American Jewish Artists: Pre-1947

Introduction

After devoting a blog post on Die Bibel by Bruno Goldschmitt, a Nazi party member (albeit he created that work a good 10 years before he joined the National Socialist German Workers’ Party), I’ll let the pendulum swing full the other way with this post. (Link to Die Bibel post.)

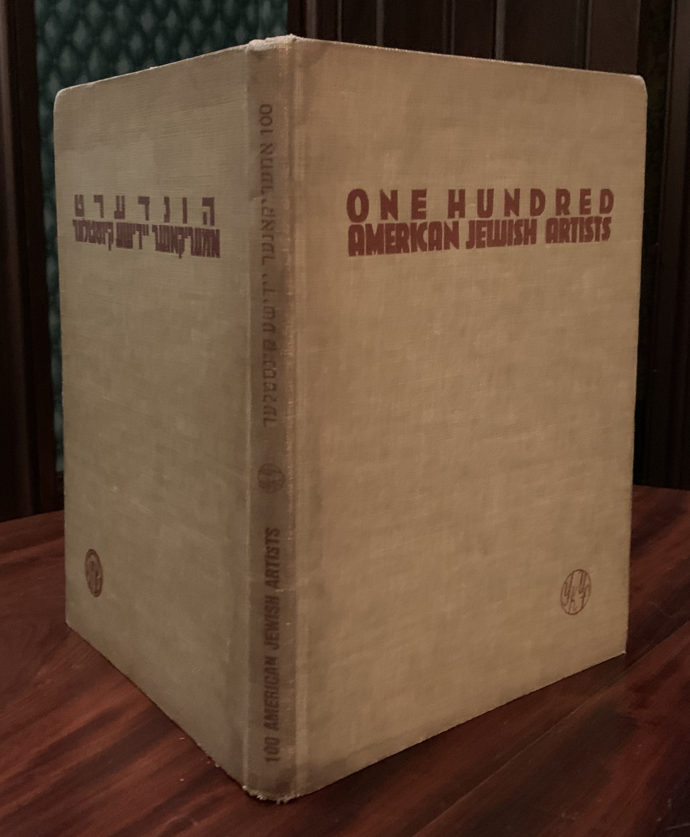

I recently purchased a copy of One Hundred Contemporary American Jewish Artists: Painters and Sculptors (YKUF Art Section, New York) with an essay by Louis Lozowick. Fittingly it was published in 1947, soon after the extent of the Holocaust horrors were fully known. YKUF stands for Yiddisher Kultur Farband, a U.S. association founded in 1937 to preserve and develop Yiddish culture in Yiddish and English.

Preceding Lozowick’s essay, the following statement was printed: “The artists are represented in this book in alphabetical order. Their names were chosen by an Editorial Committee consisting of seven artist-members of the YKUF who alone are responsible for all matters pertaining to the publication of the volume. The Committee is keenly conscious of the artists unavoidably absent from the book but hopes to remedy this circumstance in large part by the publication of another volume.” I’ve found no evidence of a second volume. Nor can I find out who besides Lozowick (I assume) was on the committee.

The book’s spine has the title in Yiddish and English. If you open the book with spine on the left, then the Lozowick essay is in English. If you open the book up with the spine on the right, the essay is in Yiddish. To see the alphabetical presentation of the 100 artists requires opening the book up on the English side.

While the title mentions artists who were painters and sculptors, a number of them were also printmakers. It so happens that I have prints by 10 of the 100. (Lozowick is not among the 10 even though he was an excellent lithographer.) In his essay Lozowick names three other Jewish American artists who are not among the chosen 100 but by whom I also have prints. And after doing an online biography search on printmakers in my collection, I’ve confirmed that I have prints by another 16 Jewish American printmakers active before the book was published.

In this ART I SEE post, I’ll first pull some quotes from Lozowick’s essay and present prints by the three artists mentioned in the essay but were not among the chosen 100. Then I’ll display the two-page spreads on the 10 artists by whom I do have prints along with one print from my collection by those 10. Finally, I’ll show a print by each of the 16 Jewish artists in my collection but not named in the book.

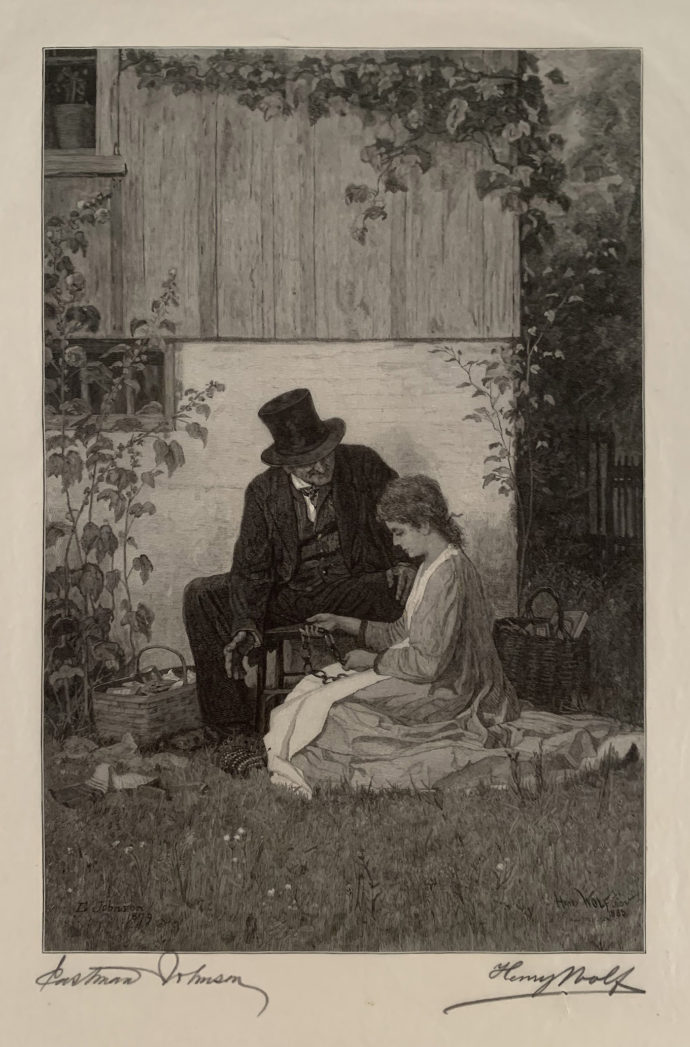

Henry Wolf (1852-1916), “The New England Peddler,” wood engraving, 1884, 10 7/8″ x 7″. (Countersigned by the painter Eastman Johnson. It was Johnson’s 1879 painting that Wolf made his wood engraving from.)

Lozowick’s Essay

To my surprise Louis Lozowick (Russian-born 1892-1973) began his essay–”The Jew in American Plastic Art”–with the colonial period. I had assumed he would stick to the 20th century. Certainly all of the chosen 100 were active in the 20th century, and 96 of them were alive when the book was published.

In the colonial period, Lozowick named no Jewish artists: “In the Colonial and early Republic years it [Jewish contribution to the arts] took the form of patronage, of liberal commissions for portraits distributed among the fashionable non-Jewish artists of the day.” He added: “There are portraits of Colonial Jews painted anonymously in the naive, unpretentious manner of the folk artists. Were any of them Jews? We do not know….”

In the 19th century Lozowick lists some 20 Jewish American artists including Theodore Sidney Moïse (1806-1883), who served in the Confederate Army; Max Rosenthal (1833-1918), who served as an artist attached to the Union Army but was best known for introducing chromo-lithography to the U.S.; and Moses Jacob Ezekiel (1844-1917), who sculpted monuments to Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson.

Among those 19th-century American Jewish artists was Henry Wolf (1852-1916). The above image first appeared in my ART I SEE blog in a 2013 post called “New School Wood Engravers: Forgotten 19th-century Celebrities.” (LINK) It never occurred to me at the time that Wolf was Jewish. Lozowick wrote that Wolf “became nationally known for his expert reproductions of the world’s masterpieces by the process of wood engraving. Ultimately when photography became dominant as the medium of reproduction, these wood engravings, done with the most extraordinary meticulousness, came to be appreciated in their own right.”

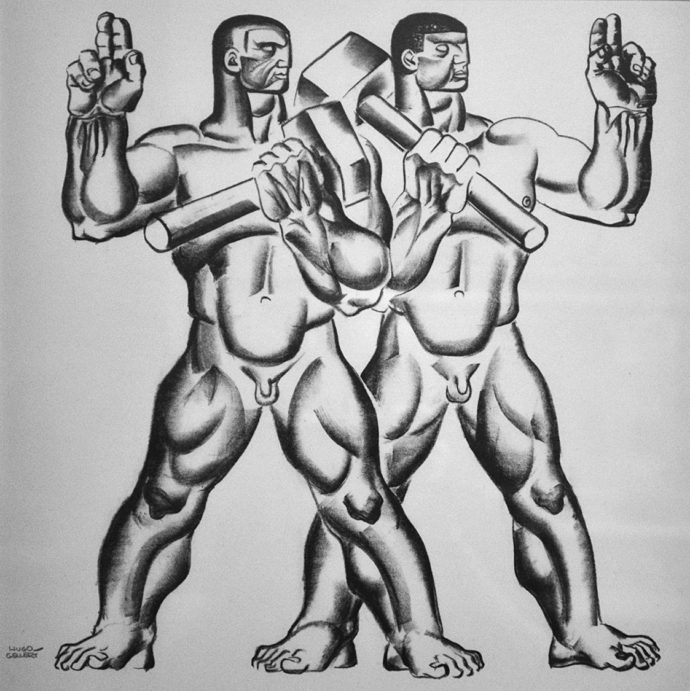

Hugo Gellert (Hungary born 1892-1985, “Primary Accumulation 11,” lithograph, 14 1/4″ x 13.” (From the portfolio of 60 lithographs by Hugo Gellert, with accompanying text, “Karl Marx’ Capital in Pictures,” printed by E. Desjobert, Paris, France in 1933. )

As expected, the bulk of Lozowick’s essay is devoted to the 20th century. “By the turn of the twentieth century,” he wrote, “Jewish participation in art reaches such proportions that qualitatively American art would be a different and poorer thing without it; quantitatively–the mere listing of names would require more space than the entire Introduction. Jewish artists play a significant, often a major role in some schools and tendencies. All that can be attempted here is to indicate the leading trends and cite some names identified with them.”

Hugo Gellert, whose lithograph Primary Accumulation 11 is shown above, is named in the section about artists and socialism. While not all socialist artists were Jewish, Lozowick wrote, “Jewish artists played an influential part of it. These artists have been variously designated as ‘class struggle,’ or ‘proleterian,’ or most often ‘social’ artists. Strictly speaking, they do not constitute a school but a trend, for their common basis is ideological not stylistic.”

Lozowick went on to mention Post-Impressionism, which he said “comprises several distinct currents: Cubism. Expressionism, Surrealism, etc. In Europe they represent organized artists with clearly defined esthetic principles. In America they are practiced by individual artists, not always with entire consistency.”

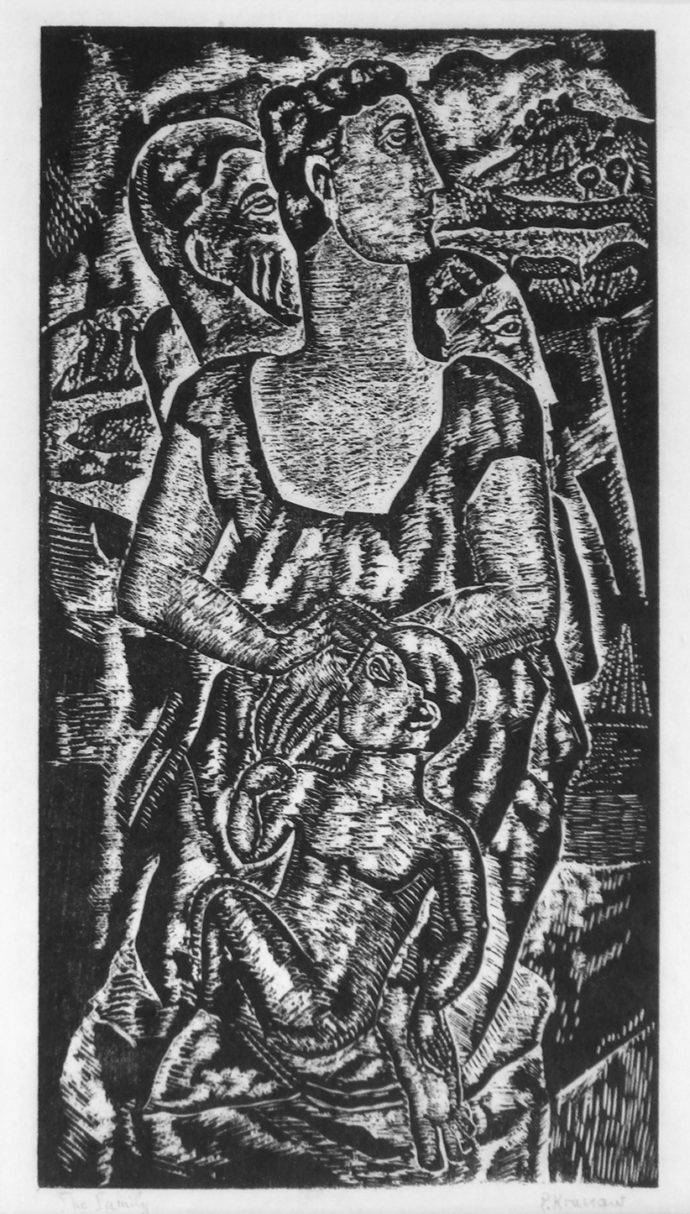

Peter Krasnow is not mentioned until a section on “many artists who either fall within classifications already mentioned or fall into too many of them.” I think of Krasnow as mostly a sculptor. In the Smithsonian American Art Museum online listing for Krasnow (LINK), it states: “In 1934, after a three-year stay in France, he spent the next decade carving abstract wood sculptures.” His linocut (to the left) predated his French sojourn, but his mark-making somehow anticipated his days cutting into wood. I can imagine it as a low relief. Lozowick didn’t include his name in a section on sculptors.

In his conclusion Lozowick wrote: “The twentieth century has been crowded with enormous and eventful changes in the destiny of the Jewish people. The slow and difficult reconstruction of Palestine [Israel would not become independent until 1948], the flowering of a new life in the Soviet Union [some two million Jews would flee the Soviet Union after 1970], the phenomenal growth of the Jewish community in the United States, the harrowing extermination of millions in the murder camps of the Nazi cannibals–these have been some of the more striking manifestations of a profound historic process. The Jewish artists, wherever they were, could no more escape the impact of these events than any other section of the Jewish people. But their reaction was in most cases spontaneous and personal rather than the consequence of a clearly organized movement….

“In recent years the Nazi pestilence drove to our shores some of the greatest artists not only among the Jews but also in the world. Distinguished painters of the older schools, like Eugen Spiro, Max Oppenheimer (MOPP), Artur Szyk and representatives of more recent trends like Jacques Lipchitz, Marc Chagall, Moise Kisling, have joined our family. Whether their stay here is temporary or permanent we welcome them.”

10 of the Chosen 100

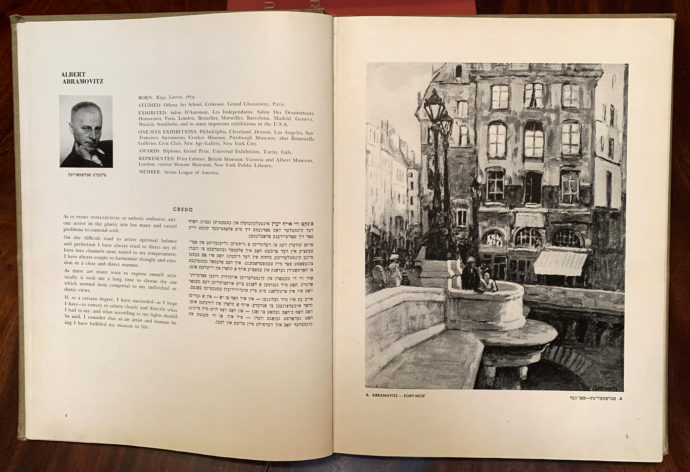

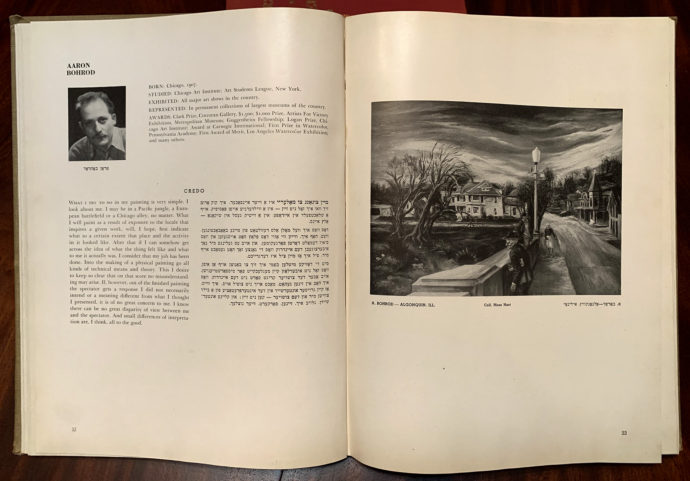

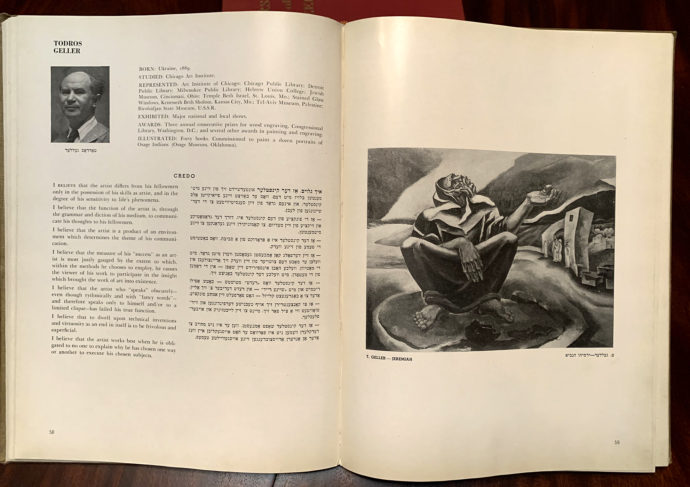

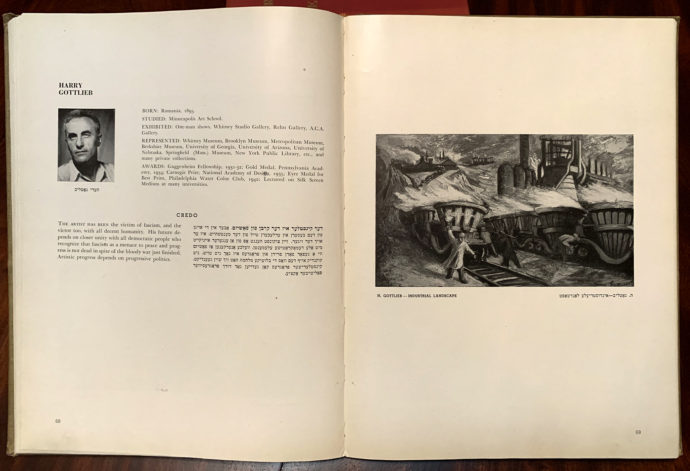

As stated earlier, I have prints by 10 of the 100 artists chosen for a two-page spread for the book One Hundred Contemporary American Jewish Artists. On the left-hand page of each spread is a headshot of the artist, brief bio information, then a credo in English and Hebrew. An artwork of the artist, usually a painting, appears on the other page. For each of the 10 I present their page spread followed by one print of theirs in my collection.

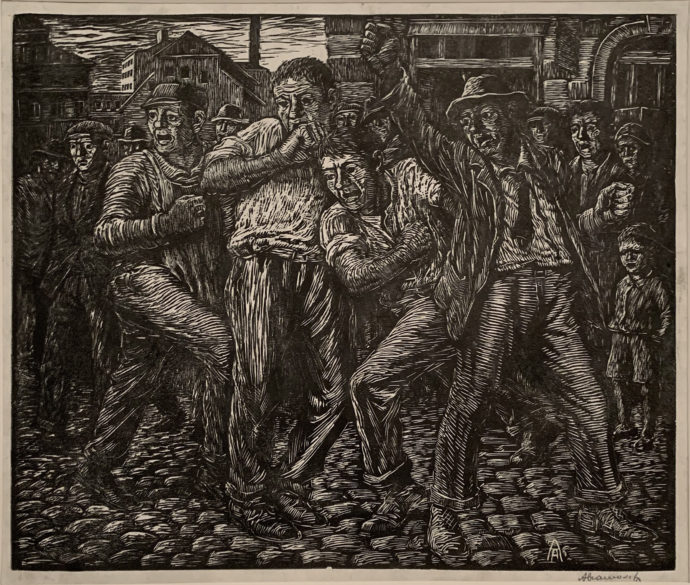

Albert Abramovitz

This Abramovitz–Strike, linocut, 1932, 9 5/8″ x 12″–is the most recent of the five of his linocuts to enter my collection. I passed on it by the first time I saw it some 20 years ago, soon regretted it, soon after found it rather unaffordable, and finally this year snapped up this copy on eBay. Born in Riga, Latvia in 1879, Abramovitz died in East Meadow, NY, in 1963.

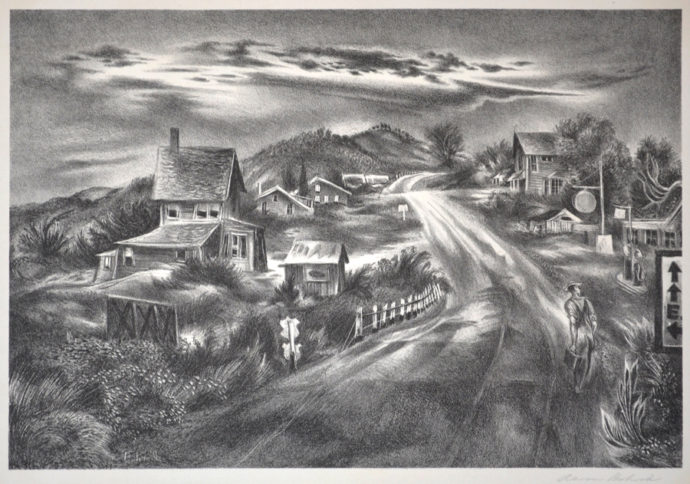

Aaron Bohrod

It’s interesting that this lithograph by Bohrod (1907-1992) shares the compositional structure with the painting in his two-page spread in the book. Pennsylvania Highway, 1944, 9 1/8″ x 13 1/2″, was published by the American Artists Association in an edition of 250. Albert Reese in his book American Prize Prints of the 20th Century (American Artist Group, New York, 1949) includes this print for being “Selected for Fifty Prints of the Year, 1944.”

Todros Geller

This woodcut–Yiddle mit’n Fiddle, Berl mit’n Bass, 1926, 10″ x 8″–by Geller (1889-1949) was printed on Japanese wood veneer paper, laid down on ivory laid paper. It was the seventh woodcut in his Yiddish Motifs, a portfolio of seven woodcuts published by L. M. Stein, Chicago, in an edition of 150. The portfolio was also covered in the same wood veneer paper. When L. M. Stein published a book–From Land to Land–with reproductions of Geller woodcuts in 1937, it used the same veneer paper on the cover. My copy of Yiddle was purchased on eBay from a seller in Poland.

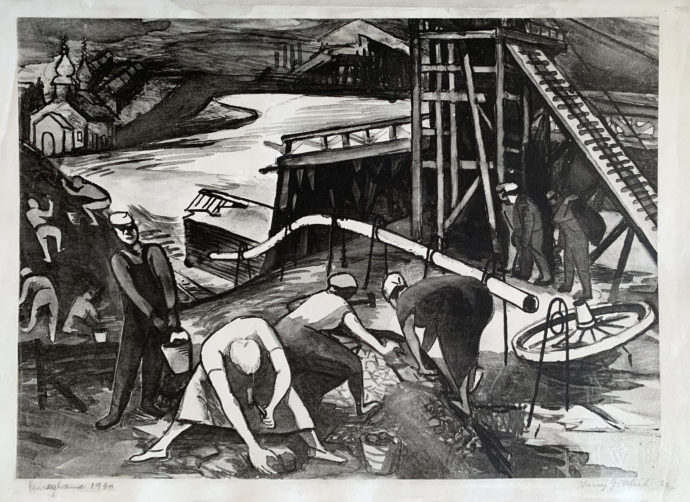

Harry Gottlieb

This Gottlieb lithograph–The Coal Pickers, 1936, 10″ x 13 3/4″, edition maybe 30–was included in “America Today,” an art exhibition organized by the American Artists’ Congress. The exhibition was held simultaneously in 30 American cities in 1936. An exhibition catalogue–America Today: a Book of 100 Prints–was published by Equinox Cooperative Press, New York, 1936. This Gottlieb print is plate #54 in the book. Somehow Gottlieb (1895-1992) trimmed the image down from a litho that originally measured 12″ x 15 7/8″. I discussed this transition in an August 2020 blog post: “Harry Gottlieb’s ‘Coal Pickers.’ ” (LINK)

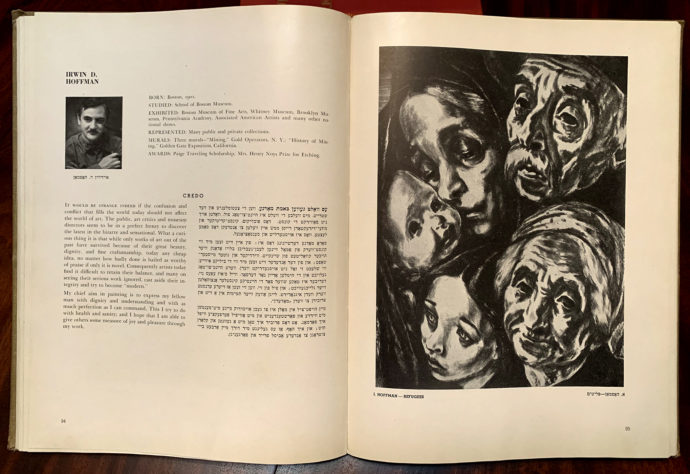

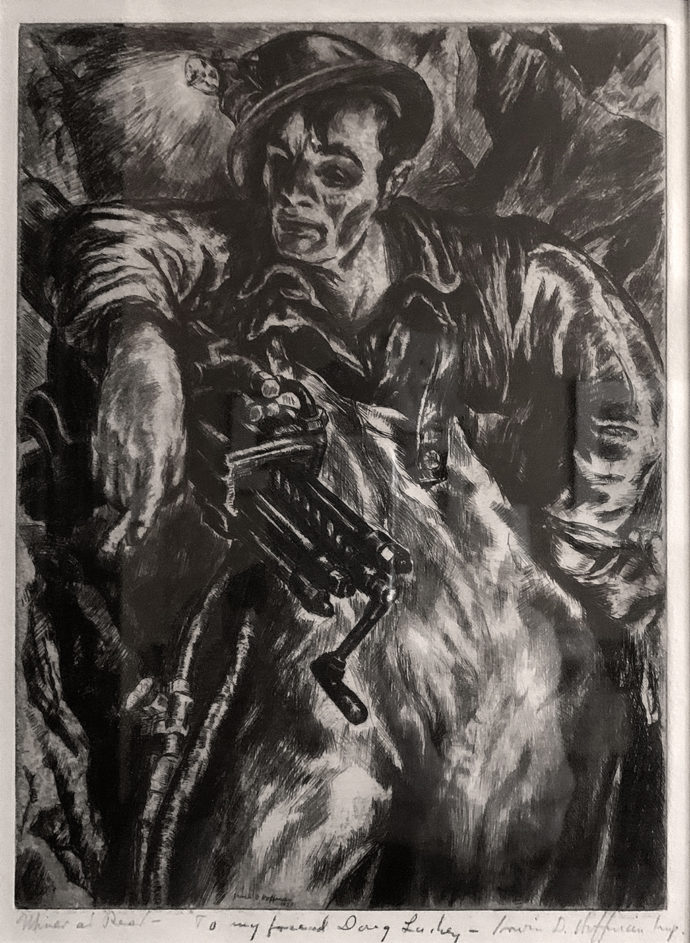

Irwin Hoffman

Irwin Hoffman’s etchings of people seem to fall into two topics: Latin American subjects and laborers in heavy industry. My first two Hoffmans, purchased in the early 1980s from Betty Duffy at her Bethesda Art Gallery, fall into the first category. From the laborers category, this etching–Miner at Rest, 1937, 10 3/4″ x 8″, ed. 100–came from Steven Thomas during a 2012 antiques show in Baltimore. It was published by Associate American Artists, New York. Hoffman (1901-1989) sometimes printed later editions that he would clearly mark as such.

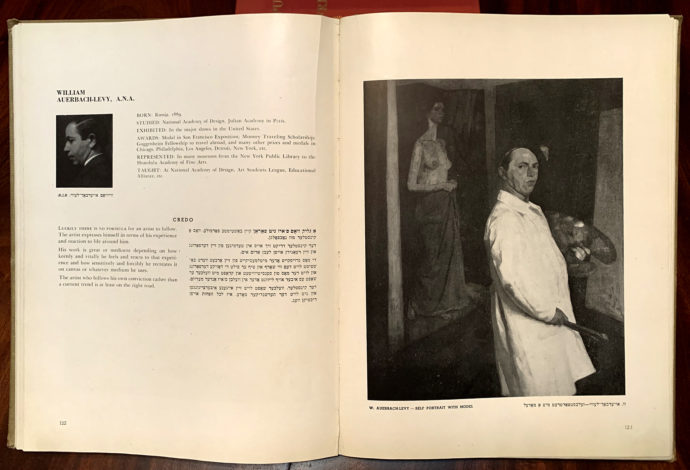

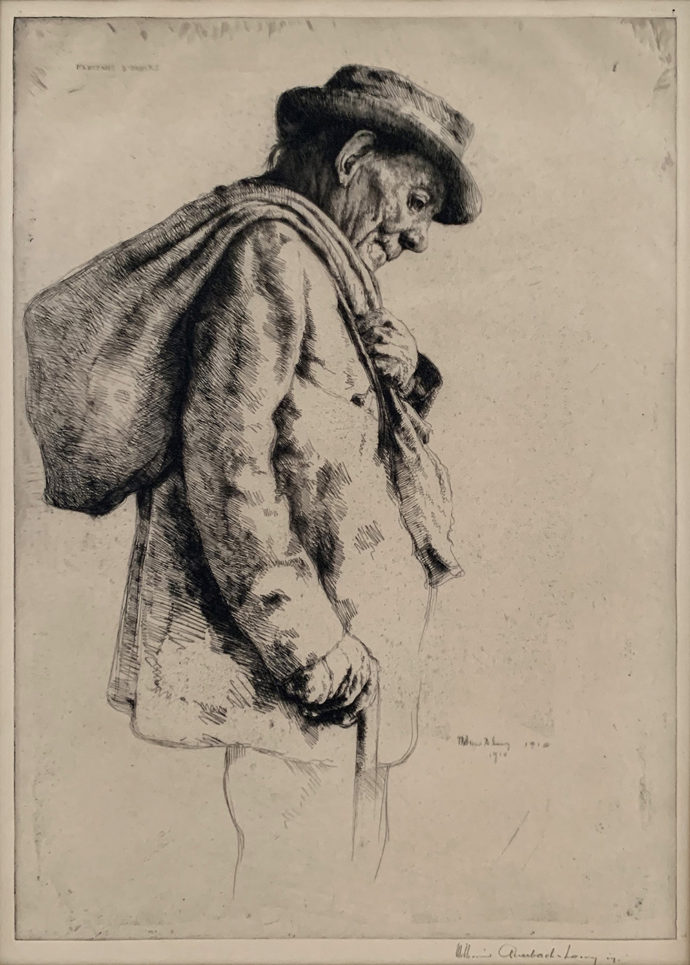

William auerbach-levy

Russian-born William Auerbach-Levy (1889-1979) created his etching Marchand d’Habits (13 3/4″ x 9 3/4″) in 1918. It’s one of several of his prints I bought at auction in the late 1970s at the Harris Auction Gallery in Baltimore for $10 each. This is the only one of the group that I still have. I think I made gifts out of the others. It certainly doesn’t fit in with the more socially conscious images that I soon gravitated toward. Lozowick includes him with other Jewish artists “of an academic bent.”

It was at Harris with its monthly auctions in the 1970s that I tested the waters as a print collector. You can tell I didn’t know what I was doing by the odd array of things that I bought there. One day I should do a blog post on those items I still have. I’ve kept them because they’re instructive in their own way.

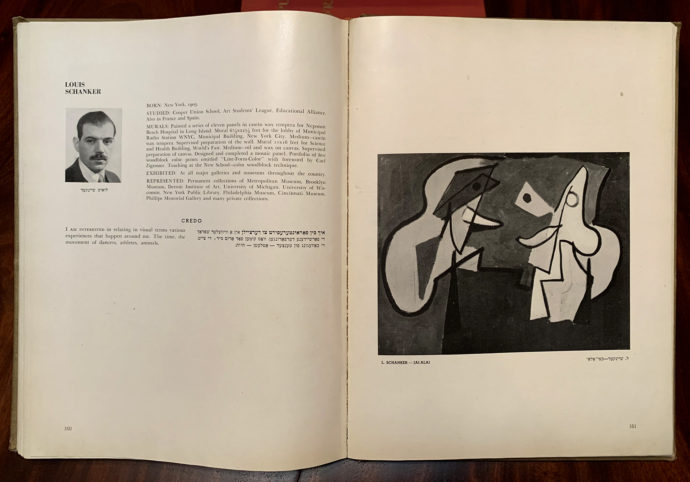

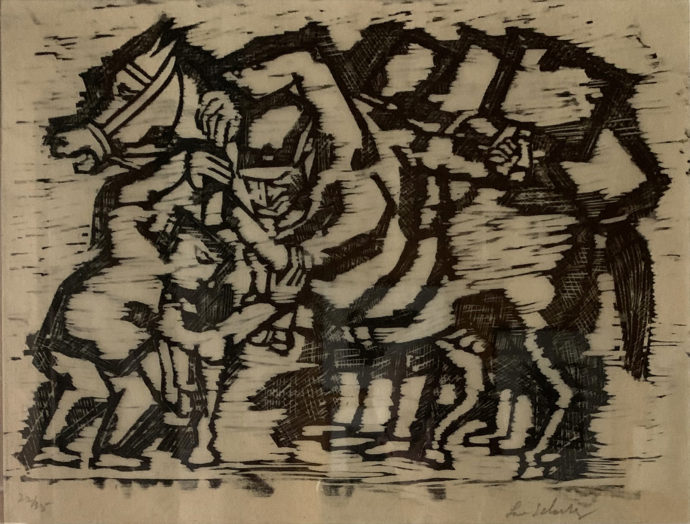

Louis Schanker

Louis Schanker (1903-1981) was a prolific woodcut artist. This print–Cops and Pickets, 1939, 9 1/2″ x 12 1/2″, ed. 35–was likely his most socially expressive image. While he never totally abandoned the human image, his woodcuts, often in color, became very abstract. I was struct how his aggressive digging into the block was a perfect match for the violence depicted.

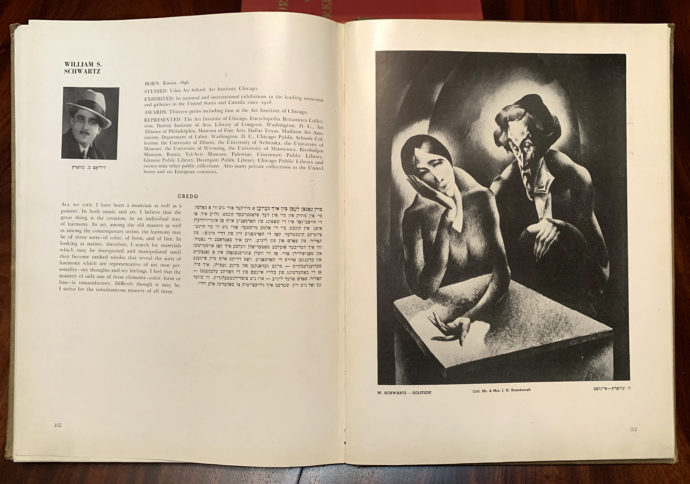

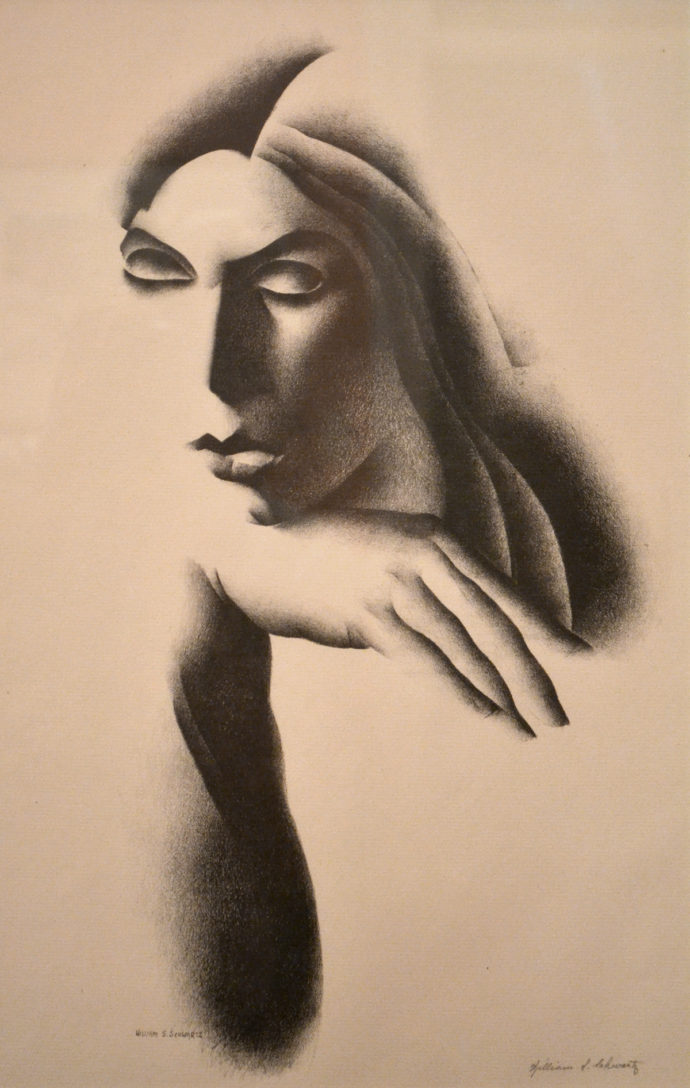

William S. Schwartz

Russian-born William S. Schwartz (18956-1977) created this lithograph–Pensive Woman, 12″ x 9″, ed. 22–in 1930. She was certainly drawn by the same hand that painted the woman in Solitude, the artwork displayed in the Schwartz spread in the Lozowick book.

This was the last print I bought from Betty Duffy. But when I drove to her Bethesda home in 1988 (she had closed her gallery), this wasn’t the print I intended to buy. I wanted the Leon Bibel woodcut Masks and Marchers that was illustrated on her mailed brochure. I asked to see it when I first arrived, but evidently didn’t make a strong enough case that I would buy it. So as I browsed through several other prints, she took a phone call and sold it then and there. I was upset. And the Schwartz was what I left with. A few months later I bought the Bibel (which will appear later in this post) from Ellen Sragow. Considering how rare the Bibel was (edition of 12), I suspect it was Sragow who had bought the Bibel over the phone while I was visiting Duffy.

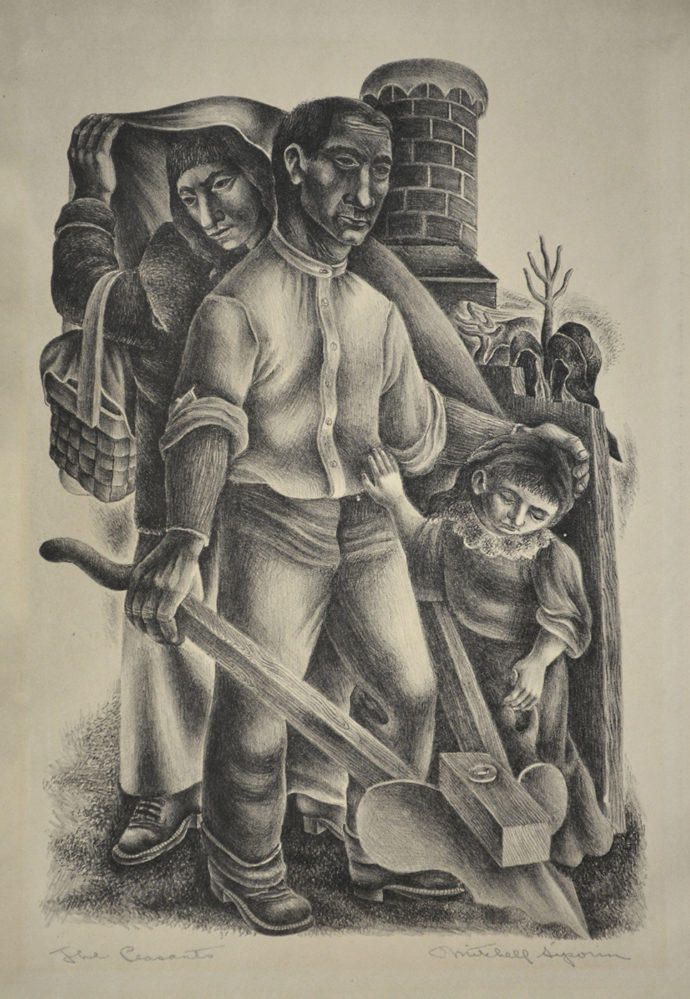

Mitchell Siporin

Born in New York, Mitchell Siporin (1910-1976) grew up in Chicago and studied at the Art Institute of Chicago and with Todros Geller. As the website “Modernism in the New City” (LINK) says of Siporin: “A member of the Artists Union and the Chicago John Reed Club, Siporin was a strong social and political activist. Siporin was appointed to the Illinois Art Project of the WPA in the mid 1930s, and would become one of the most prolific muralists in the Midwest.” He gave this family in his lithograph Peasants (1935, 12″ x 8″, artist proof of second state) great strength and dignity. Siporin founded the Brandeis University art department in 1951.

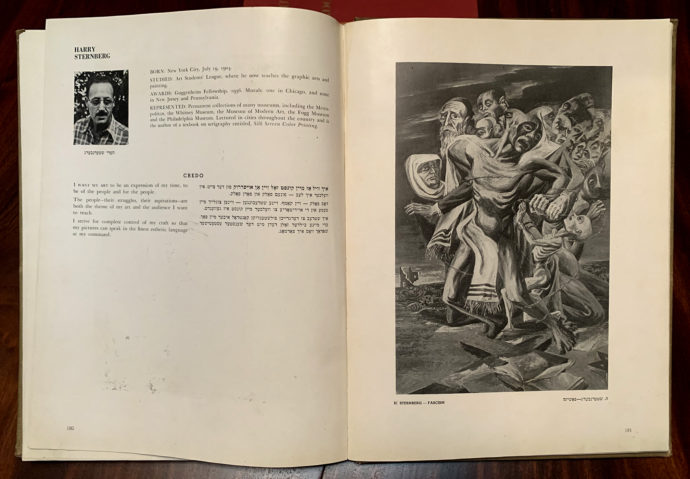

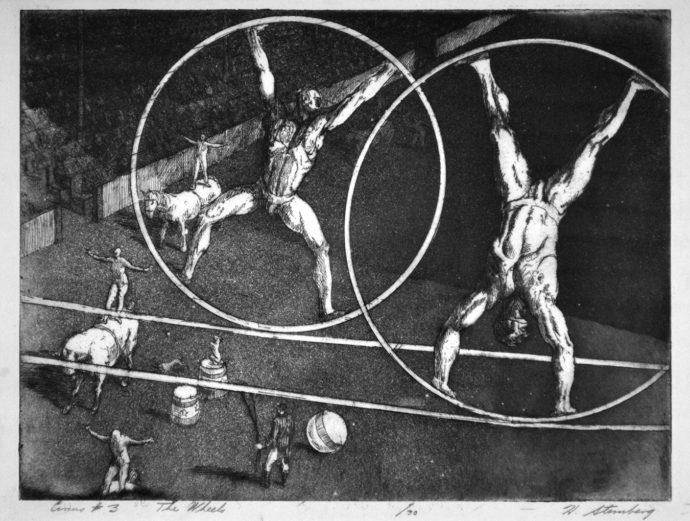

Harry Sternberg

Harry Sternberg (1904-2001) certainly created prints on the social evils of capitalism, as my copy of Bound Man (Enough), a crayon aquatint of 1947, can attest. But I decided to show a print of his more light-hearted side: his delight in the circus. This is The Wheels, an etching/aquatint, 1929, 8 7/8″ x 11 7/8″. In Harry Sternberg: A Catalogue Raisonné of his Graphic Work (James C. Moore, Edwin A. Ulrich Museum of Art, Wichita State University, Wichita, KA, 1975) Sternberg annotated many of the listings. For The Wheels he said: “This high-wire act has never been performed anywhere except in my imagination.” In 1991 Brighton Press, San Diego, published Sternberg: A Life in Woodcuts, for which Sternberg, then in his 80s, created his autobiography in woodcuts. After securing a copy of this book in 2017, I was able to contact Bill Kelly, the founder of the press, and did a blog post. (LINK)

16 other jewish printmakers

I don’t think I ever bought a print because the maker was Jewish. In fact I’ve shied away from buying images of Jewish religious observance. Yet I’ve seemed to have a fair number of prints by Jews who were working in the 20th century, mostly between 1920-1960. It must be something about 1) how they reacted to the world around them and then sought to express what they observed in prints, and 2) what excited my eye when I shopped at print fairs, in dealer’s physical showrooms, at auctions and online.

So after purchasing One Hundred Contemporary American Jewish Artists, I skimmed through my print collection index and made a list of artists (not among the ones listed by Lozowick) that I knew were Jews or I suspected were. Then I went online seeking confirmation. The following are 16 more prints by Jewish artists in my collection.

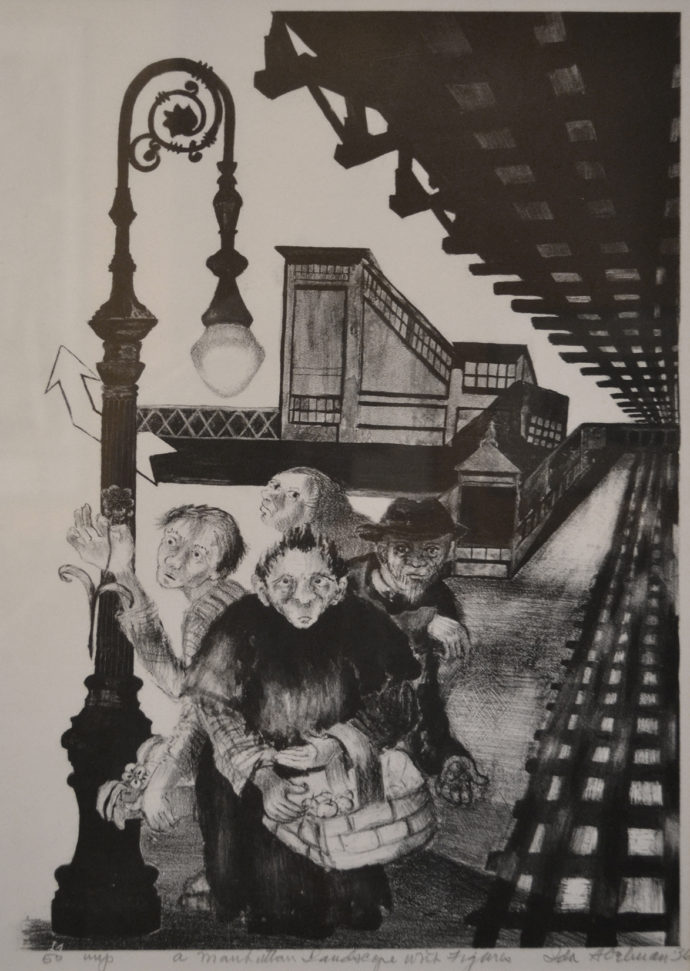

Ida Abelman

This Abelman lithograph–A Manhattan Landscape with Figures, 1936, ed. 50, 13 3/4″x 9 1/2″–was also in the American Artists’ Congress exhibition “American Today.” It’s #99 in the book. Her full name is Ida York Abelman (1910-2002). According to Paths to the Press: Printmaking and American Women Artists, 1910-1960 (Elizabeth Seaton, Marianna Kistler Beach Museum of Art, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KA, 2005), “York” is shortened from her father’s name “Yorkowitz.” He emigrated from Eastern Europe.

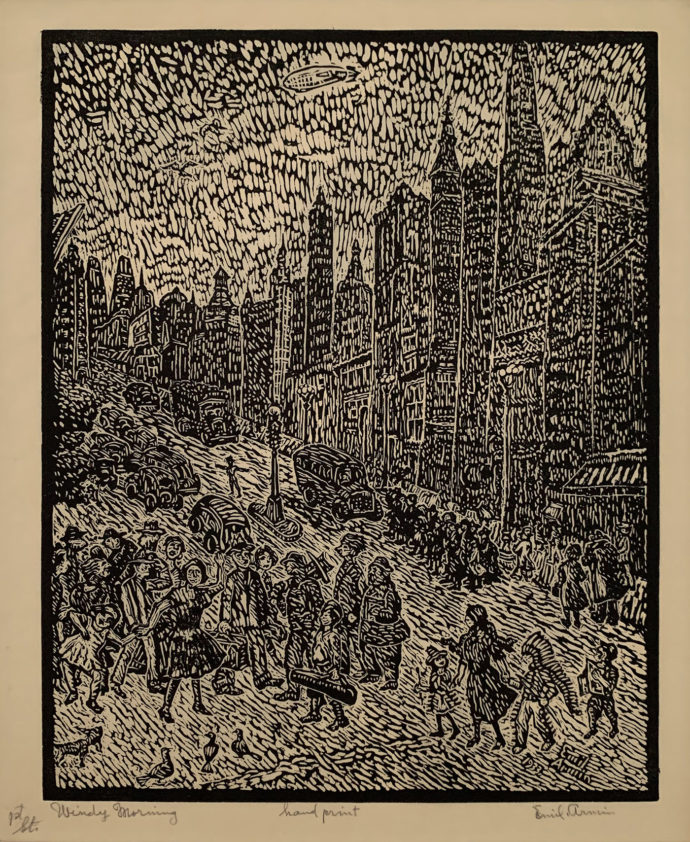

Emil Armin

Emil Armin (1883-1971) was born in what is now Romania. A Wikipedia listing says: “His grandfather was a Jewish scribe, copying sacred scrolls for the local synagogue.” He emigrated to the U.S. in 1905 and joined two siblings who were living in Chicago. Windy Morning–a woodcut, 1933, 9 7/8″ x 7 7/8″, 1st state–seems an apropos title for a Chicago image.

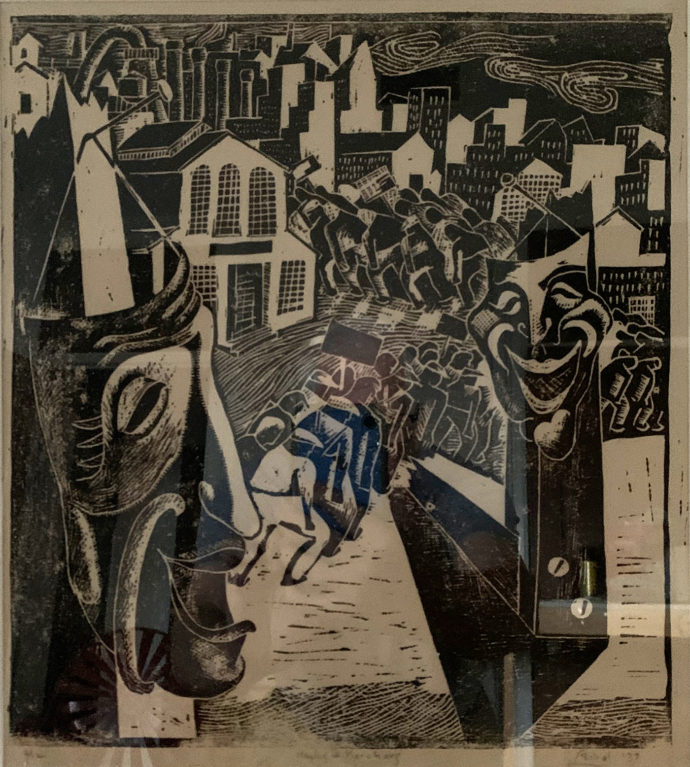

Leon Bibel

Leon Bibel (1913-1995) was born in Poland, growing up in the shtetl of Szczebrzeszyn. His family emigrated to San Francisco when he was a child. In 1936 he moved to join the Federal Art Project at the Harlem Art Center in New York. His Mask and Marchers–linocut, 12″ x 10, ed. 12–was produced a year later. His editions tend to be quite small.

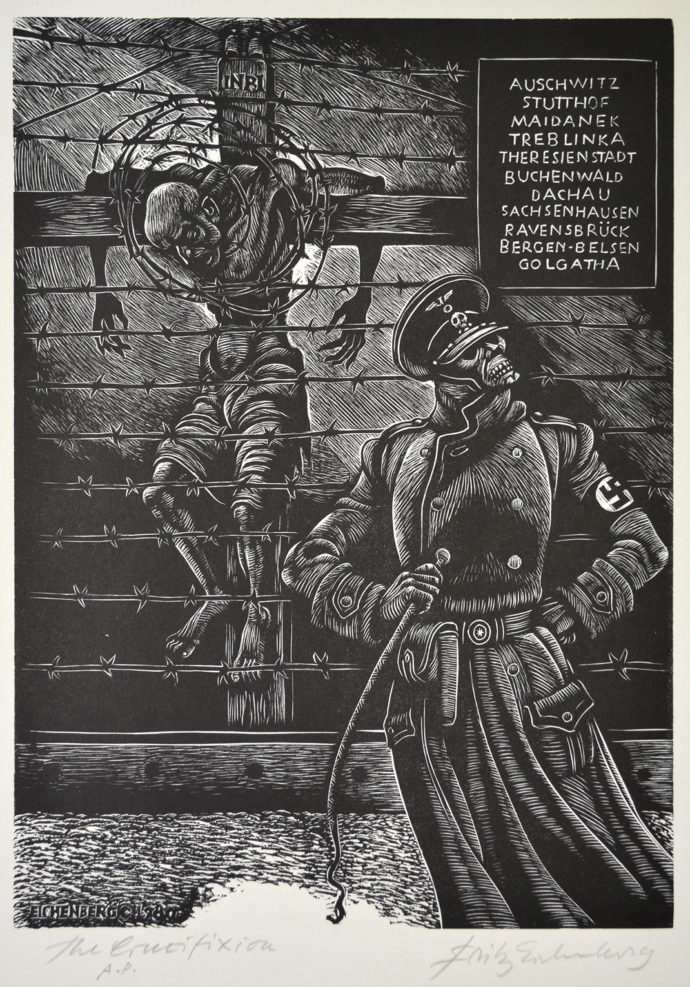

Fritz Eichenberg

Fritz Eichenberg (1901-1990) was born in Germany and moved to New York in 1933 to escape Hitler. While I don’t have any of his small early New York wood engravings, I offer this large one from 1983 since its Jewish theme is terribly evident. The Crucifixion–12″ x 9″–was part of a portfolio of 17 wood engravings he created called “Dance of Death.” I have a complete assembled set purchased from William Greenbaum in 2016.

Isac Friedlander

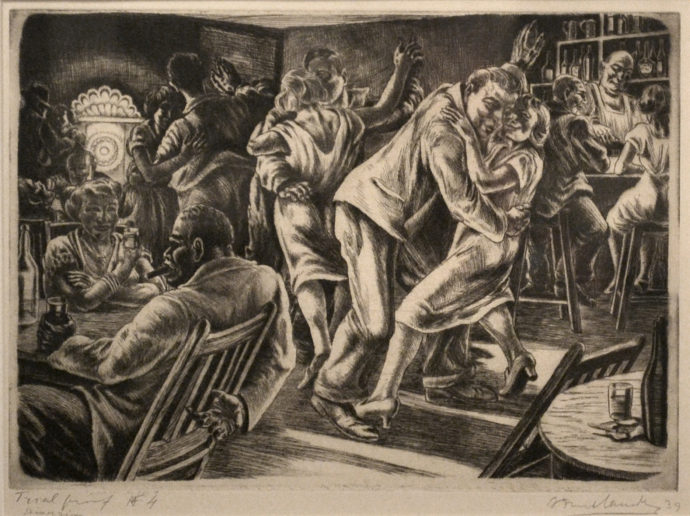

Isac Friedlander (1890-1968) was born in Latvia. On the Georgetown University Library website [LINK] there’s a lengthy bio that includes this episode from his Latvia days: “At sixteen he was arrested and condemned to death, along with several of his classmates, for protesting compulsory uniforms and weekend curfews. His classmates were shot but his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment.” Later with the help of his cousin Joseph Hirshhorn, he emigrated to the U.S. His 1939 etching Diversion–trial proof, 9 7/8″ x 13 7/8″–is fascinating because it depicts an integrated New York tavern scene.

Jacob Glushakow

Jacob Glushakow (1914-2000) was born while his parents–Esther and Abraham–were crossing the Atlantic. They left the Ukraine before the onset of World War I. His Wikipedia listing says he “studied art at the Maryland Institute College of Art, the Jewish Educational Alliance, and at the Art Students League in New York.” For 60 years his artwork reflected his fondness for the street life of Baltimore. Market–lithograph, 11 5/8″ x 9 1/4″–is a good example of his observational skills.

Riva Helfond

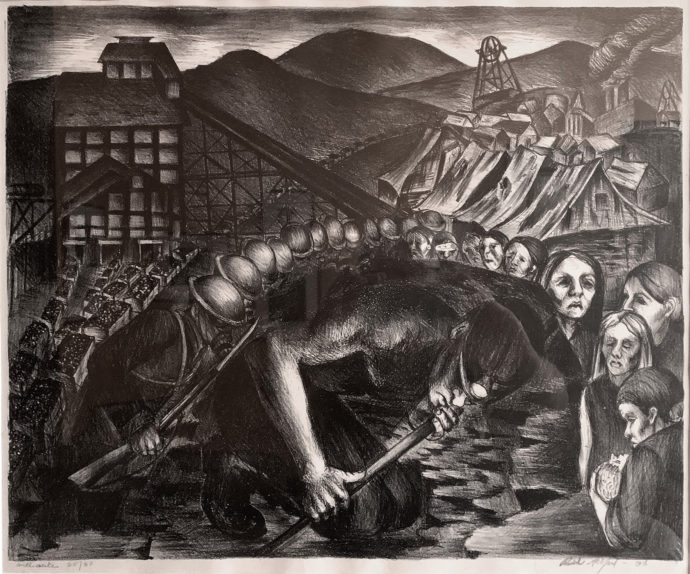

Riva Helfond (1910-2002) was born in Brooklyn to a Jewish family, spent her childhood in Russia, and returned to New York at age 11. The book Paths to the Press has a two-page spread on her, and my blog post on the Gottlieb print The Coal Pickers has a section on the above print. (LINK) Anthracite–a lithograph, 1936, ed. 30, 15″ x 18 3/4″–is perhaps the most harrowing of her coal mining images.

Betty Duffy held a solo exhibition at her Bethesda Art Gallery for Helfond in 1983. When I saw the show, I was quite taken with it but didn’t buy it. A few days later, I called Duffy up to purchase it at $250 (Duffy never gave discounts), but I was told it was sold. She also said the artist was sending up another copy of it but that the price would be $450. Again I passed. BUT soon after Duffy phoned to say that Helfond agreed to sell me this copy for the original $250 price.

Eli Jacobi

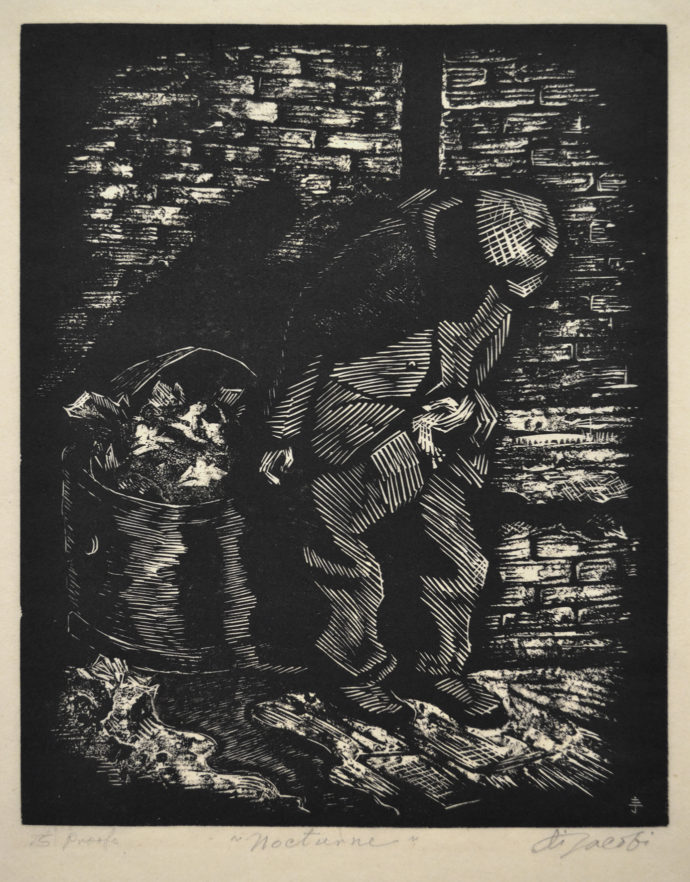

Eli Jacobi (1898-1964) was the subject of an exhibition by the Mary Ryan Gallery in New York in 1986. In the accompanying catalogue, an essay by Elisa M. Rothstein, said that Jacobi was one of 10 children of a poor family in Western Russian. He left his home at age 12 to pursue art training. “The recipient of a scholarship at the Bezal’El Art Institute in Palestine, the young artist studied painting, sculpture, ivory carving, and music for a year before World War I broke out.” He became a portrait painter in Athens. “Upon completing a series of portraits of the Russian Ambassador’s family, Jacobi was offered the choice of enlisting in the Russian Army or being sent to America. He chose the latter, and around 1920 found himself in New York.” The low life of the Bowery became the subject for a number of his linocuts. Nocturne–1936, 9 7/8″ x 8″, ed. 75–was one of them.

Jacob Kainen

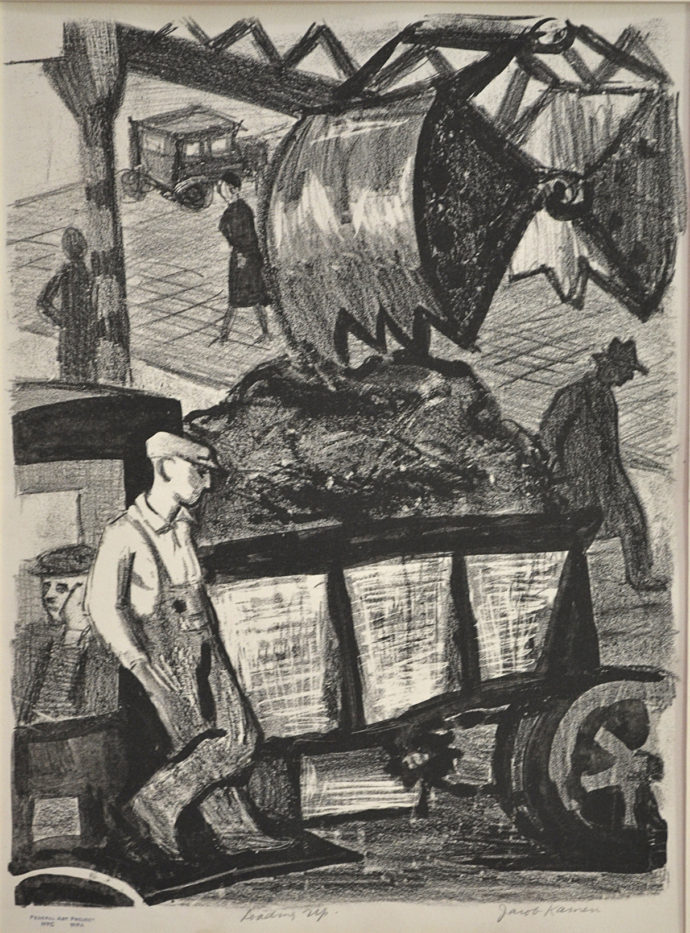

Jacob Kainen (1909-2001) was a printmaker for over 40 years. His style evolved from realistic black-and-white urban scenes, like the print above, to highly abstract color imagery. He was also a brilliant print curator at the Smithsonian Institution. He was born in Waterbury, CT, to Russian immigrants. According to Jacob Kainen: Prints, a Retrospective (Janet A. Flint, The Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, 1980), Stuart Davis encouraged Kainen to join the printmaking program of the New York Graphic Arts Project, which he did in 1935. Loading Up–lithograph, 1939, 14 1/2″ x 11″, ed. about 25–was created during his WPA days.

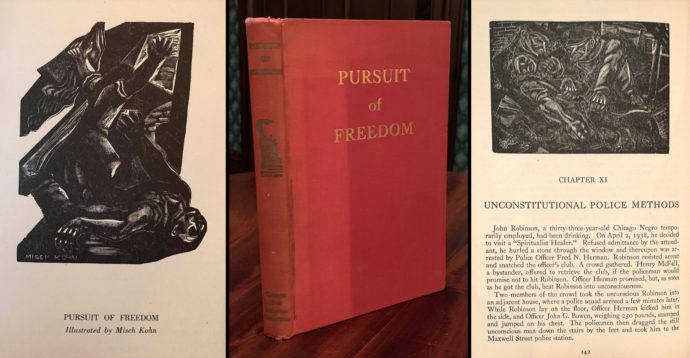

Misch Kohn

This is a very early effort by Misch Kohn (1916-2002), in a style he would soon abandon, but it fits in with this posts parameters, i.e. pre-1947, the date One Hundred American Artists book was published. The full title of this 1942 book is: Pursuit of freedom: A History of Civil Liberty in Illinois 1787-1942 (Chicago Civil Liberties Committee, Illinois Civil Liberties Committee, Chicago). Beside the frontispiece, he made wood engravings for each of the 14 chapters (like the one he did to top Chapter XI, as shown.) From Misch Kohn: Beyond Tradition (Jo Farb Hernandez, Monterey Museum of Art, Monterey CA, 1998): “Harris Kohn was born March 26, 1916, to Russian Jewish immigrants in the small midwestern town of Kokomo, Indiana.” While studying at John Herron Art Institute in Indianapolis in the 1930s, he started to change his name. “He had never liked Harris, but at first he ‘had a hard time finding the right name.’ ” It wasn’t until 1940 that he dropped Harris altogether and called himself Misch Kohn. He became quite an experimental printmaker. I have a very large wood engraving–Warrior Jagatar–from his middle period, but I’ll save that for a future blog.

Ruth Leaf

Ruth Leaf (1923-2015) was born to Russian immigrants in Brighton Beach, New York. At 19 she enrolled at the Art Students League and took printmaking lessons from Harry Sternberg. This woodcut–Orchard Street, 8 3/4″ x 18 1/4″, ed. 35–probably dates from the early to mid 1940s. By 1946 or 1947, she became a member of Atelier 17, Stanley William Hayter’s studio in New York. Under Hayter’s influence, she started experimenting with color printing. Before she died, there was a website devoted to her work. I asked about Orchard Street but never got a reply.

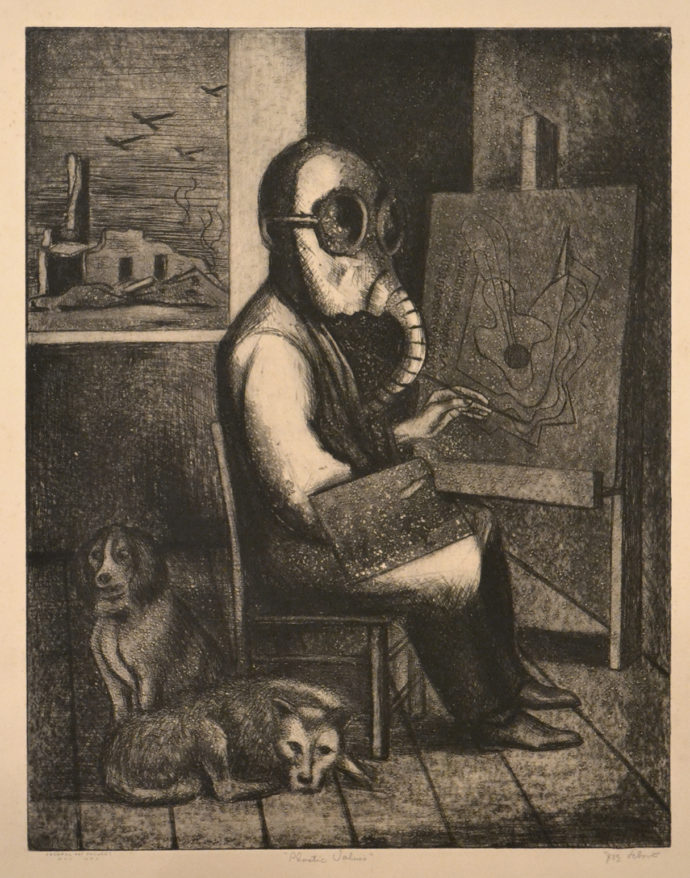

Joseph Leboit

This Joseph Leboit (1907-2002) etching and aquatint–1936, 14″ x 10 7/8″–was the subject of the ART I SEE blog in January 2016. (LINK) That post investigated why my copy is titled Plastic Values while the print is better known as Tranquility. Leboit was born in New York as Joseph Leibowitz. According to his bio on the Annex Galleries website: “In the mid 1930s Leibowitz changed his name to Leboit, though whether it was due to mounting anti-Semitism or the art world’s growing affinity for French artists is unknown.” After the war he trained as a psychologist and as “a certified psychologist and for twenty-five years served as director of the Advanced Center for Psychotherapy, a non-profit mental health clinic, which he co-founded.”

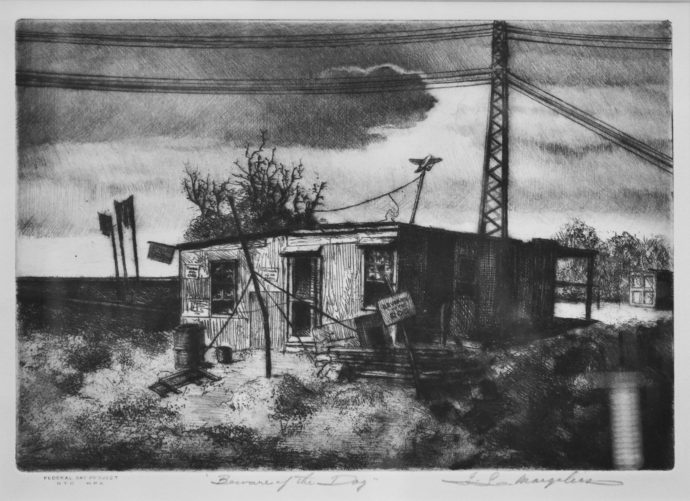

Samuel L. Margolies

Jane Margolies wrote an article in The New York Times entitled “My Grandfather was a Famous Artist; He Also Made Greetings Cards.” [LINK] She said: “Born in 1897 on the Lower East Side to Jewish immigrants who had fled czarist Russia, Samuel Margolies [died 1974] studied at Cooper Union, the Art Students League and the National Academy, first painting and doing bronze sculptures before discovering etching.” He is best known for etchings of skyscraper construction in Manhattan. My print–Beware of the Dog, etching, 1936, edition probably 25, 6 7/8″ x 9 7/8″–is of a much more humble structure.

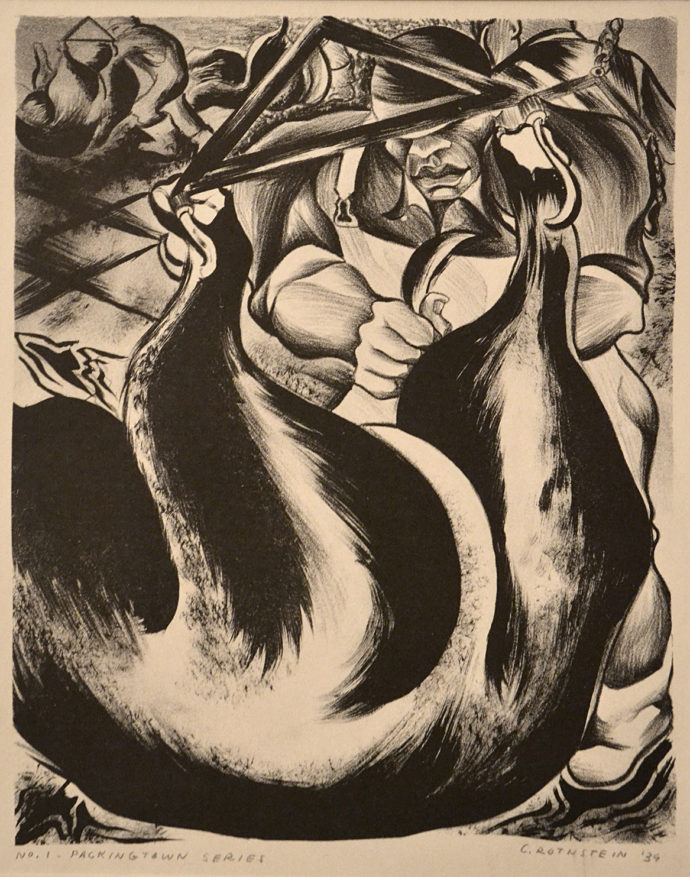

Charlotte Rothstein

Charlotte Rothstein (1912- ) studied at the Art Institute of Chicago, under Todros Geller and Rudolph Weisenborn. The Art of the Print website has a short bio (LINK) in which it says: “Rothstein’s art gained a national reputation in 1939 when several of her paintings were exhibited at the World’s Fair in New York. She later participated in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Exposition and was a frequent contributor to the annual exhibitions at the Chicago Institute of Art. Charlotte Rothstein was a full member of the Chicago Society of Artists, the United American Artists and the American Art Congress. Not the least of her accomplishments was her involvement in the early beginnings of silk-screen prints.” While not a kosher subject, her No. 1 Packingtown Series–lithograph, 1939, 9 5/8″ x 7 5/8″–shows a beautiful handling of both liquid and crayon-form tusche.

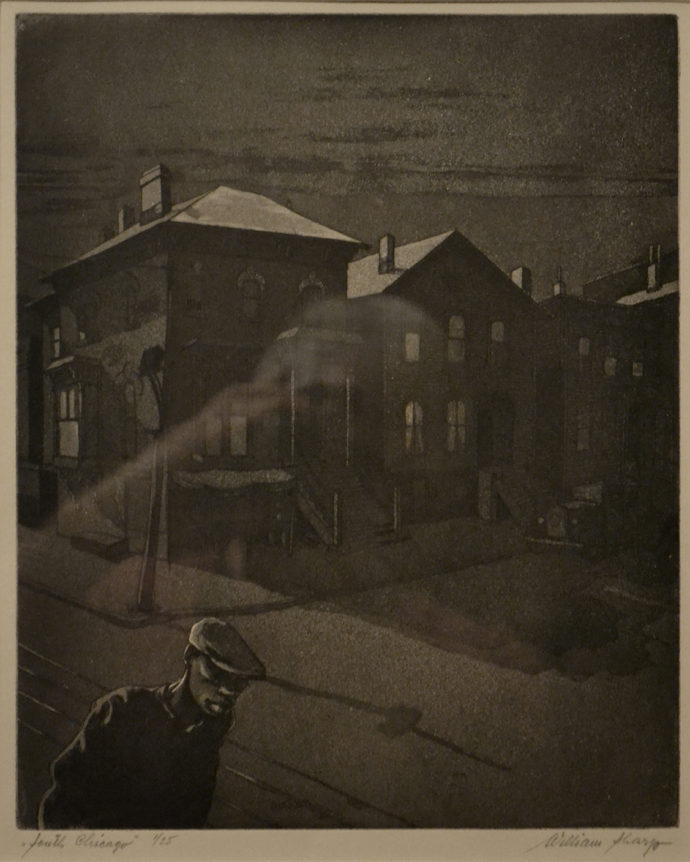

William Sharp

From a bio on the Kiechel Fine Art website (LINK) William Sharp (1900-1961) was born in Austria and served in the German army in World War I, after which he became a newspaper artist. “Sharp drew political cartoons that were bitterly critical of the growing Nazi movement. As the influence of National Socialism intensified, he began to contribute drawings, under a pseudonym, to publications that were hostile to Hitler. After Hitler assumed power, Sharp was confronted with these drawings and told that he would be sent to a concentration camp. However, in 1934, he escaped to the United States.” The Brier Hill Gallery website ( LINK), meanwhile, said Sharp was born Leon Schleifer and that he changed his name to William Sharp once he arrived in the U.S. His 1938 print South Chicago is an etching/aquatint, ed. 25, 10 7/8″ x 8 3/4″.

From a bio on the Kiechel Fine Art website (LINK) William Sharp (1900-1961) was born in Austria and served in the German army in World War I, after which he became a newspaper artist. “Sharp drew political cartoons that were bitterly critical of the growing Nazi movement. As the influence of National Socialism intensified, he began to contribute drawings, under a pseudonym, to publications that were hostile to Hitler. After Hitler assumed power, Sharp was confronted with these drawings and told that he would be sent to a concentration camp. However, in 1934, he escaped to the United States.” The Brier Hill Gallery website ( LINK), meanwhile, said Sharp was born Leon Schleifer and that he changed his name to William Sharp once he arrived in the U.S. His 1938 print South Chicago is an etching/aquatint, ed. 25, 10 7/8″ x 8 3/4″.

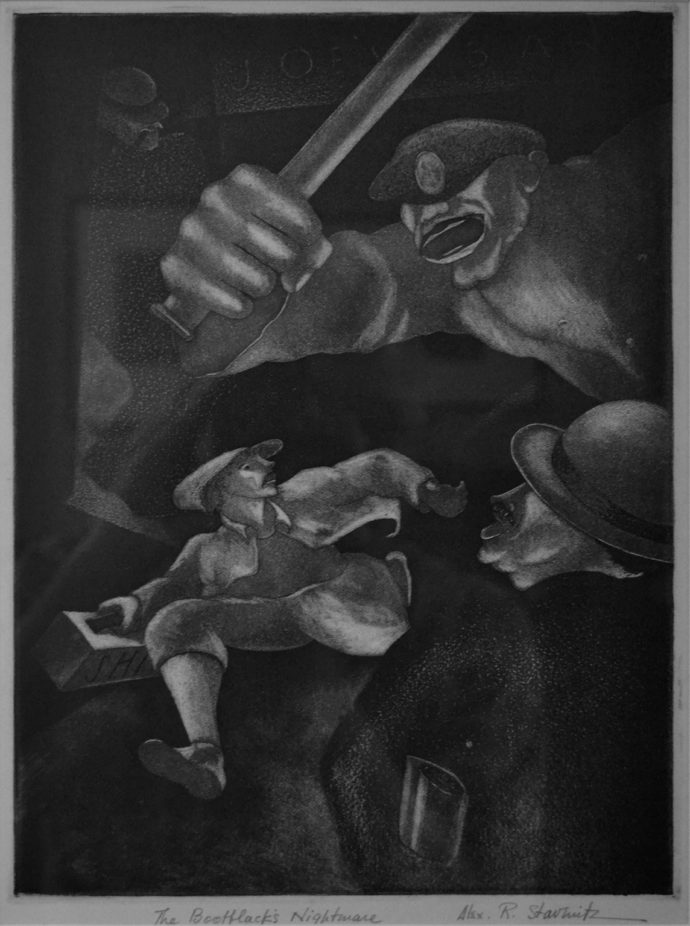

Alex R. Stavenitz

Alex Raoul Staventiz (1901-1960) was born in Kiev, Russia, but lived and worked most of his life in the U.S. He was a member of the American Artists’ Congress and wrote the initial part of the introduction to the book American Today. While Louis Lozowick fails to name the selection panel for YKUF’s book One Hundred American Jewish Artists, Stavenitz names the 13 artists on the America Today selection committee. (Louis Lozowick, who wrote the essay in the YKUF book, was on the American Artists’ Congress committee.) Stavenitz wrote: “The exhibition, as a whole, may be characterized was ‘socially-conscious.’ It reflects a deep-going change that has taken place among artists for the last few years–a change that has taken many of them not only to their studio window to look outside, but right through the door and into the street, into the mills, farms, mines and factories.” The Bootblack’s Nightmare–etching/aquatint, 1936, 11 3/4″ x 8 5/8″–was print #76 in American Today.

I think Staventiz’s summary of the contents of the exhibition well reflects what I look for in selecting a print: imagery that proves the artist left the studio and went “right through the door.” The 29 Jewish artists presented in this ART I SEE post certainly did that.

endnote

If you wish to add a comment to this blog post, please write to me at: p1m1@comcast.net

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/american-jewish-artists-pre-1947/trackback/