Eric Avery: Doctor of Printmaking

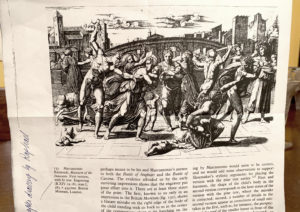

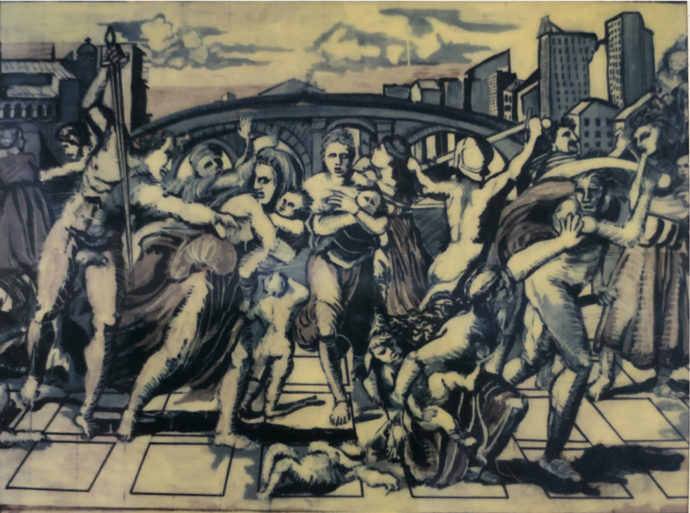

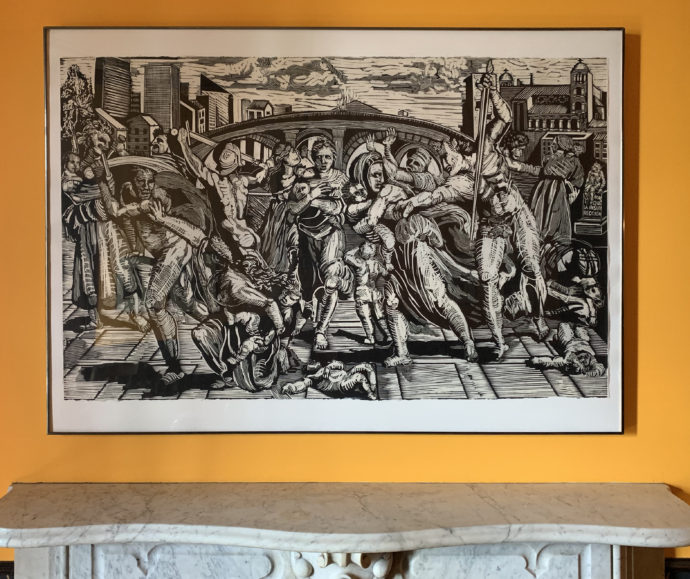

Eric Avery (American, born 1948), “Massacre of the Innocents,” linoleum block print on handmade Okawara paper, 37″ x 50″, 20/25, 1984. Printer: Tony Lujano, San Ygnario, Texas, 1986. (Photo by Scott Ponemone)

Introduction

Ever since I purchased Dr. Eric Avery’s huge linocut Massacre of the Innocents in 1994 from Judith Brody, who ran a gallery just north of the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC, it hung in my dining room just above the mantelpiece, where no doubt an immense gilt mirror was originally.

As you can imagine, Massacre has been quite a conversation piece when guests come to diner. Fortunately, Brody had given me a photocopy of the Italian Renaissance engraving that Avery based his print on, i.e. Marcantonio Raimondi’s Massacre of the Innocents. So whenever Massacre arose as a dinner topic, I would dutifully pull out the photocopy, which was handily stored in a sideboard drawer. Notice, I would say, that Avery’s version is reversed left-and-right from Raimondi’s. I would also point out that Avery made the buildings in the upper left to appear like modern skyscrapers. And that’s how far the conversation would go.

Then last winter I viewed the exhibition The Chiaroscuro Woodcut in Renaissance Italy at the National Gallery of Art. The word chiaroscuro literally translates in Italian as “light-dark.” A chiaroscuro woodcut is created with at least two blocks; one (key) block to carry the dark lines of the image and one block to present a middle tone. Additional tone blocks could add shading to the image. The German Hans Burgkmair (1473–1531) is credited with its invention; while the Italian Ugo da Carpi (c. 1480–c. 1532), who also claimed its invention, perfected the technique in Italy.

With one major exception all of the prints in the exhibition, if my recollection is correct, were woodcuts. That exception, in the show’s last room, was Raimondi’s Massacre of the Innocents. And beside it was Ugo’s Massacre of the Innocents, his chiaroscuro woodcut take on the Raimondi.

Marcantonio Raimondi (Italian, c. 1480–c. 1534), “Massacre of the Innocents,” c. 1513-15, 11″ x 16 1/4″, based on a drawing by Raphael. (There were two versions of this print. One of them–not this one–had a fir tree in the upper right corner.) (Photo by Scott Ponemone)

Ugo da Carpi, “Massacre of the Innocents,” 10 1/2″ x 16 1/6″, c. 1520-17, from four blocks, based on Raimondi’s engraving without the fir tree. (Photo by Scott Ponemone)

Seeing the Raimondi after 25 years living with Avery’s version was simply startling. I immediately felt compelled to contact Eric and ask him why he chose to do a huge Massacre and what changes he decided to make to the image. While he answered my email almost immediately, he requested I hold off on asking him questions until he had finished a semester teaching. He wrote me:

“I will love to be in conversation with you about the print, but here is my current situation. I leave Texas Thursday to be the 2019 Basler Chair of Excellence for the Integration of the Arts, Rhetoric and Science at ETSU [East Tennessee State University] in Johnson City, TN. I’m working on an exhibit–Epidemic–and teach two classes. The heart of the opiate epidemic is in Appalachia, and I’m working on what I call ‘Narrative Naloxone, Art for the Spirit,’ whatever that means.”

The semester ended with his Epidemic exhibition at ETSU’s Reece Museum.

With the semester over and finally having Avery’s attention, I thought I needed to talk to him not only about Massacre but also about his work as a physician/teacher. So this blog post will be divided into two parts: 1) about Avery the creator of Massacre of the Innocents and 2) Avery the “visual medical humanist,” to use his phrase (as exemplified by is work at ETSU). Or as his newer website (EricAveryArtist.com) states: “For forty years he has worked at the intersection of visual art and medicine, leaving the practice of medicine several times to concentrate on his art career.” (His Massacre print can be found on his older website–www.DocArt.com–in the print catalog for 1984.)

Massacre of the Innocents

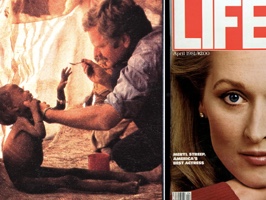

I asked Avery what was the impetus for creating his version of Massacre. He sent me this image from a 1980 Life magazine spread showing him in Somalia feeding an emaciated Somali refugee. In his email he said, “I had been working to save thousands of starving children in Somalia refugee camps and returned home to find the USA supporting and training soldiers who were using children as targets in El Salvador.

“I wanted to make a print about the slaughter of children and remembered my first encounter with Raimondi’s phenomenal print–my knees went weak looking at it–this doesn’t happen often.”

The slaughter of children, of course, was the topic of Raphael’s drawing that Raimondi used to make his engraving. In the book The Chiaroscuro Woodcut in Renaissance Italy (Delmonico Books, Prestel, New York, 2018), Naoko Takahatake, Curator of Prints and Drawings at the Los Angeles County Art Museum, wrote: “Raphael used contemporary Rome, with the Ponte Fabricio in the background, as the setting for the biblical episode in which Herod orders the execution of male infants in Bethlehem.”

In adapting the Raimondi, Avery had to make some decisions. He wrote, “His engraving is so small. I just gridded it; used gouache to put it onto my enlarged block 3’ x 6’. Then I tried to translate values into line structure. It’s a real fine linocut showing what sharp tools in my hands could do.”

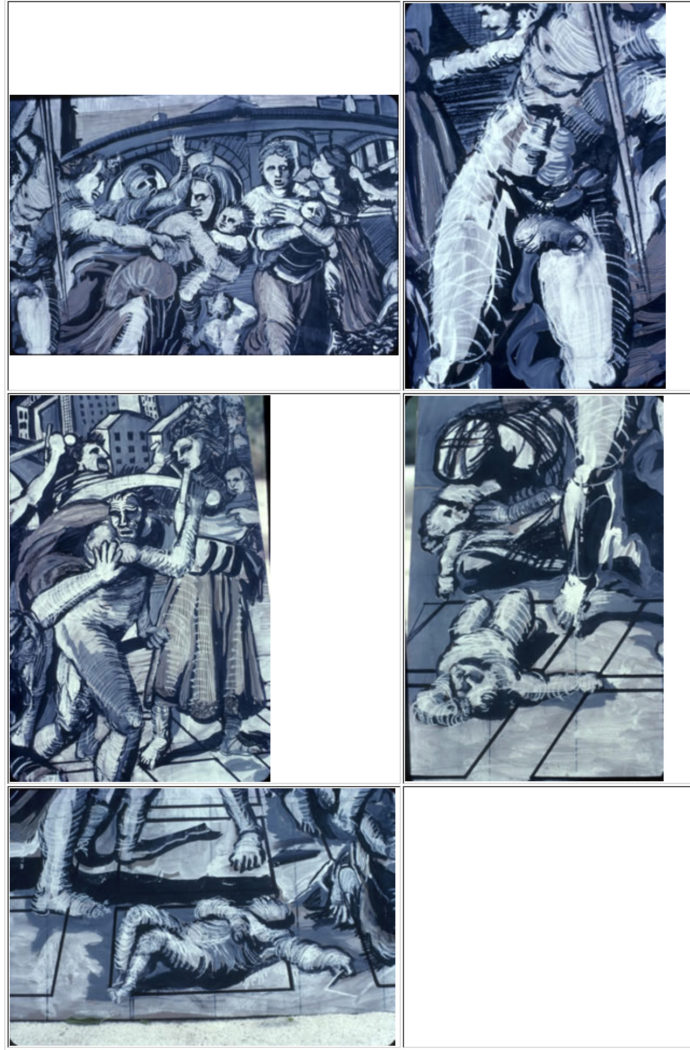

Details of Avery’s gouache for “Massacre” as shown on his website DocArt.com (Courtesy of Eric Avery)

In the process of enlarging (from 16 to 50 inches wide) Massacre and translating the engraving into a linocut, his reading of the Raimondi affected the decisions he needed to make. “I think Raimondi structured his print design to travel the viewer’s eye around in the print to phallic references,” he wrote. “The massacre was a sexual slaughter based on the penis.”

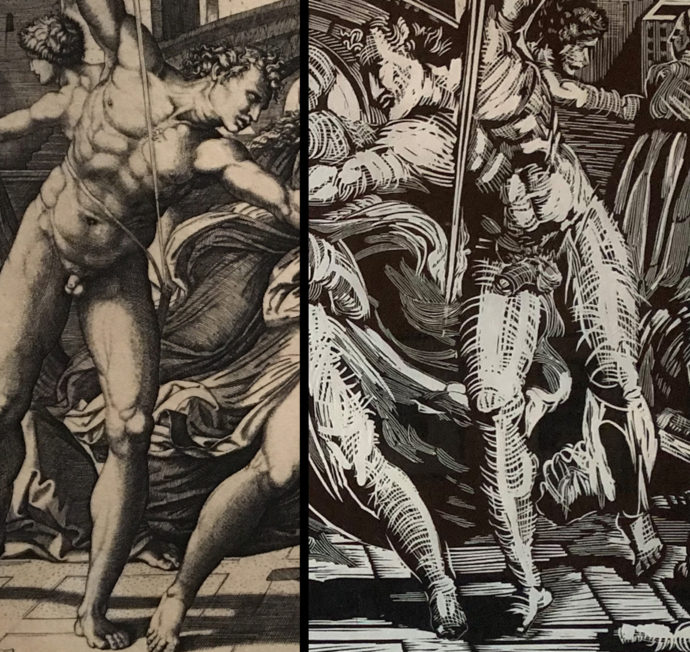

To emphasize the phallic references, Avery decided to reverse the left-right orientation of the Raimondi. (In other words, he did not reverse the Raimondi image when he created his linoleum block. As a result his Massacre print is reversed from the Raimondi.) Avery explained, “By reversing the position of the man with the sword, the viewers gaze moving from left to right encounters the assault. The sword stabs into the picture. This is mirrored by the penis swinging, like the sword, into the viewer’s gaze.”

He added, “This figure with sword swings into the movement into the slaughter. Sword is penis. Hand grabbing child leg is phallic.”

The Raimondi sword-wielding male nude (left) compared to the Avery version (right). (Image by Scott Ponemone)

Avery added, “I tried to increase the focus on Raimondi’s print. His circles the eye around the phallic representations of the slaughter. My artist friend here in San Ygnacio, TX, Michael Tracy, saw my gouache drawing on the lino and told me to redraw the penis and swing it out toward the viewer.” And Avery enlarged that penis as well.

The bridge in Avery’s Massacre is no longer the Ponte Fabricio. It represents the divide between Latin America and the United States. Avery wrote, “Left side North is the USA, slaughtering children in the South. I live on north bank [San Ygnacio] of the Rio Grande. Mexico would be on my geophysical right.”

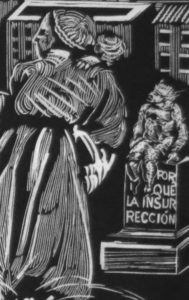

Below the buildings on the right, Avery said, “you might notice the figure sitting on a pedestal with text. The Spanish text is Porque La Insurrection. “Why the insurrection” (i.e. why the killing of the male children).

He explained his reference to “slaughtering children” by saying that in 1984 when making Massacre, “the Central American Wars ( El Salvador, Guatemala/Reagan administration/Oliver North etc) were raging. Children being massacred. Sancturary Movement was moving people across the Southern Border near my place.”

The little house on the bridge is his San Ygnacio studio across from the town water plant tanks.

“When I was in Mexico City during this time of learning about refugees in South Texas,” Avery wrote, “I visited Laura Bonaparte, a well known Argentinian human rights activist. . Her children and other family members had been disappeared by the Argentinian military. She was involved with Madres de Plaza de Mayo. I offered to give Laura any of my prints which I had with me to show her. She chose Massacre of the Innocents.

“I was flabbergasted because of what she had experienced. I asked how she could live with something that showed children being slaughtered. She was a psychoanalyst. She responded–and I’ve never forgotten her words–’Because it reminds me of what should not happen.’

“Prints about what is happening can remind us of what should not be happening. The work is done maieutically–a [Socratic] strategy used in the medical humanities. I’m a visual medical humanist. I began to grow this practice when I entered medical school from art school in 1974. The art world doesn’t give a shit about the medical humanities, but that is another more serious problem for another email.”

Epidemic at ETSU

East Tennessee State University was the second venue for Epidemic. The first was last year at York College, York, PA, where Adam DelMarcelle teaches. Epidemic was Adam’s idea. As Eric Avery recalled:

“He called me out of the blue [several years ago] then brought me to Lebanon College as a visiting artist to lecture, work with his students and we silk screened on green hospital sheets. That was our first collaboration

“He knows and respects my print work, used it to teach his printmaking students…. He had begun doing projections on buildings in Lebanon, PA, in response to his brother’s opiate overdose.

“He asked if he could use my arm woodcut–Blood Test 1986–for a projection. He photoshopped a syringe into my image. I said sure. He explained what he was trying to do with printmsking as social protest and asked if I wanted to work with him and exhibit at York College. I suggested he do a projection on a farm silo. Adam found an Amish farmer who agreed.”

In turn DelMarcelle in an email recalled, “I was exposed to Eric’s work when I was an undergraduate in the mid-90s. His ability to document in such direct, beautiful and terribly honest ways resonated with me even at 20 years of age. When I began to make work about the opioid epidemic, Eric’s work was thrust back to the forefront of my mind…. I reached out to him on late one night when I was having a hard time dealing with the work I was making. I sent him an email through his website never assuming he would return it. I told him how much his work meant to me and that I would love to talk to him about a potential collaboration. I shared my story with him and how I was trying to find out how you can work from a place of direct trauma with out killing yourself in the process. A few days later I received an email from him, and a few weeks after this we met in person.”

DelMarcelle said he had become an arts activist because “my brother died of a heroin overdose and this changed my life forever. In my loss and grief I made work to document my family’s experience. Through this process I uncovered major injustice in my hometown which I took on head on. This led to me traveling nationally making work on this topic educating students to their societal obligation to their communities through their documentation and making.”

Epidemic came about, DelMarcelle said, when he was offered an exhibition of his work at York College. He said he “was asked by the curator if I could show with any artist to compliment my work who would it be. Eric was the only one I wanted to do this with. This invitation morphed into Eric and I starting on a mission that is so much more than an exhibition of pictures on a wall. When I agreed to show my work at York, it was with the stipulation that they needed to commit to educating the community through our time there.

“We built a harm-reduction, art-medicine action space in the middle of the gallery that could be used by the harm-reduction community for art actions. We used the gallery and museum space in a subversive way to get the viewer to get closer to a topic they would never allow themselves to get close too, addiction and addiction stigma. Each week we held a different experience including Naloxone trainings, needle exchange, folks in recovery speaking and meetings for folks that have lost loved ones to substance use disorder.”

DelMarcelle did most of the curating of Epidemic at York College, but, he said, “At ETSU Eric was in residence which allowed him to take the lead. He did so many wonderful things while there, and the community of Johnson City and Elizabethton were lucky to have him, and I know he feels the same about them. Eric and I trust each other fully which allows this collaboration to work so perfectly.”

Avery said, “There are a set of expectations attached to the semester long Basler Chair position. I taught two classes in the Art Department, gave several public presentations at the university and at the Quillen College of Medicine [at ETSU]. My two classes were Expanding the Boundaries of the Relief Print and Visual Communication and the Opiate Crisis. I involved the opiate class students and their art work in the exhibition.”

He called Epidemic as presented at ETSU’s Reece Museum “my most complicated art medicine project.” He said his focus was on humanity’s responses to the opiate epidemic, which is particularly severe in Appalachia. To emphasize this a count-up clock was created. It would record each opiate death that would occur during the run of the exhibition. Avery said, “It was turned on when we opened the exhibit April 15. Every 8 minutes someone dies of opiates in the USA. When I unplugged the clock May 31 at 4 pm [the number reached] 8030 deaths.” To stress one of the consequences of the epidemic, he remarked, “Every 24 minutes in the USA a child is born with neonatal opiate abstinence syndrome.”

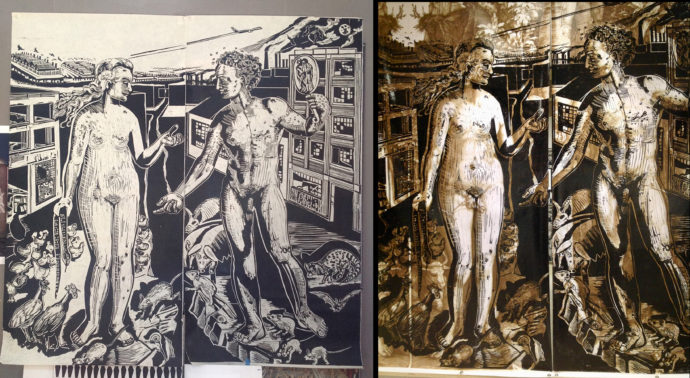

Three 6′ x 6′ pairs of Avery’s “Paradise Lost” were hung at ETSU’s Reece Museum. (Courtesy of Eric Avery)

Opposite the clock hung three banners based on Albrecht Dürer’s famous 1504 engraving of Adam and Eve. (Once again Avery reversed the engraving’s right-left orientation.) The area in front of the banners was called the Harm Reduction Space, which, Avery said, was used for “training on use of Naloxone and several public conversations with physicians providing Medication Assisted Treatment and care for babies with Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome. Another was with the person who ran the Syringe Exchange project.”

For the banners Avery adapted his 2010 print Paradise Lost, a pair of 3′ x 6′ linocuts. As stated in Avery’s website, he had appropriated the Dürer to illustrate the “14 major inflections of Adam and Eve.” In Avery’s print “they are surrounded by multiple reservoirs for infectious diseases: chickens, pigs, rats, bats and a civet. Vectors for infectious diseases: fleas, ticks, mosquitoes and flies are attracted to them.” He noted in an email: “Eve has no apple; she is holding a dead snake.” Due to misalignment, the ear from Dürer’s Eve appears in the cheek of Avery’s Eve.

Avery’s original “‘Paradise Lost” linocut (left) with the pair used at ETSU (right). The amber tone is the enlarged Dürer image printed on vinyl. (Courtesy of Eric Avery)

For Epidemic he printed the Paradise Lost linocuts over the Dürer image, which was first printed on vinyl banners. (To get the two images to sort of line up, Avery had the Dürer reversed left-right.) “This reprinting over the Dürer,” he said, “is much better. For the vinyl banner, the sides of the print had to be mirrored to widen the banner to fit the block. Upper left corner shows this best.”

Body Maps surround students listening to Adam DelMarselle (black cap) in the Epidemic exhibition. (Courtesy of Eric Avery)

“About community involvement and the Epidemic exhibit,” Avery said, “I did two Body Map workshops at Red Legacy, a project for women in recovery. Visitors to exhibit walked through these life-sized body maps.”

Eric explained that he knew about body mapping from his HIV days. While an online definition of body mapping calls it “a form of art and narrative therapy” in which individuals create an image of their body, Eric wrote that, when he worked with the women of Red Legacy, “the goal was not art therapy. I am not an art therapist. The goal was to just have fun with paint, oil pastels. It was process not product.

“The women ended up making pictures about themselves. One or two of my ETSU students were with me. Our role was to stay outside what the women were doing, explaining things like yellow plus blue makes green, thinning colors, brushes to use, covering up brown paper with color as background…. After about three hours, each women put their map up on a wall and translated or told their stories. Later when I began to plan the exhibition, I asked if they would let me include their maps in the exhibit.

“One of the great successes of the exhibit was the displaying of these beautiful paintings. The women came to the reception with their children. It all had a great affirming effect on the women. Their courage and resilience was on display.”

“My visual communication class students,” Avery said, “made graphics for a trailer that will be used by the Carter County Drug Prevention Project as a teaching space. My studio assistant Adam Case Leestma made a scale model of the trailer to be used to raise money to turn the trailer into a teaching space. The students scaled down their graphics for the model. The hole in the pedestal is for donations collected for the project.”

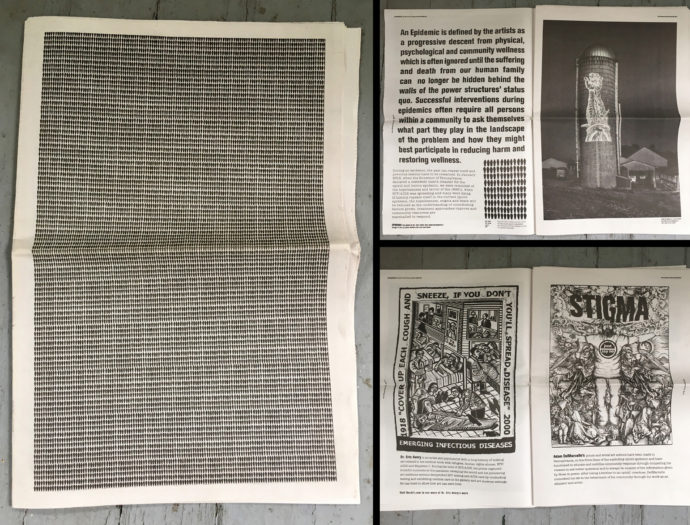

Coffins cover the front (left) of the exhibition catalog. Right are two spreads from inside of the catalog. (Courtesy of Eric Avery)

When I asked about the catalog of Epidemic, Avery said, “It’s not a picture catalog but an informational resource. Cover: 40,000 coffins = 2017 US opiate overdoses. An interior two-page spread [has coffins representing] 400,000 opiate deaths since OxyContin was introduced by Purdue Pharma in 1996.”

Adam DelMarcelle screenprints coffins for “Epidemic” as Eric Avery looks on. (Courtesy of Eric Avery)

Comparing the two Epidemic venues, DelMarcelle wrote, “In York we aimed to support local harm reduction and educate as many students as possible. In Tennessee we were welcomed much more dearly into the Johnson City and Elizabethton recovery communities because Eric was living there and he has an unbelievable way of connecting to others. The amount of events Eric had going on in the Reece Museum each week was amazing and by the end of the exhibition we had lots of community groups using the space for their activities.

Next, he said, “Epidemic goes to Brooklyn next at City Tech College [New York City College of Technology]. They are interested in engaging their entire campus with our work. Some exciting possibilities in the works. I think it would be powerful for a large museum to take on this project as well (Philadelphia Museum of Art or the like) and show a commitment to this type of work. Museums are not meant to be vacation destinations; they are educational institutions. While you spend time viewing, outside these sterile walls the world is crumbling. We must use our time viewing to form better questions of ourselves to take back into the world with us. If we do this, we may just find some answers.”

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/eric-avery-doctor-of-printmaking/trackback/