Remedy for Rethel: Conserving 1840s broadsheet

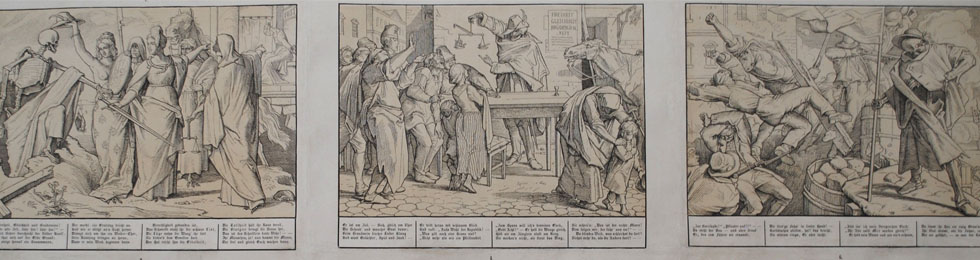

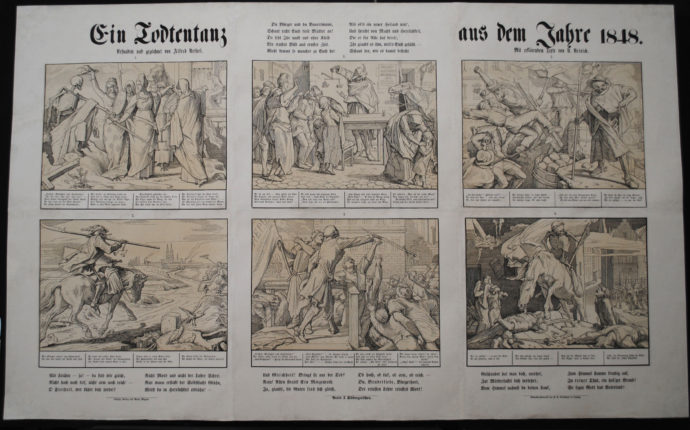

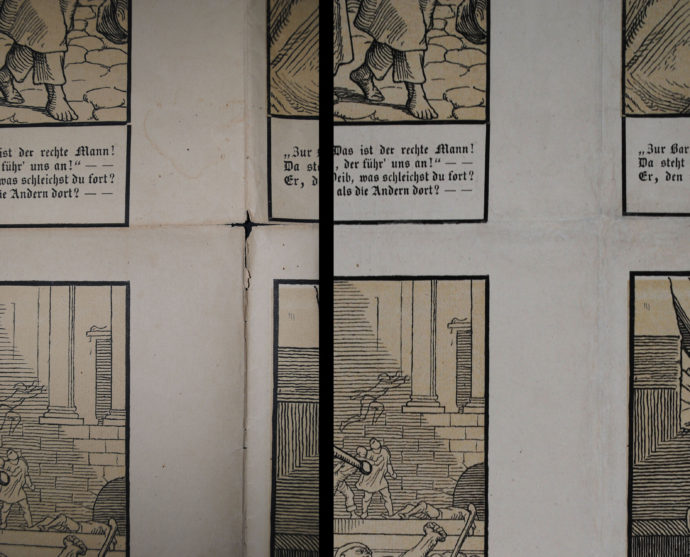

Antiquariat V.A. Heck sent me these images of the Rethel broadsheet in July 2017. The broadsheet was first published in 1849 by Georg Wigand (German, 1818-1858) and printed by F. A. Brockhaus, Leipzig. It measures 28 1/8″ × 45 7/8″.

Introduction

I hadn’t realized that it took me over two years to decide to purchase German artist Alfred Rethel’s 1849 broadsheet Ein Todtentanz aus dem Jahre 1848 until I completed my first blog post on its historical significance on 30 July this year. (See http://www.scottponemone.com/rethels-death-as-counterrevolutionary-meme/) Above are images the Austrian antiquarian book dealer V.A. Heck sent me in February 2017. With splits to the paper along the folds, earlier repairs and darkening of the paper, the need for conservation was obvious. So I forwarded these photos to Thomas Primeau, former chief conservator at the Baltimore Museum of Art. In response, Primeau–then at the National Archives–said:

“I have always thought that these were interesting prints,. I didn’t know that the series was also printed on a single sheet. The condition appears to be stable, but somewhat deteriorated with noticeable darkening on the reverse and tears. At the minimum, I would recommend repairing the tears, but, if the paper is very brittle, then you might consider a washing/de-acidification treatment. Without seeing the work in person, I would say the range for conserving the print would be $250-$500. It is probably safer to store the work open as repeated folding could cause more tearing.”

That put the purchase on hold until May of this year. As reported in the previous post, it wasn’t until a second copy became available that I finally made my purchase. The second copy at first appeared in much better shape, but it turned out that all of the elements on this copy had been assembled (collaged) onto a new piece of paper. So restoring an intact, but deteriorated broadsheet seemed to be the proper way to go.

This post then recounts the conservation of the Rethel broadsheet.

The Project

Soon after the Rethel arrived from Vienna in late May 2019, I again emailed Primeau to see if he would be interested in taking on its needed conservation. But on 11 June he wrote: “Thank you for thinking of me for this interesting project. I am now living in Philadelphia and currently am not set up to take on any projects. You could reach out to Linda Owen, who is now at the BMA to see if she is taking on outside work or can recommend someone in the area.”

So I turned to Owen, but on 24 June she responded: “Thanks for your email and sorry for the delayed response. I’ve been wading through my inbox and catching up on things today. I don’t usually do private work myself, but I am happy to recommend some conservators in the DC or Philadelphia area. Unfortunately, there aren’t any paper conservators in private practice in Baltimore right now. In Philly, I would suggest CCAHA, a regional paper conservation lab. In DC there’s Im Chan and Amy Hughes, a fellow at the National Gallery of Art. I am not sure what email Amy is using for private work; I will forward it on to you when I hear back from her.”

Since I don’t seem to have a record of further correspondence from Owen, I assume I never got an email address for Amy.

Website masthead for Cleveland Conservation of Art on Paper, Inc. http://conservationofpaper.com/welcome.html

Maybe I didn’t even wait. I seemed to have immediately done my own web search and found Cleveland Conservation, operated by Rachel-Ray Cleveland and located near Laurel, MD (about 25 miles south of Baltimore). In her first email correspondence (26 June), Cleveland said, “That sounds like an interesting poster…. What you describe–folds with small areas of paper missing at the intersection of folds–is a common type of repair we routinely carry out here at Cleveland Conservation with very good results.”

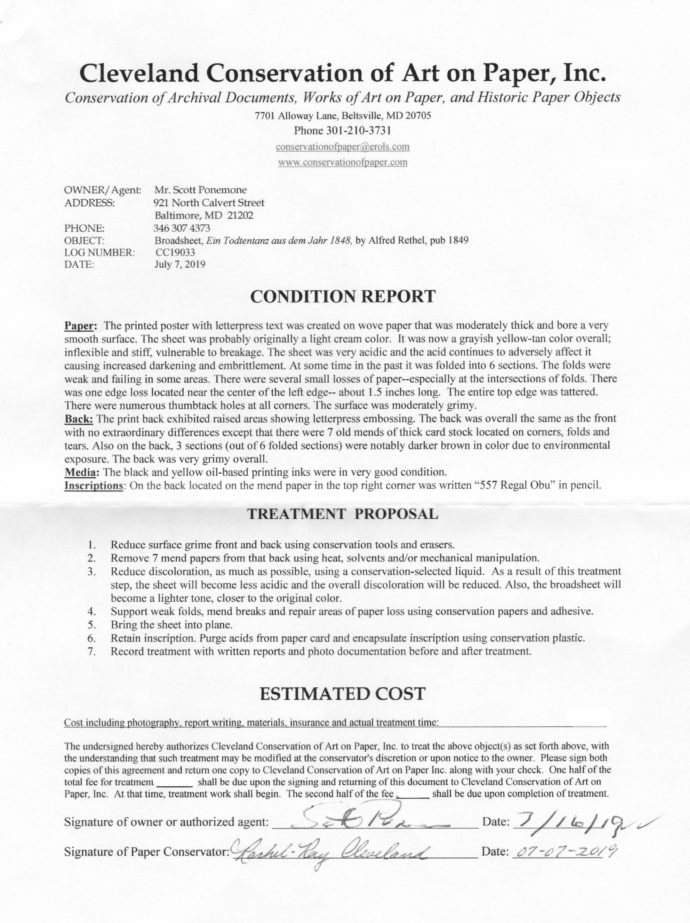

We then talked on the phone and set up a $50 consultation at her office on 5 July. Her workspace turned out to be in a converted two-car garage attached to her suburban colonial. Upon arrival, I unfolded the Rethel and she made a quick assessment. In short she said she will need to test the inks to see if they can be treated without adverse effects; otherwise she said she shouldn’t have any trouble mending the tears to the paper. She promised a condition report along with a treatment proposal and cost estimate in a few days. She also showed me her lab and ongoing projects. Her results were impressive.

The following week her report arrived. The estimate, which I’ve erased on this jpg, was noticeably higher than Primeau’s $250-500 range and about a third more than the price for the Rethel from Heck in Austria. But I was committed to its conservation, and, as you can see to the right, I signed the proposal on 16 July and sent a check for half of the estimate. The contract gave her a generous completion date of 30 Jan. 2020.

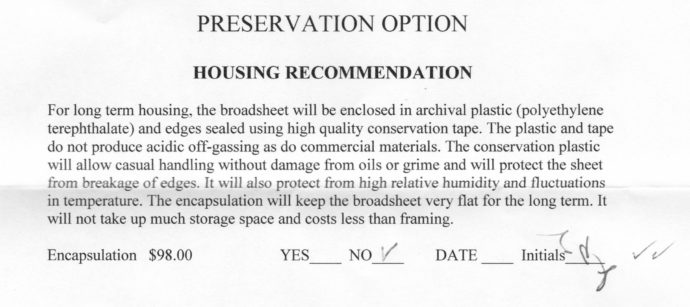

But before I signed the contract, we had a vigorous exchange of emails regarding the second page of her proposal with its “Preservation Option.” In short she recommended sealing the Rethel in a plastic enclosure, which she called encapsulation.

I admit I find the whole idea of encapsulation quite odd and quite opposite of how museum’s preserve their works on paper. For over 40 years I’ve been a guest at times at the study room for the Department of Prints, Drawings & Photographs at the Baltimore Museum of Art. Never have I’ve seen encapsulation of an artwork on paper. Most works were kept in folders composed of all-cotton acid-free boards. Any tissue paper or adhesives that were used were also archival. And when curators brought a requested artwork into the study room, they would remove any tissue or covering so the viewer could study the piece face-to-face, so to speak. No plastic covering stood between viewer and artwork.

Maybe encapsulation would be appropriate where the owner was not aware of archival materials and had no print cabinets for storage. But as a print collector with over 40 years experience, I felt encapsulation was not for me. Emotionally, I equated encapsulation with mummification, that my Rethel, if encapsulated, would no longer be a living document, that I would no longer be able to view it face to face.

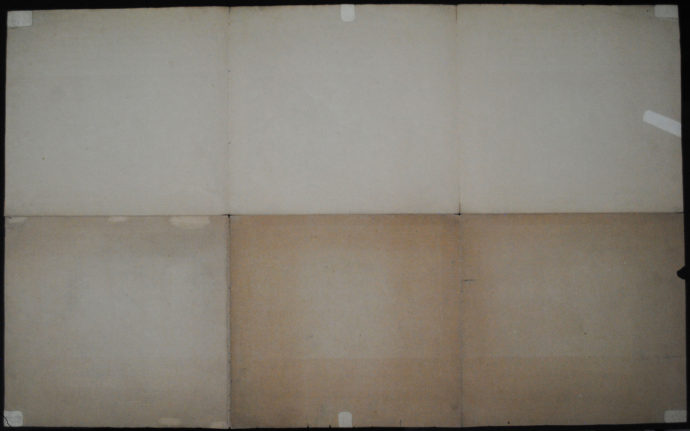

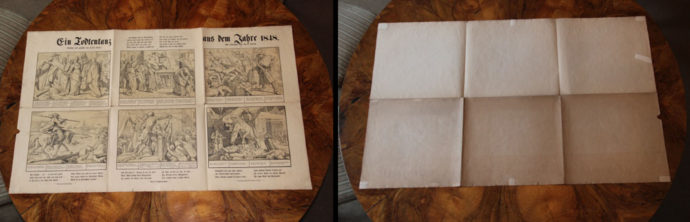

Rachel-Ray photographed my Rethel broadsheet front and back in order to document its condition before she began her treatment regimen.

Thus I began an email exchange with Cleveland about her “housing recommendation.” I wrote on 11 July: “My only issue deals with encapsulation. While I like the idea of an archival plastic sleeve, I don’t want it sealed. I prefer some type of enclosure (Velcro or Ziplock) that would allow me to slip it out for talks. It would also need a support piece of stiff, light-weight acid-free paper underneath that the Rethel could rest on and sit on when it is slid out of and returned to the sleeve.”

Her response was immediate:

“It is your object as the owner so the decision on how to house it is entirely yours. I am simply advising you and I am letting you know that sliding a large paper object in and out of a plastic “L” sleeve (closed on two sides) can be an invitation to damage. This object is large, floppy and bears fragile edges. In addition, sliding in and out of a plastic sleeve–even with a sheet of support paper behind it–is awkward. This is because it is a very large sheet that is unattached to the support sheet underneath it and because the plastic itself has magnetic character, tending to cling to the poster and to the support paper behind it. For these reasons, I do not recommend an “L” sleeve for housing–especially if you intend to remove it from the sleeve and then place it back in the sleeve. Damage can be incurred easily.

“Likewise, I am unaware of any manufactured Ziploc bag that would be of the large size dimensions of the poster. In any case, even if there were such a thing, it would likely be made of recycled polyethylene and/or polyester and it would likely off-gas deleterious by-products over time that would be trapped inside the enclosure. Commercial products like Ziploc bags are not manufactured with conservation applications in mind. I would not recommend using them. In conservation housing, we use only virgin materials that have not been recycled.

“The other option is to house it in a four-flap archival portfolio which would be safe and easy to open and close for viewing purposes. It would be made of 100% cotton and would be adjusted to pH 8.5. I believe we discussed this option at our meeting and you felt it was too bulky. It is also more expensive than encapsulation. In any case, you are welcome to house your object in any way you would like. The encapsulation housing sounded like what you were seeking–a convenient and accessible housing that is easily transported and stored. You might be interested to know that the encapsulation option (four sealed edges) is always backed with a high quality sheet of archival paper directly behind the object as a standard procedure.

“Please let me know what you prefer to do regarding housing. As mentioned above, this decision is entirely up to you. Presently I believe you have a quote for encapsulation. If I can provide any addition information, let me know.”

Well, I asked her to price a portfolio even though I still felt it would be too bulky. She wrote back on 13 July:

“Scott, as requested, I have researched the materials needed for your four-flap archival portfolio. Unfortunately, the poster itself is larger than the typical 32 “ x 40” paperboard. The object itself is about 29 “ x 46”. Purchase of a larger paperboard 40 x 60 is uncommon to find and is more expensive to ship. So the price for an oversized portfolio is not inexpensive. It is, however, superior to the type of protection one may get with framing because the archival portfolio effectively seals out air pollution and light damage. It also costs less than framing.

“The archival four-flap portfolio I am proposing will be gray on the outside and white on the inside. The paperboard will be condition to pH 8.5 using calcium carbonate. The inside will be a clean, ideal environment for preservation of paper. In addition, the gray outside will bear a thin acrylic coating that repels water (should it ever be in way of a fire sprinkler) and also resists dirt and dust. There will be a formal presentation label on the outside and it will say whatever you decide to put on it. The price for the portfolio is $290. If you would like to proceed with this, then please let me know.”

Maybe it was just the added cost (I was quite sensitive to how much her treatment regimen was going to cost) or maybe it was the prospect of a bulky portfolio taking up room in a print cabinet drawer, but I rejected a portfolio as well. I wrote back: “I’m going to get two sheets of 40×60 100% cotton museum board and cut them down to 50×35 and hinge them with linen tape. And if you could provide two sheets of archival paper you would use for encapsulation, I think that would be sufficient protection when stored in my oversized flat files. I’ll mail you the contract with a check for half the estimated cost.”

Yet, she gave it one more try:

“Of course, as previously stated, the choice about housing is up to you. To be clear, the original proposition of encapsulation using archival plastic will preserve present flatness (after treatment) and will serve as a barrier to the damaging influences of various environmental factors–especially fluctuations in relative humidity and temperature.

“By contrast, a simple folder, as you describe it, will not serve this type of protection and will likely result in eventual planar distortion such as waviness and cockling. I am writing this in order to have a clear understanding with you–so that when these problems of planar distortion (waviness, lumps, cockling) do arise, you understand that I did not recommend the simple folder type of housing and I am not responsible for the planar distortion you will be likely to incur as a result of that type housing.”

With that, I signed the contract, wrote a check for half of the estimate and mailed them back to her.

Restoration

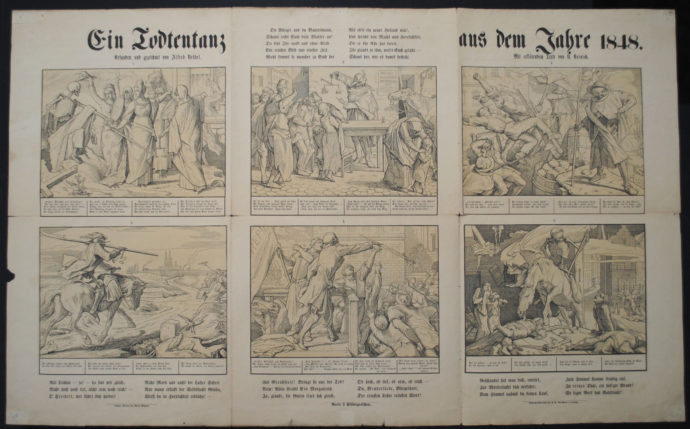

On 11 October Cleveland notified me: “The poster is nearing completion and I am happy to say that the treatment has produced very nice results. It now looks so much better and, most importantly, it is now chemically stabilized. The acidic content has been reduced, the weak folds have been supported, small areas of missing paper have been inserted in areas of loss along edges, and the coloration of the sheet is now overall more nearly what the artist intended it to be.”

And she gave encapsulation one more try:

“According to my records, you declined my recommendation for encapsulation. As I have explained, items of this type are sometimes lined with a new sheet of Japanese paper on the back side in order to increase support for fragile paper and insure flatness of an oversized sheet. Because you have requested that there be no lining, and because of the nature of the paper and repairs, this sheet may not retain complete flatness over time. Also, as I have mentioned before, fragility of the edges may result in damage if handled repeatedly without the protection of encapsulation. You and I have already discussed these things in previous e-mails; however, I am mentioning them again to insure we have clear communication. If this historic object were mine, and I intended to transport it to various venues for display, I would encapsulate it in archival plastic with 4 sealed edges. I would also consider enclosing it in an outer folder or portfolio of some kind. Please also be aware, since you have not contracted for an enclosure of any kind, the poster will be wrapped in buffered tissue paper and supported between nonarchival sheets that are temporary for transport purposes only.”

At the same time she requested $33.68 above the estimate to cover 6 percent MD sales tax for materials. While she could raise the final cost above the contracted estimate, I found this amount curious. If $33.68 represented 6 percent of her materials expenditures for materials, then her materials’ cost would be significantly higher than her labor. So I asked her: “Can you provide an invoice that breaks down materials and labor?” (Just like an auto mechanic would.) At that point she simply said: “You are welcome to simply remove the tax from your bill as will I.”

Rachel-Ray Cleveland lifts the tissue off from the Rethel broadsheet for my inspection. (Photo by Scott Ponemone)

On 24 October I arrive at Cleveland’s house with an acid-free 4-ply matboard folder in hand. It measured 47″ x 32″, just barely fitting my largest print cabinet. Her work, I must say, was quite immaculate. She managed to lighten the whole sheet, which allowed the pale buff tones that lay beneath the six wood engravings of Rethel’s picture cycle to be more distinct. Her mends and patches beautifully matched the broadsheet paper.

She also provide before (left) and after treatment photos of where folds had crossed and a hole had opened up. Even the faint water stain above the horizontal fold had all but disappeared.

Hoping to have Cleveland share her thought processes and logistics of her conservation efforts, I asked her “what steps you took to mend the hole where the folds cross.” But in providing a digital copy of her treatment report, she stated: “That is all the information I have to share.”

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/remedy-for-rethel-conserving-1840s-broadsheet/trackback/