Willard Clark: Kevin Ryan’s Grandpa

This article in a slightly abridged form was first printed in the spring 2011 edition of the Newsletter of the Print, Drawing & Photograph Society of the Baltimore Museum of Art. (All photos are mine except that of Willard Clark.)

An April, 2011, week in Sante Fe with my three sisters was full of discoveries: the rugged high desert landscape, aromatic Mexican-inspired cuisine, handsomely painted and almost irresistible Pueblo pottery, and, when I set out on my own to avoid entering yet another jewelry store with my sisters, a story of a woodcut artist and his devoted grandson.

The latter discovery began in a used book store a few blocks from Sante Fe’s central plaza. A few framed color woodcuts hung around a doorway. They depicted a romantic and somewhat paternalistic view of the sleepy world of adobe homes, Spanish missions, burros, shawl-covered women, sombrero-wearing men. The shop owner told me about this remarkable man who arrived in Sante Fe in the 1920s, was an artist and commercial printer until 1942, worked as a machinist for 30 years, then upon retirement returned to printmaking. But the impressions for sale were all printed by the artist’s grandson. Then the book dealer gave me the grandson’s phone number.

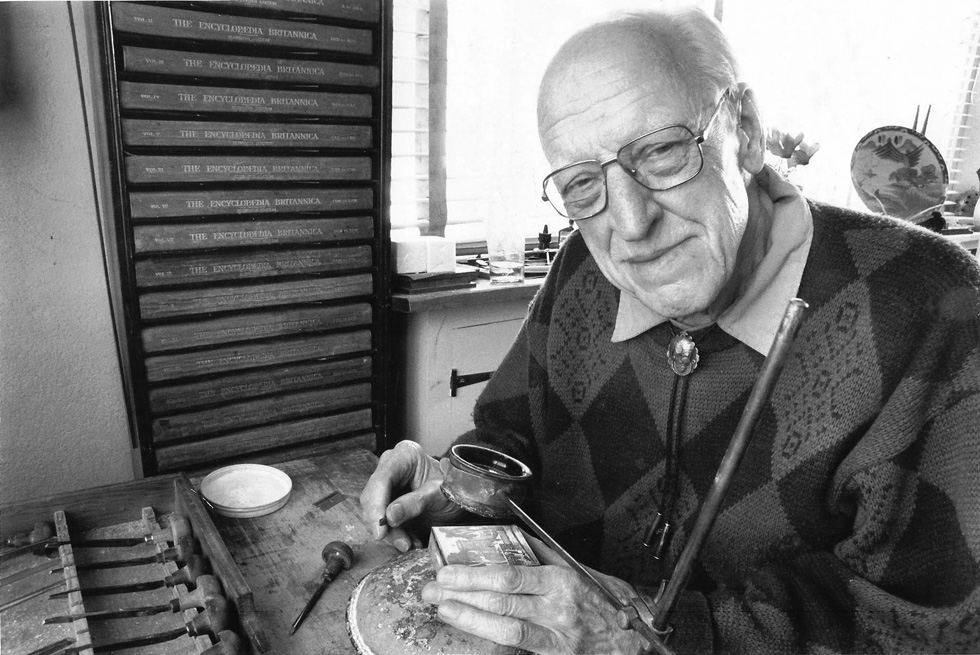

Willard Clark (Photograph by William Clark, no relation)

So this is the story of Willard Clark (1910–1992) and his grandson, Kevin Ryan. And Kevin will do the telling. But first a little background on Willard Clark before the years his grandson describes. This information is culled from the book Willard Clark: Printer & Printmaker by David Farmer (Sante Fe, NM, Museum of New Mexico Press, 2008, the expanded edition). Willard was born in Massachusetts but raised in Argentina, where his father was a General Motors executive. Trained as an artist and illustrator in New York, Provincetown, and Indianapolis, Willard was on the way to California in 1928 when he stopped in Sante Fe to visit a family friend. He was immediately taken by the Spanish culture there. It reminded him of his years in South America.

Finding that Sante Fe was without a full-service commercial print shop, he bought a small press, taught himself how to use it, and within a year of his arrival in town opened for business. Not only did he set the type for his various commercial jobs, but he made woodcuts, many in color, to illustrate the work. According to Farmer: “Willard Clark created a unique typographical style and a method of rendering illustrated job printing that became closely identified with the community.” He married, had two daughters and built an adobe home with a shop on the first floor, living quarters above. His business, Clark’s Studio, survived the Depression years. He even printed a book for the well-known woodcut artist Gustave Baumann. But whether from growing competition or a need for steadier income, Willard closed the press in 1942, sold his printing equipment, carefully wrapped up and stored away his handmade wood-cutting tools, hundreds of woodblocks, and finished prints. He took a job at the Los Alamos National Laboratory as a tool and dye specialist. He retired 32 years later.

Fortunately in the early 1980s Pamela Smith from the Print Shop of the Palace of the Governors in Sante Fe remembered Willard’s accomplishments before the war, visited often and encouraged him to resume making art. Some of his most accomplished woodcuts come from the last decade of his life.

So after trading phone messages I finally visit Kevin Ryan on my last day in Sante Fe. We meet in front of a small garage, across the street from the house his grandfather built. Inside, the space is divided up. The front room has framed prints covering the walls and a small press to one side. The smaller back room is very special. Its shelves hold envelopes of unframed prints and stacks of neatly tied sets of woodblocks. The number of blocks in each set varied according to the number of colors in a given print.

Kevin agrees to be interviewed by mail about his years working for his grandfather. So I mail him a set of questions, but instead of answering them one after the other, he sends back a 10-page, hand-written essay that is very tender and very revealing about how one generation can profoundly affect another in the best of ways. This is Kevin’s story.

Photocopies of the 10-page manuscript written by Kevin Ryan

Remembrances with my Grandpa

By Kevin Ryan

I remember when I was just eight years old sitting in his living room, watching him draw a portrait, becoming very fascinated, and wanting him to show me how to draw a face. That is when I started drawing, and I always enjoyed getting a lesson from him.

When I was about 12 years old, he started a gallery on Canyon Road with my mother and stepfather. He was working in Los Alamos at the lab as a machinist. I think he missed being an artist. He started painting landscapes, and I remember going with him to the mountains a few times and watching him paint. He continued working in Los Alamos and painting on weekends until his retirement, when he took over the gallery and started making custom jewelry also.

In 1975, I was 22 years old when he asked me to come work in the gallery and learn to run the business and make jewelry. I worked for him for a year, made jewelry, and learned how talented he was. On Mondays I would do lost-wax casting in a little room that used to be a photography darkroom in the 1950s. This is where I discovered his woodblocks and some of the commercial printing from the 1930s. I was completely surprised. He never talked about or showed anybody the work from this period. He was a very quiet, humble, and hard-working man.

I went on to do construction, carpentry, plastering, and house painting. Grandpa concentrated on making beautiful custom silver and gold jewelry, and taking care of my grandmother, Bertha, who was very sick with cancer. She died around 1980, and he closed the gallery but continued to make jewelry. I moved into the house across the street from his in 1983, when my son was born. I would go over on weekends to visit and help him with house repairs.

In 1985 Pamela Smith from the Palace of the Governors started coming to his house to talk about letterpress printing. They became good friends. That is when he decided to buy a 1910 Potter Proof Press. He was very excited to get out the old woodblocks, and he started doing some new ones. He had to make some modifications to the press, like spring-loaded clamps to hold down the paper in registration and a way to cover the cylinder to even out the pressure on the woodblock.

It wasn’t until around 1990 that he asked me to come over on Saturdays so he could teach me about the different phases of printing and making woodblocks. I took down notes, listened, and asked questions. In May of 1992 Grandpa had a stroke and got back home in June. He didn’t have full control of his right hand. That is when he asked me to help him with his book, Recuerdos de Sante Fe, 1928–1943. [It’s about his early years in Sante Fe, done in 46 vignettes, each illustrated with a wood engraving.] He had started it in 1988 and by 1992 had finished 50 of the 100 in the limited edition. I continued doing construction in the mornings, and he would pay me to print in the afternoons. The first day I found out how to cut paper for the text pages. (He had already finished all the prints.) I figured it was around 2,800 pieces of paper and it was going to take a while. Luckily I got to break it up by finishing the printing of his five-color Sanctuario de Chimayo woodcut, for which he had a list of about 25 people waiting.

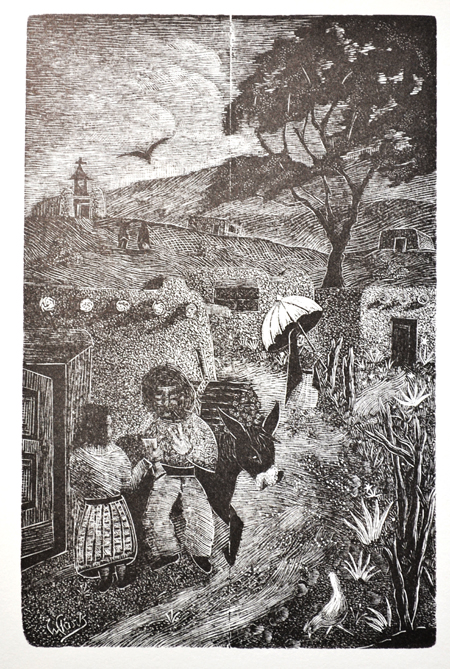

< The Wood Merchant, wood engraving by Willard Clark, 1988, an illustration for Recuerdos de Sante Fe, 1928–1943. This print was also included in Endgrain: Contemporary Wood Engraving in North America, Barbarian Press, 1994.

Grandpa was pretty much bedridden, but his bed was just in the next room. The first printing I did was the Chimayo print’s orange color, which had to go over the black he had printed first. I mixed the color with dry pigments and linseed oil on a litho stone he had from the 1930s. He had no formulas for mixing. But he did say that each time he made a new edition he didn’t try to match the color exactly, but will try to improve it or let the slightly different first color make subtle changes to the other colors. He did give me some tips on how he mixed his colors. Like he always added the opposite color and a little black to tone down the color, and sometimes he added a little of the previous color or colors. Also if you wanted the color to be more transparent, he said to add less white and roll it on the block thinner.

I wasn’t sure what the third color was; so I asked him. He said for me to figure it out, and I did it. This helped me to understand and appreciate how one plans and executes a multi-color woodcut. After finishing the print, I began the text pages of the book. Each of these 2,800 pages had to go through the press three times. After finishing a few pages I realized how much work it was. He wanted each page to be almost perfect.

Framed restrike of a woodcut of Willard Clark called Clouds and the three blocks used to print it

Grandpa after a few months was starting to feel better and was working on the wood engravings for his second book, The Simple Life. Before his stroke he had finished the 12 beautiful shaded pencil drawings of life in a small northern New Mexico village. The press, his desk, and the drafting table for doing the engravings were all in the same little room that used to be the office for the print shop in the 1930s. While I was printing, he would be engraving right next to me. When he took a break, he would talk about the different techniques and how he would try to capture the shading and tone of the pencil drawings. We would look at other wood engravers’ work or talk about printing or the next project.

He wanted me to start doing my own blocks, which I could work at in the evenings. So we ordered my own engraving tools because he didn’t like anyone using his tools, which he made himself. I also decided to make my own woodblocks from a very large piece of walnut I had. He also showed me how to make a circular, leather, sand-filled pad to rest and spin the block on. Then he showed me how to transfer the drawing to the block. I started engraving, and I found I really enjoyed it. It was like making jewelry, working in a small, detailed, exacting way. I finished the engraving, showed it to him and could not wait to print it and hear what he thought of it. On a long adobe wall in my engraving I used a technique to try to get the finest, thinnest, closest-together lines, which was very time consuming. I could tell he was very impressed. The following week I saw he was using the same technique in one of his engravings of an adobe wall. It felt good to be working and spending time with him again.

Soon after this we found out the New Mexico Museum of Art was going to have a show of Grandpa’s prints in 1992. He was very excited and energized by the unexpected attention. More and more people were calling and coming over to see his prints and talk to him. The opening for the show was very nice, and lots of people and old friends showed up. So many people called to make appointments to come see the portfolio of new and old prints that he had to turn some of them down. He was making around three appointments a week. A group would usually come after lunch and stay several hours, looking through 180 prints and the book. I could tell Grandpa enjoyed answering their questions and telling stories about the old days in Sante Fe.

Between 1985 and 1988 Grandpa had concentrated on printing a portfolio of all his woodblocks and making around a dozen new ones. He was doing small editions of 15 to 30. When we started running out of some of the prints, I started printing them and he would sign them after passing his inspection. On the back of each print he would put a label with which edition, how many, catalogue number, type of wood, what year the woodblock was made, when it was printed, and what ink was hand-ground.

From the summer of 1992 until October we worked everyday, except a little on Sunday. I did notice he was getting tired easier, needed to take longer naps, and he started seeing fewer people. He did accept a few jobs, like illustrations for a Christmas in Sante Fe book. For this job he asked me to come up with six small scratchboard illustrations. I would do a drawing, and he would tell me what he thought and give a few suggestions. I was always amazed by his talent at composing such beautiful illustrations. He started talking about taking more commercial art printing jobs and it could be more like the old days. People still needed that kind of work, he thought.

He wanted me to continue working on my own artwork. I loved working with him for he always seemed to inspire me. I was excited about the future. Yet I noticed he was starting to get tired a lot quicker, didn’t want to meet people, and only worked for maybe an hour on engraving the new book. Finally one day he said that he didn’t want me to know until then that he had a tumor in his chest, and he wished we would have more time together. He asked if I could try to keep Clark’s Gallery & Studio in business and do restrikes of his prints. Because of all the renewed interest, it might be enough to keep it going. He wanted me to finish the Recuerdos de Sante Fe book and start setting type, using the same typeface, for The Simple Life book. By the middle of November he had finished 4 of the 12 engravings for the new book. He would try some days to do a little work but was often too tired.

At this time my Aunt Bertha, my mother’s sister, came from Nebraska to visit. Grandpa asked to have a meeting with us all about Clark’s Gallery & Studio. He said he wanted them to help me with some seed money so I could finish the Recuerdos book, sell the original prints, and do restrikes. We agreed that in return I would pay a royalty to them of 20 percent for each of their originals and books, and 10 percent for any restrikes. That seed money would pay rent, utilities, insurance for the studio space. He hoped that my mother would keep the house and that I could help remodel, fix it up, and keep the studio part of the house as Clark’s Gallery & Studio. We all agreed. I felt excited about the

idea that I could make a living being a printer and artist and be able to get Grandpa’s artwork out into the public.

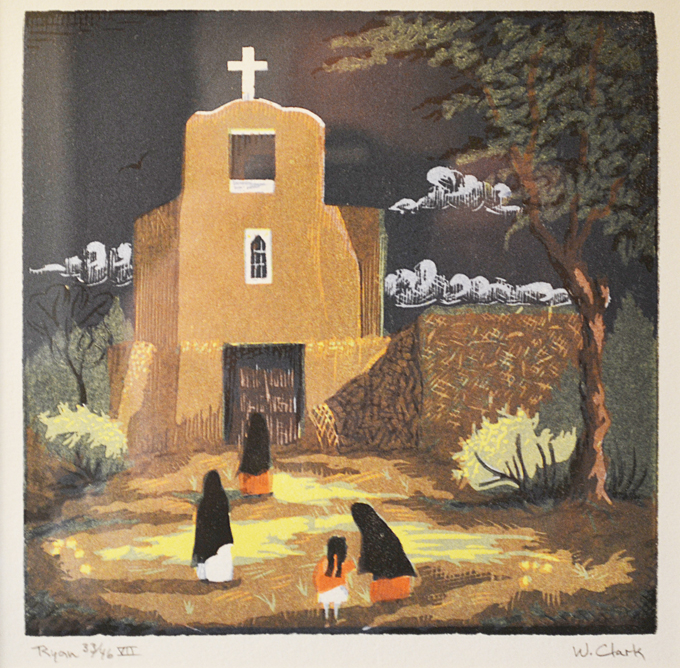

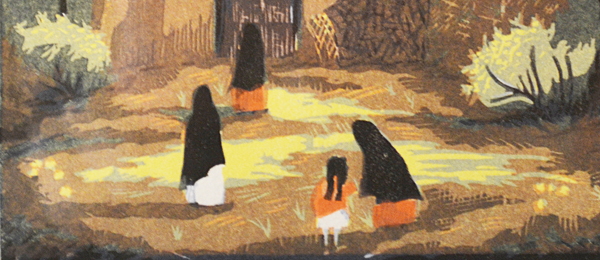

San Miguel Church, restrike of a five-color woodcut on basswood, 1985, by Willard Clark

But watching Grandpa’s health quickly deteriorate left me feeling very sad. I tried over the next few weeks until his death to be there all the time for whatever he needed, but he still wanted me to keep working on the book to finish it.

The day he passed away he told me not to call anybody. He said he already had said his good-byes. He just wanted me to be there with him. As he was passing over to the other side, I felt such a strong connection and love for him, I cried for the first time in many years. I made a promise to him and myself to be a better person. It was one of those moments in life that you know is transforming.

The next year I spent going through all his stuff and fixing up his house. My mother bought her sister’s share of the house and decided to divide it—rent the house and let me keep working in the studio part. That lasted from 1994 to 1999, when I moved everything across the street to my old garage, on which I had to do a lot of work.

The first year was a struggle to make it, but enough people were showing interest in the originals. And I was selling the Recuerdos books as they were being completed. I saw that the original prints would sell out pretty fast, so I got an art dealer that Grandpa knew to help me set the prices and set up a plan to market them. About half of the 180 prints would sell well, and the editions were not that big.

Then the Museum of Art asked me to include about eight restrikes in their Christmas catalogue. They sold well. So I was asked to put a dozen restrikes into the museum shop. The lady who ran the shop admired him and sold restrikes by telling customers about Grandpa and the prints’ history. At the same time she was also selling Gustav Baumann prints, and the restrikes of Grandpa’s prints were a lot cheaper. I had tried to make them affordable. There was a big-time art dealer and gallery owner at the time who wanted me to turn over all the original prints and woodblocks for him to sell, like he had done for Gustav Baumann. I told him I wanted to print and sell restrikes and would never sell the woodblocks. He thought I was making a big mistake. With the museum shop with the best location in Sante Fe selling restrikes, I knew they would sell. One of the biggest galleries in town asked to do a Christmas show of originals and then keep some on consignment year round. Now with the originals and restrikes selling and other things popping up—like David Farmer’s book about Grandpa, Willard Clark: Printer & Printmaker—Clark’s Gallery & Studio was making it.

I will be forever grateful for what Grandpa left me—for the time we spent together, the knowledge and wisdom he tried to impart to me.

Kevin Ryan in Clark’s Gallery & Studio with a wall of framed restrikes of Willard Clark woodcuts.

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/kevin-ryans-grandpa/trackback/

Thanks for sharing this beautiful story.

Joan Sills

I love Clarks work and own one of his bracelets. A treasure

I have a painting called Changing Waters and just love it!

I’ve purchase a few black prints from the museum store and was given some copies of menus that Willard made for La Fonda. I love woodblocks would like to add more to my dining room. The small vignettes are my favorite-I look at them whenever I am in the museum.