruth and Nava.

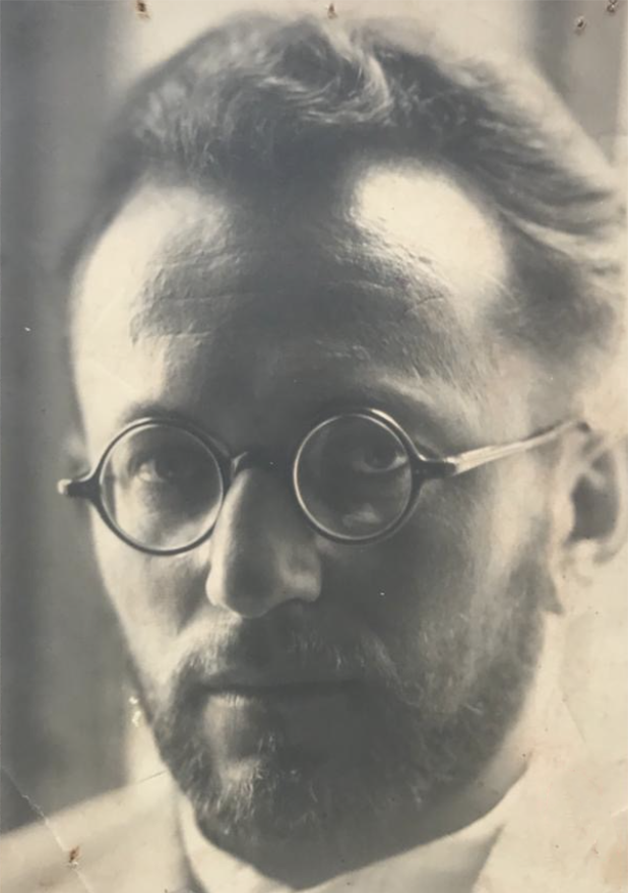

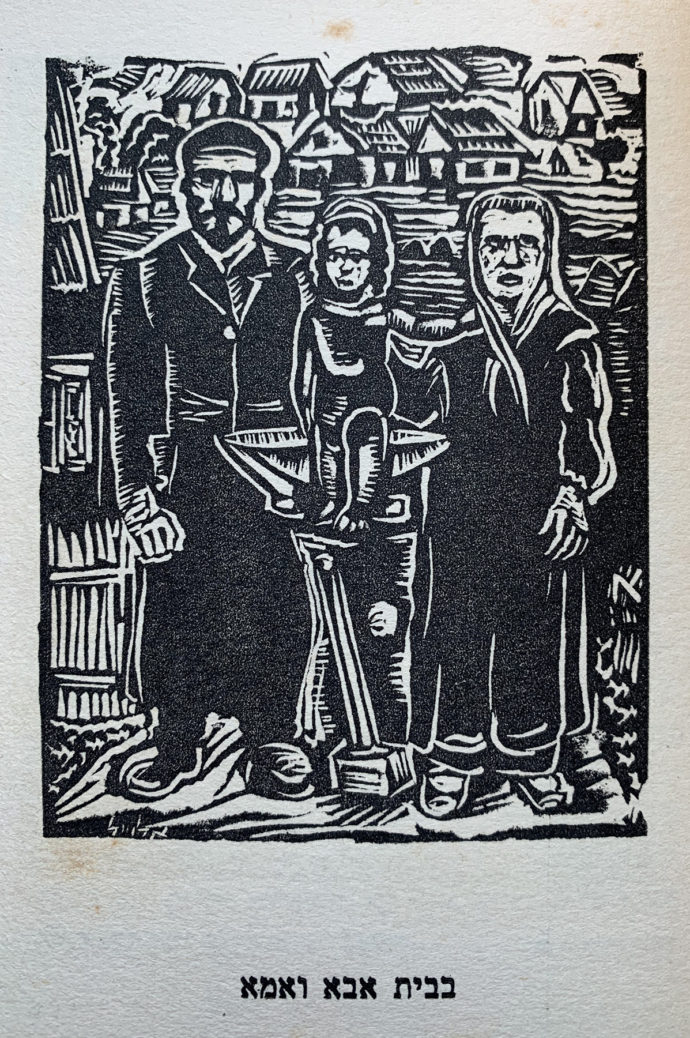

Arieh was born in 1901 in Bobrka (Bobroysk), Galicia (now in Ukraine). His father was a metalsmith. To the right is his family portrait, the first linocut in his 1939 book The Anonymous Jew. In her book Galia Bar Or describes this plate: “Titled In Father’s and Mother’s Home, it shows the figures of his mother and his father the metalsmith in a condensed structure in which the parents look like large wings spreading protectively on either side of the little boy seated on the metalsmith’s anvil.”

In his autobiographical remarks that opens the book Allweil, the artist said:

I do not remember from my childhood the ‘traditional fear of Goyim.’ I do not remember degenerate Jews in my village, except a few naive idiots. Cheerfulness rules in my house, which was full of work, from sunrise on. I ran about in fields and woods, the humming of bees in my ears….

When the First World War broke out, the old world of the ‘Austrian idyll’ finished ‘The gods had begun to thirst for blood.’ When the Russians invaded Galicia, my father bought horse and cart, packed as much of his belongings as he could and we set out….

Arriving in Vienna, the European city, I saw the last glimmerings of the sinking kingdom, and I saw for the first time libraries, museums, theaters and concerts. I joined the youth movement, Hashomer Hatzair and this brought me back to me people.

But by 1919 he returns to Bobrka to establish a branch of the Hashomer Hatzair there. According to Bar Or, he led this branch “from the basement of his parents’ home, to the chagrin of the Jewish establishment in the town and of many of the young members’ parents. Later, he established the movement in Lvov and in the entire region, earned his living by teaching Hebrew, and was considered a zealot of the language.”

(Jewish Virtual Library website (link) states: “Hashomer Hatzair, the initial Zionist youth movement, was founded in Eastern Europe on the eve of the First World War. Many Jewish youth, affected by the process of modernization which had begun among Eastern European Jewry, sought a means of maintaining their Jewish identity and culture outside the stifling barriers of the shtetl and of Orthodox Jewish life. On the other hand, they were troubled by the crumbling of the foundations of society around them and by the growing anti–Semitism which threatened their very existence.”)

As a Hashomer Hatzair member, he emigrated to Eretz Israel (Palestine) in 1920 and helped found the Bitanya Ilit kibbutz. There he became a “halutz,” a Zionist agricultural pioneer. But despite his enthusiasm for Hashomer Hatzair, he soon realized that his future was to be a painter not a farmer. In Allweil, he wrote: “I decided to become a painter at the time when I was living in a settlement of pioneers on a mountain in Galilee. We were preparing the earth and digging holes to plant grape-vines and olive trees. We were on the mountain, and beneath, the meandering Jordan flowed out of the Kinneret, and the mountains Golan and Bashan closed us in.”

Galia Gavish wrote in her book:

Arieh Allweil left Palestine to study at the Kunstgewerbeschule, a prestigious art academy in Vienna (1921-1925) (Oscar Kokoschka had studied there between 1903 -1909). Kokoschka had rejected the ideal that prevailed in academics, the overdone Jugendstil style. He viewed blunt German expressionism as a more appropriate form of expression after everything Europe had undergone in WWI. By the time that Arieh Allweil came to study at the academy, the German expressionist stream had already taken hold….

The artists used many sketching techniques as preparation for woodcuts and oil paintings. After WWI, many of the artists returned from battle, shocked and unable to break free of the horrific sights. They were opposed to wars and dictatorships and in favor of hard-working laborers. Their world view suited that of Arieh Allweil , and he was quickly accepted by them to the Kunstschau group and even exhibited with them.

Galia Bar Or noted in her book: “…in 1924 he joined the avant-garde Kunstschau group–a circle of artists that had originally formed around Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele. Most of the members of the group were older than him, had already been active in the art world for some time, and were known on the art stages throughout the world. They received him, the only Jew in the group, into their circle and their discourse; they gave him their trust and included him in their activities. He stayed there for four years….”

Sperling said in an email that his father in his autobiographical essay mentioned he exhibited with the group in 1924 and 1925. “We have a catalogue from 1925,” she said, “of an exhibition of Austrian Art of the quarter century, in Vienna. Allweil exhibited there. He exhibited five paintings together with the Kunstschau group. There is a limited number of pictures of exhibited paintings, including from Klimt and Schiele, and from Arieh Allweil.”

In Allweil, the artist wrote: “Kokoshka, who had seem my pictures in Dresden, disliked these which showed cubist tendencies. ‘You cannot feel like that when you came from a small village, where you were taught by a Rabbi,’ he said. Once a week I visited a rich art-lover Neumark with this [Kunstschau] group and he helped me go to Paris.”

In an email Sperling offered evidence that despite Kokoshka’s comment her father was not a country rube. She wrote: “Although he was born in a small village, Allweil studied school in Levov and high school in Vienna.”

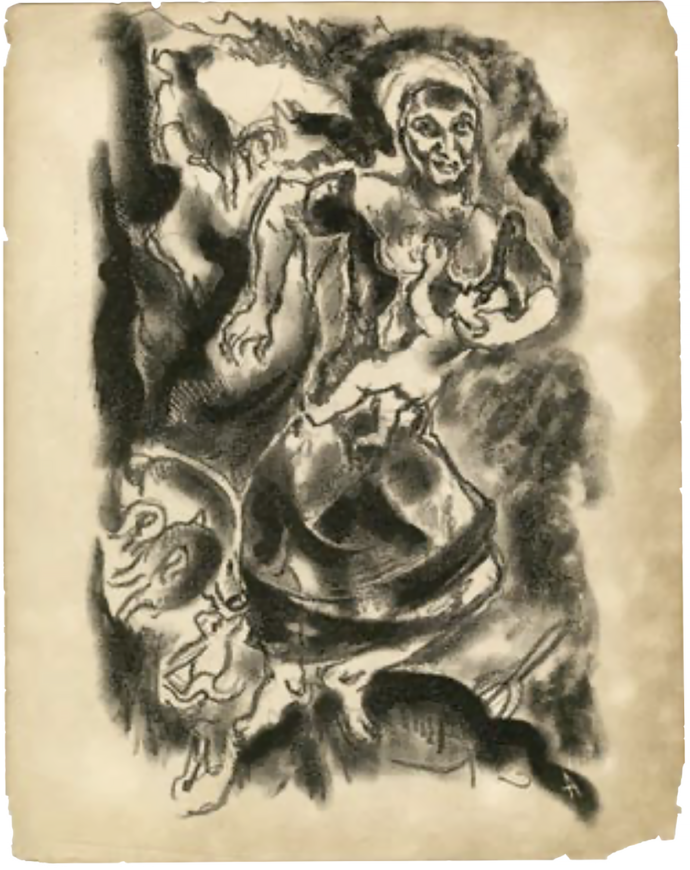

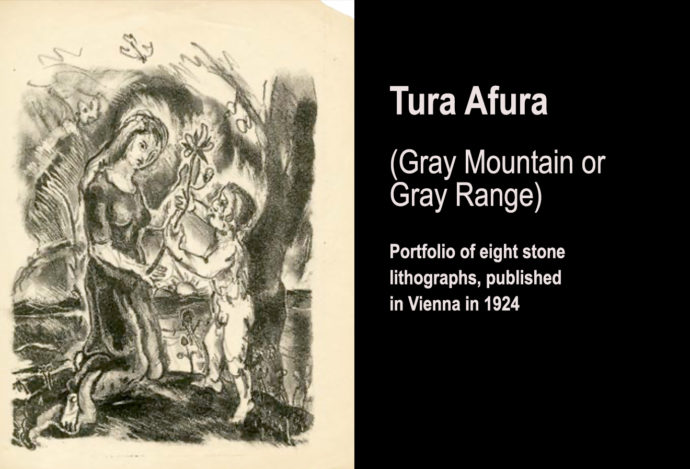

While in Vienna he did produce a remarkable album of eight lithographs: Tura Afura (Gray Mountain or Gray Range). Here is Bar Or’s description of the litho shown there: “We see a woman, perhaps an allegorical figure, with an overgrown baby pressed to her breast and other bodies clutching and sucking the marrow of her falling body, as though she were already a ghost. The fascinating choreography of the clutching and the twisting responds to the structure of the background, which is done as though with a single free brushstroke that imprints spiral movements in the thick black ink.” In his autobiographical remarks, Allweil mentioned that he created this album but gave no details.

Allweil also wrote: “In 1926 I returned to Israel by way of Paris and Italy, and I was again on a ship. The smell of tar and of sea water reminded me of the pioneer songs of my first emigration…. Would I at last realize my dreams from Bitanya about painting.” He then went on at length about the difficulty of painting in Palestine and he talked about the various venues he visited and did paintings from. For instance: “Jerusalem is monumental and heroic, but villages and fields appeal to me more.”

“During the 1930 summer vacation,” Bar Or wrote, “Allweil visited his parents in Galicia, and also traveled to Austria and Poland. In the summer and autumn of 1931 he stayed at his parents’ home in Galicia once again. One purpose of his travels in Europe was to collect materials on Jewish art; another was to be active among Jewish educational institutions. He visited his parents again in the summer of 1934, and the last time he saw them–according to the documents in his estate–was when he visited them in 1936.”

Allweil Family early 1950s: Rachel and Arieh in back with (from left) Hillel, Ruth and Nava in front. (Photo courtesy of Ruth Sperling and Nava Rosenfeld.)

Galia Bar Or noted, “He was one of the founders of the Tel Aviv Museum [in 1933] and of the Midrasha Art Teachers’ College when it was first established in Tel Aviv.” She mention his two marriages: “When his solo exhibition opened at the Tel Aviv Museum in 1933 he was already married to the poet Esther Raab.” They divorced in 1935. Then she wrote: “In 1938 Allweil married Rachel Bugrashov, a painter, and the daughter of Dr. Haim Bugrashov. They lived in Tel Aviv, and over the years had three children: Ruth, Nava and Hillel. Hillel, who was born in 1947, was named after Arieh’s father.”

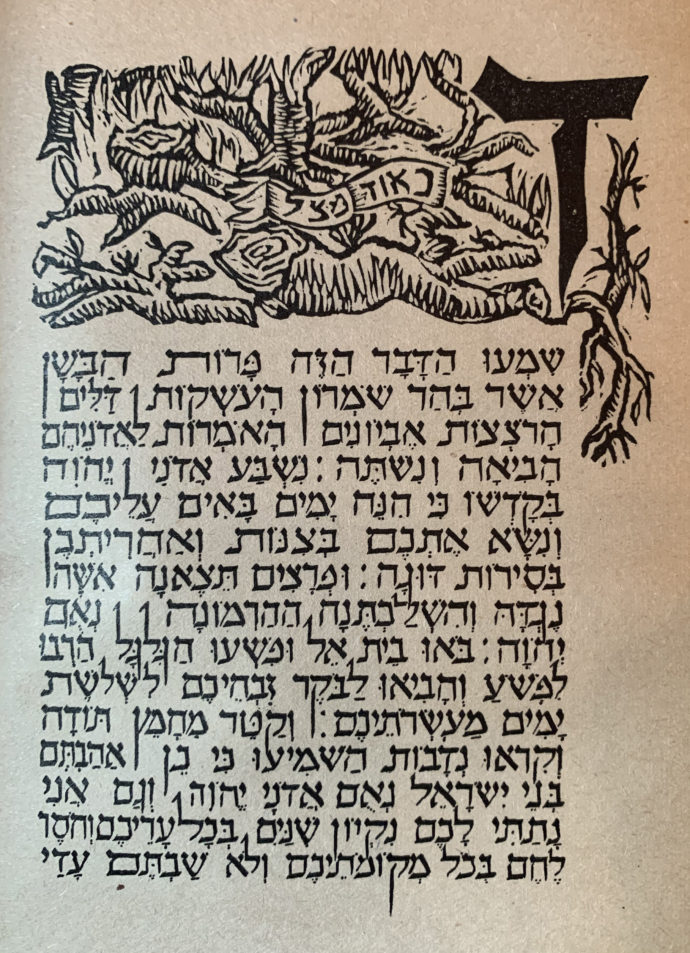

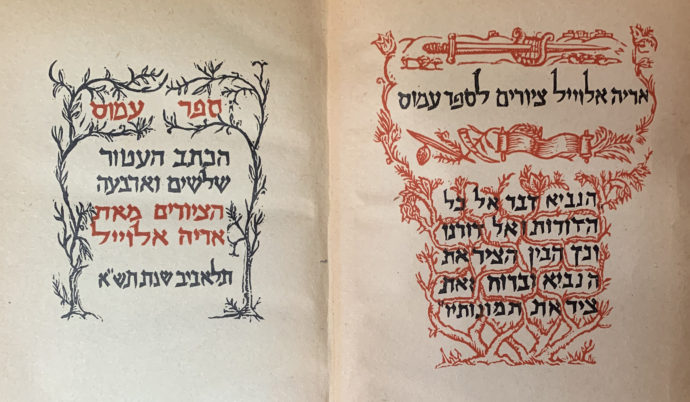

The title pages of Arieh Allweil’s 1941 “The Book of Amos.” He made both the pictorial elements and the Hebrew letters as linocuts. These pages were added to “Amos” that was first published in 1940.

But since my focus for future Allweil blog posts will be the books he illustrated with linocuts–like those from Amos that introduces this post–I turn to his years 1939-49.

In his autobiographical essay, Allweil wrote: “My real aim is to paint the Land of ours from dawn to sunset, to be another Jewish painter that draws letters and images from the Bible in our days as of old. I am very fond of the Sephardic Hebrew letter–written, cut in marble or engraved in copper.” No wonder that beginning in 1939 Allweil would be producing mostly biblical themed books with vigorous linocuts and his own Hebrew font.

Galia Bar Or wrote: “Allweil made a distinctive contribution to Israeli art in two very different and contrasting fields: a new visual interpretation of biblical texts by means of black-and-white prints and calligraphy, in works that in a unique and topical way express his suppressed anguish at the horrors of the Holocaust period, and an original development of richly colorful and pictorial landscape painting…. The dialectical relations between these two orientations in Allweil’s oeuvre, nightmare and utopia, hints its complex character….

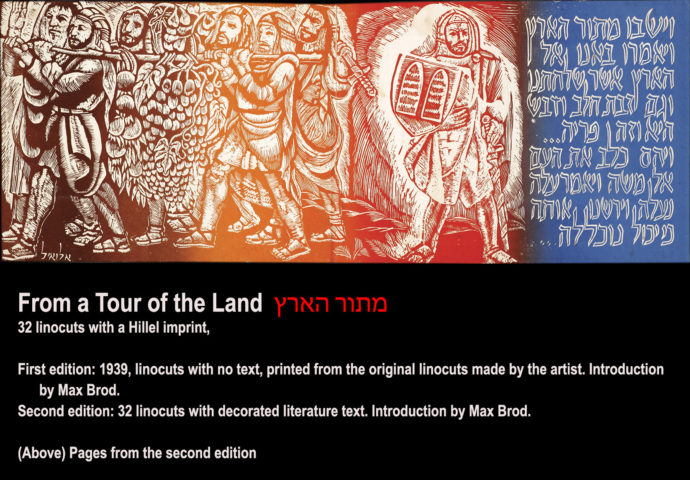

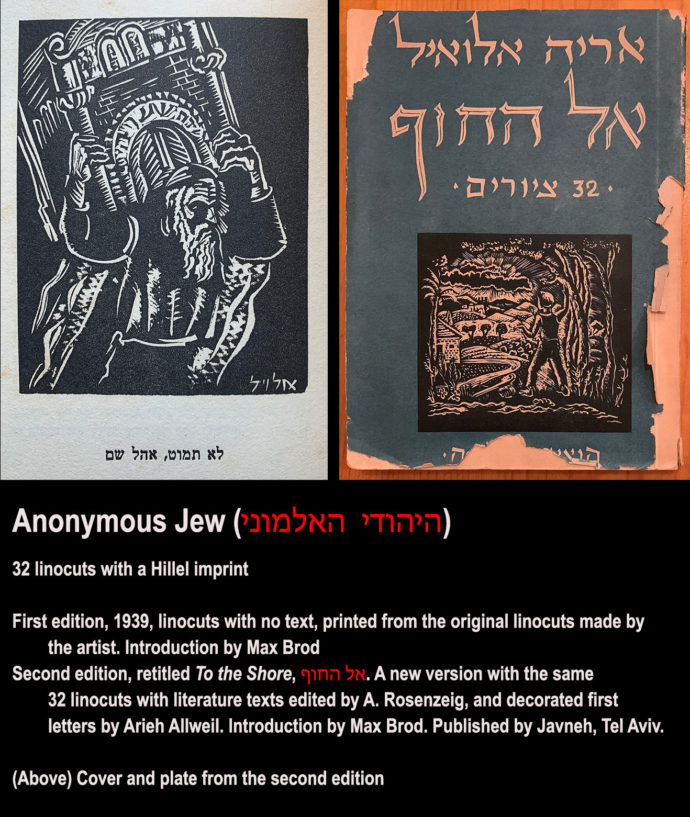

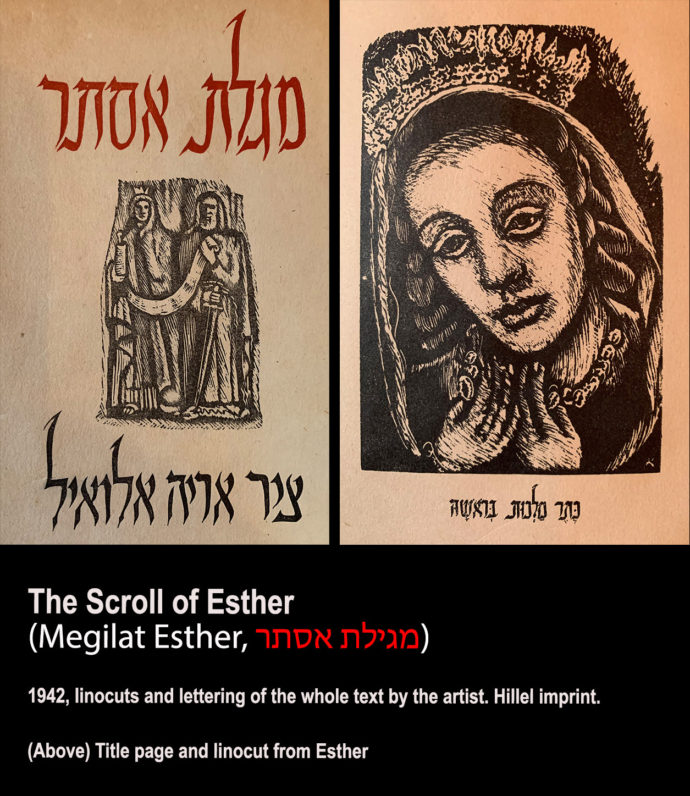

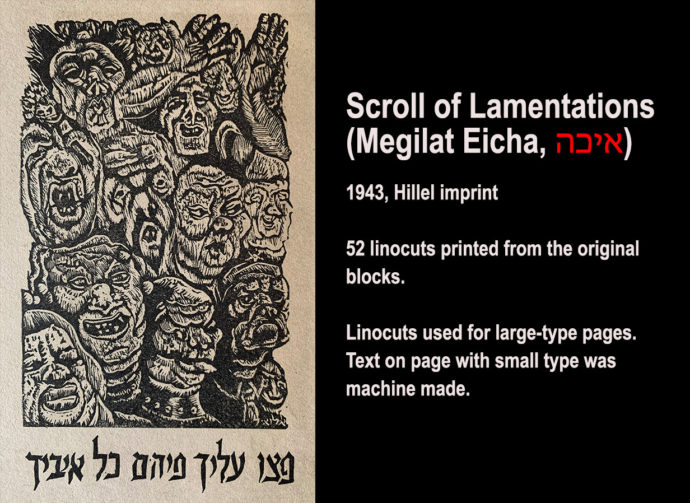

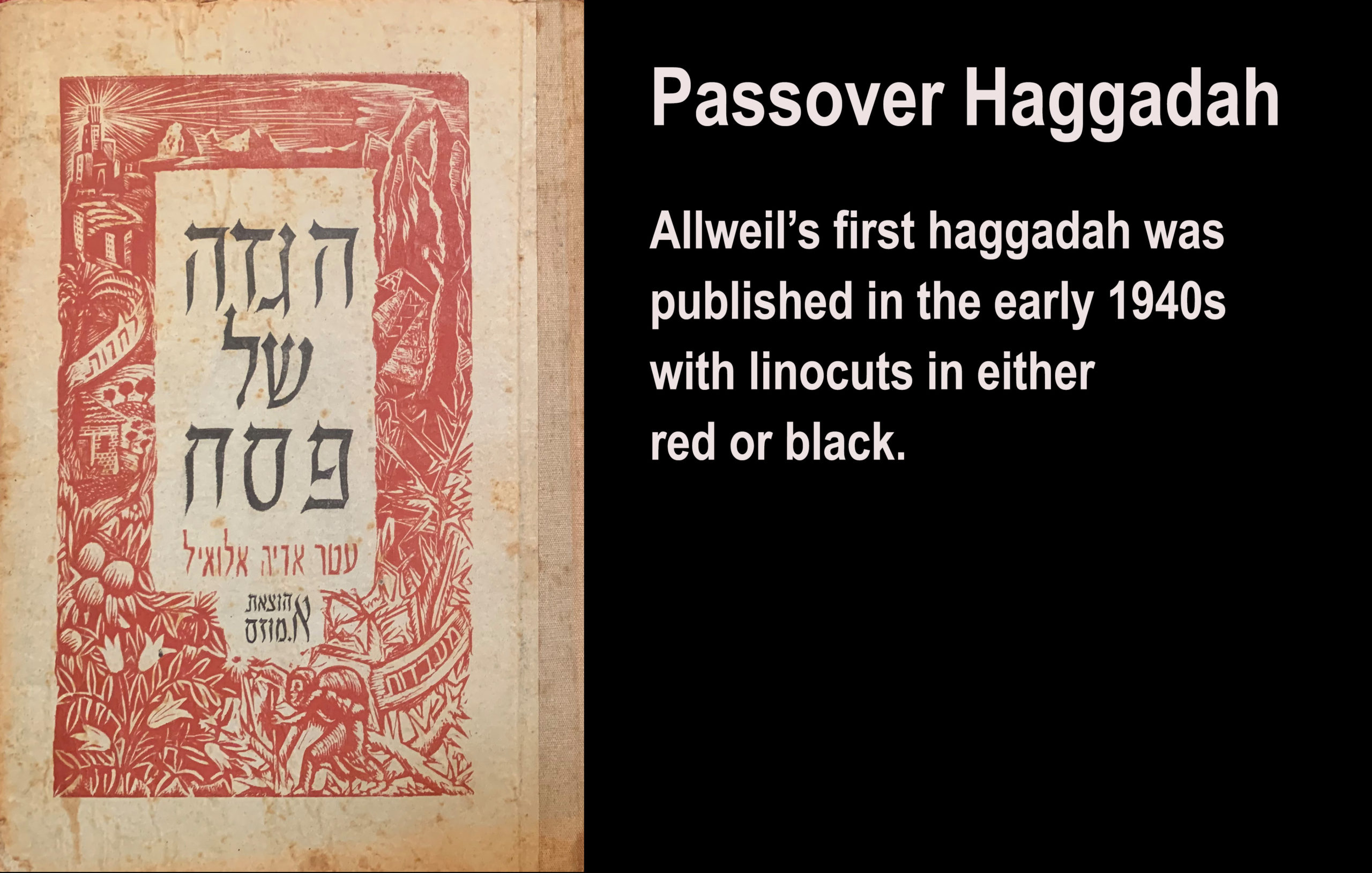

“In 1939 Allweil established an independent publishing firm named ‘Hillel’ [after his father], and in the course of the war years and the Holocaust he published books that he produced with his own hands, among them The Anonymous Jew, Lamentations, Amos and Esther. He hand-gouged the texts on linoleum, interspersed the illustrations with allusions to events of the period, printed the sheets, cut, folded and bound the books all by himself.”

And Galia Gavish wrote: “He produced his illustrated books in a German expressionist style and in a Jewish spirit. Similarly to European artists, who used Greek mythology as an political allegory for their period, Allweil drew his allegorical materials from the Jewish classics the Bible. Allweil’s choice of the Scrolls of Esther, Lamentations and Amos, and the Passover Haggadah, are significant. Each of these books has an apocalyptic atmosphere with a hopeful ending.”

In his essay in Allweil, the artist wrote: ” ‘The prophet spoke to all generations, and to our generation… and in that spirit, the painter painted his pictures.’ One of the writers advised me to quote theses words as a motto in my illustrations to the book of Amos. This text I wrote with my personal lettering, and opposite every written page I printed a linocut. I similarly made three megillahs: Ruth, Esther and Lamentations. I put the figures into our home, the people are our brothers, our parents and our children.”

He placed “the prophet” quote in five lines intertwined by vines on the righthand page from Amos shown above. Iddo Gal’s translated those pages for me. Using alternating red and black type, the lefthand page reads: “Book of Amos The script decorate [with] thirty-four paintings by Arieh Allweil Tel Aviv year 1941.” Evidently here Allweil used “paintings” to indicate artwork. In the colophon the artist was more specific: ” ‘Book of Amos’ printed with the original plates of linocuts made by the painter and facsimiles of his writing.”

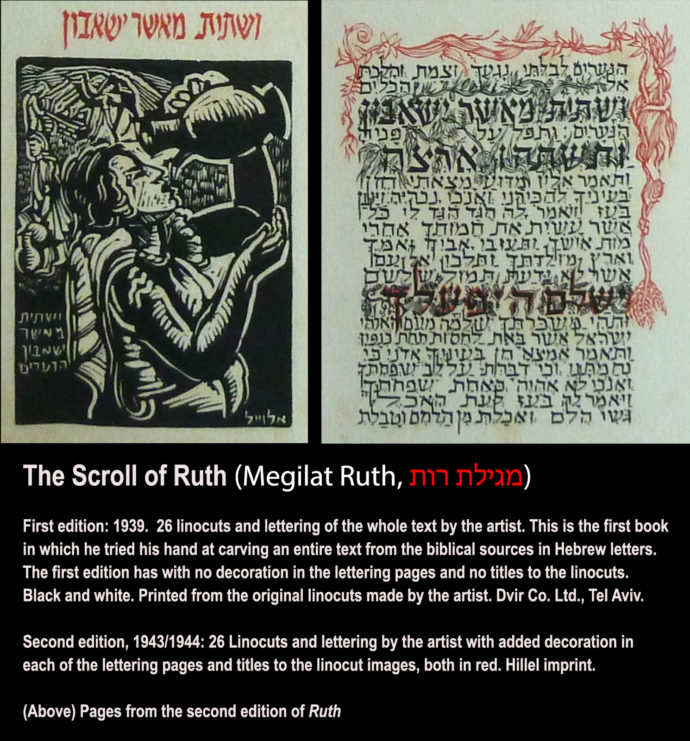

Now this word “megillah” that Allweil used fooled me. In her book, Galia Bar Or named Allweil’s works as The Book of Ruth, The Book of Esther and The Book of Lamentations. However, in her book Galia Gavish called them the Scroll of Ruth, the Scroll of Esther and the Scroll of Lamentations. I wondered: Did Gavish literally mean scroll like a Torah and not a codex (what we would call a book)? Did he first publish those titles as scrolls and later as codexes/books? Fortunately Ruth Sperling settled the question. In an email she wrote:

“As to your questions about the scrolls. The biblical books that my father created were all published as books with covers and several with decorated envelopes. The Biblical books of Ruth, Esther and Lamentation are termed in Hebrew Megilat Ruth, Megilat Esther and Megilat Eicha (Megila = scroll; Megilat = the scroll of; Eicha is the Hebrew name of Lamentation).

I’ll end his biography here. Since I’m concentrating of Allweil’s graphic works, I’ve glossed over his accomplishments and struggles as a painter in oils. But that was a huge part of his oeuvre. Bar Or devotes much of her book to Allweil as a painter, and her book can be read online. Here’s the link. And for more of Arieh Allweil life and accomplishments, please go to his page at the Israel Museum’s Information Center for Israeli Art at: https://museum.imj.org.il/artcenter/newsite/en/?artist=Allweil,%20Arieh

From Allweil books: (L to R) the title pages for “The Scroll of Lamentations,” the envelop for “The Scroll of Ruth” and cover of the 1948 “Chapters for Passover Celebrations.”

Allweil’s books

This section features a list of Allweil’s books–1939 to 1949–as provided by his daughter Ruth Sperling. She gave dates for each edition. But first I want to emphasize the importance of these works by again turning to Galia Bar Or in her book Arieh Allweil: Letters, Figures, Landscapes. She wrote:

“In the years between the beginning and the end of the Second World War (1939–1945), Allweil completed a series of books of linocuts that he drew and wrote, in which he conducted a personal dialogue with layers of illustrative and writing culture and of Jewish history. The series consisted of five books, among them the biblical books of Amos and Lamentations, which are perhaps the hardest and most acerbic of his works. In these linocuts Allweil carved not only the pictures but also the letters, which he designed and drew one by one. He printed each of the books himself, manually, in editions of 100 copies, bound the pages into books and signed them with the logo of the independent publishing firm he founded and named after his father: Hillel Publishers. At a later stage he also published printed editions of a handwritten and illustrated Passover Haggadah, and devoted his time to printmaking.”

She also wrote: “Shock at the war’s horrors and deep lamentation reverberate through Allweil’s work, first in The Book of Amos from 1940, then The Scroll of Lamentations which he completed in 1943, and The Scroll of Ruth, which he worked on for several years and completed in 1944.”

The original linocut block (left) for Chapter 3 heading of Allweil’s “Book of Lamentations” with the printed page opposite. (Photo of the block courtesy of Ruth Sperling and Nava Rosenfeld.)

While my attraction to Allweil was in his images, a few words are needed to highlight his efforts as a Hebrew font designer.

As quoted above, Bar Or said, “Allweil carved not only the pictures but also the letters, which he designed and drew one by one.” Yet Allweil in the colophon to Amos wrote: “Book of Amos printed with the original plates of linocuts made by the painter and facsimiles of his writing.” That seems to be a contradiction so I asked Sperling about it.

In an email she wrote: “The word ‘facsimiles’ is actually written in Hebrew just with Hebrew letters: פקסימיליות. This was 1940 [when Amos was first published]. Now, the lettering was not all carved in linoleum. I think the pages with large letters were. The pages with smaller letter text I think were written by pen. He had different sizes and shapes of pens. Some I still have. He used to buy the ink for that from a person who was writing the Tora scrolls, in Hebrew termed “Sofer Stam.” The large letters were carved in linoleum and were written carved as mirror images of the final pages.” As an example, She provided the image of the original linoleum block used to begin Chapter 3 in The Book of Lamentations.

Looking at my copy of Amos, I now can see that pages with only large lettering were created with linoleum cuts, and pages with only small lettering were first written with a pen then photographed to make metal plates. For pages with full-page illustrations, both the image and the caption were cut into linoleum (although perhaps two separate blocks–see the images that begin this post). Furthermore, I suspect, for pages like this chapter page from Amos the historiated initial with was cut into linoleum while the text originally was written with a pen.

Galia Gavish in her book Arieh Allweil: Prints & Caligraphy, Books 1939-1949 remarked: “The Scroll of Ruth was written using a square letter where the tall letters such as “ל” integrate into the lines above, and the letters that descend, such as “ך”, integrate into the line below.” Those letters that ascend above or descend below the line can also be seen from this page from Amos. And in an email, she added, “When Allweil thought as calligrapher he was thinking about the soul of the letters. [He believed] one has to give the right space so each letter will relate to the placement and the subject of the text. He considered the text and the illustrations having the same importance.”

Max Brod in his essay in the book Allweil, commented on the artist’s redesigned Hebrew font: “He has devoted much time to a new styling of the Hebrew letter; and here as well he continues the old tradition of our Haggadah writers and woodcut masters, in whose fine and ever fresh shapes our letters found their source of their inspiration. The human figures of these Haggadot are like Alefs and Shins [Hebrew letters] that have come to life. The same magic touch appears in Allweil’s illustrated books of Ruth, Lamentations, Esther, Amos, etc. He has written all these by hand in letters that are formed by a modern rhythm, and has ornamented them with linoleum cuts that are full of fantasy.

In 1955 he won the Touroff Prize for his bible illustrations. In an email Sperling said the prize “was named after Dr. Nisson Touroff. The Touroff Annual Memorial Prize was awarded for works in the Hebrew Language in the fields of psychology, education or art. Dr. Touroff, scholar, writer and educator, was dean of the Hebrew Teachers College in Boston for many years. The fund was established by Edmond M. Melton, an American philanthropist.”

Here is an illustrated list of Arieh Allweil’s books with publication history was provide by his daughters Ruth Sperling and Nava Rossenfeld. The Hebrew names in read are in her father’s font.

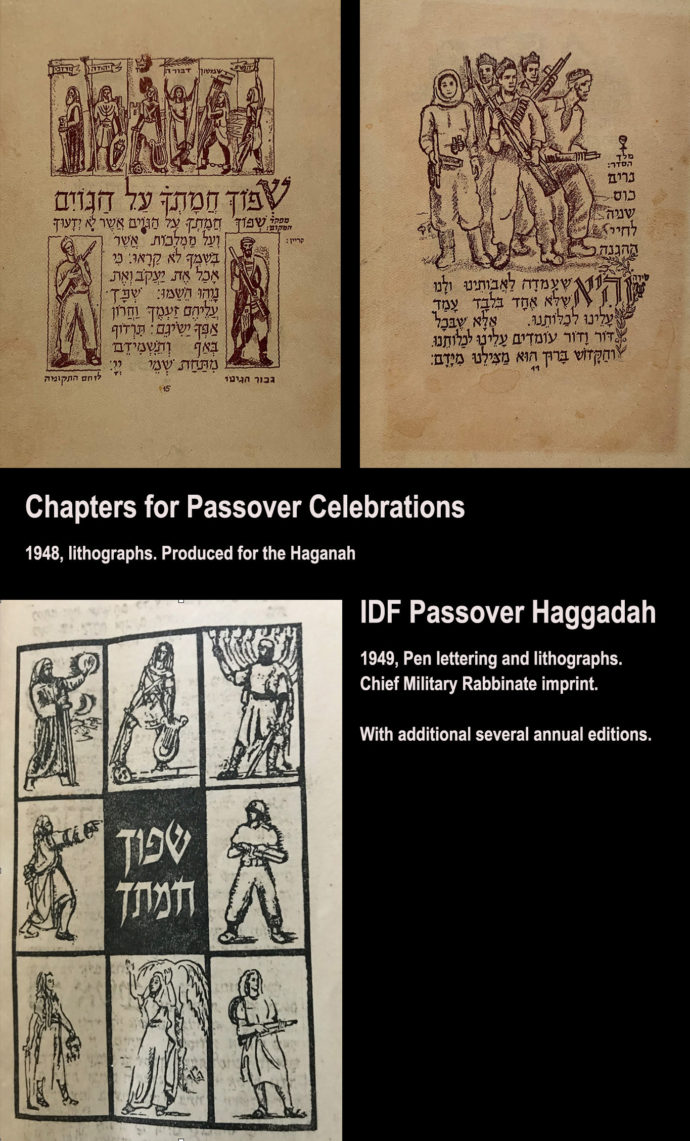

In the box directly above are two Allweil publications directed toward the observation of Passover. Galia Bar Or in her book Arieh Allweil: Letters, Figures, Landscapes wrote: “His memories of Bobroysk [his home village in Galicia] also surface in the Chapters for Passover Celebrations that he created in 1948 for the Haganah, and in the Passover Haggadah that he hand-copied and illustrated for the IDF the following year. In both of these Allweil integrated old with new: prints from books he had created in previous years, and drawings that he created especially for the Haggadah.

The Haganah was the main Jewish paramilitary organization in Palestine between 1920 and 1948. After Israel independence it became the core of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF).

Future Allweil posts

I plan on presenting online for the first time all of the images for Arieh Allweil prints that he made for Tura Afura (lithographs) and Touring, Ruth, Amos, Esther, Anonymous Jew and Lamentations (linocuts) with translations of image captions and some of the text plus commentary. I’ll start with Amos, the Allweil book that first piqued my interest in the artist. Iddo Gal, Associate Professor in the Department of Human Services at the University of Haifa, has already done an exemplary jobs translating Allweil’s Amos.

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/introducing-arieh-allweil/trackback/