Arieh Allweil’s Haggadahs: Part 1

Introduction

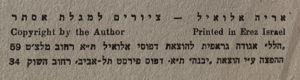

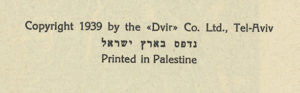

When I began working with Ruth Sperling and Nava Rosenfeld, the daughters of artist Ariel Allweil ( 1901-1967), in the summer of 2020, we introduced readers of my ART I SEE blog to the books and portfolios created by Allweil from 1924 to 1949. (LINK) At the end of that post was a sequence of boxes, one for each publication. The last box mentioned The Chapters for Passover Celebrations, 1948 (the middle image above), and the IDF Passover Haggadah, 1949 (the image on the left). Missing from that initial presentation was the Haggadah for Passover (on the right).

(Also missing was Allweil’s fourth Haggadah, first published in 1954, in which images of 17 of his oil paintings are tipped in. His daughters refer to it as the “painted Haggadah.” Since it’s the only one that the artist did not illustrate with either linocuts or lithographs, it’s visually quite separate from his first three Haggadot (plural for Haggadah).

Neither daughter mentioned Haggadah for Passover in 2020. I learned about when an Israeli seller posted a copy of it on eBay this year. and I purchased it. When I asked Sperling about it, she wrote in an email: “We did not add it to the first Allweil blog, because our father did not discuss it with us.” She added, “The copy I have, I got it from a friend who inherited it from a painter friend of our father.”

The second line reads: “All rights reserved to Alexander Moses.” The third line gives the address of this publisher. To learn more about Moses, Sperling consulted Shalom Sabar, Professor Emeritus from the Department of Art History and Department of Folklore at Hebrew University of Jerusalem, who told her that A. Moses printed five Haggadot and that her father’s was the fourth. He told her that that information came from “Haggadah Thesaurus” (“Otzar Ha’Haggadot”), a bibliography of Passover Haggadot edited by Isaac Yudlov.

Her friend Sarai Tzafrir, who was a librarian at the National Library, also told her about that bibliography. So Sperling went to the library hoping to find more. She said she “consulted with Dr. Hezi Amior, the curator of Israeli Art at the National Library, who said the date given at the National Library is 1940, meaning from 1940.”

Sperling wrote: “I think this date [1940] is about right because every book of my father, from Amos, published in 1940, on, had images reflecting the disasters of World War II, and later the Holocaust, and especially in the Haggadah for Passover.”

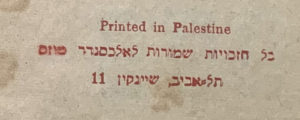

The phrase “Printed in Palestine” in the colophon (above) also helps date the publication. Sperling noted that that phrase was an indication that the Haggadah was published early in the 1940s, because Jews in the British Mandatory Palestine (1920-1948) were openly using the words “Printed in Eretz Israel” soon after.

For the first edition of his Scroll of Ruth in 1939, the colophon (left) also reads in English “Print in Palestine,” but the Hebrew (נדפס בארץ ישראל) directly above those words read: “Printed in Eretz Israel.” The colophon in his 1939 book Anonymous Jew and his 1940 Book of Amos also has “Printed in Palestine” in English and “Printed in Eretz Israel” in Hebrew. The wording was not changed when the second edition of Amos was published in 1941.

Then his 1942 book Scroll of Esther states in English “Printed in Erez Israel.” The colophon in his 1943 Scroll of Lamentation has a similar presentation. So does the second edition of Scroll of Ruth from 1943-44. Sperling wrote that Professor Sabar “was not sure there was a specific date when ‘Printed in Eretz Israel’ was used globally in Hebrew and English.”

Then his 1942 book Scroll of Esther states in English “Printed in Erez Israel.” The colophon in his 1943 Scroll of Lamentation has a similar presentation. So does the second edition of Scroll of Ruth from 1943-44. Sperling wrote that Professor Sabar “was not sure there was a specific date when ‘Printed in Eretz Israel’ was used globally in Hebrew and English.”

But if the use of “Eretz Israel” in English on colophons of Allweil’s books is a useful indicator, his Haggadah for Passover was published before 1942.

I also asked the daughters if their father read from his Haggadah for Passover during Seders. Sperling replied: “As to your question which Haggadah was used at home in the 1940s, at the beginning of the 1940s I was too young to remember, and these were war years. Also, in the 1940s and 50s we used to have big Seders at our grandfather’s home (my mother’s father Dr. Haim Bograchov), and I don’t remember which Haggadah we used in the 40s.”

Another way of dating Haggadah for Passover would be a look at stylistic changes to how he cut the linocuts that he used to illustrate all of his books that I’ve mentioned.

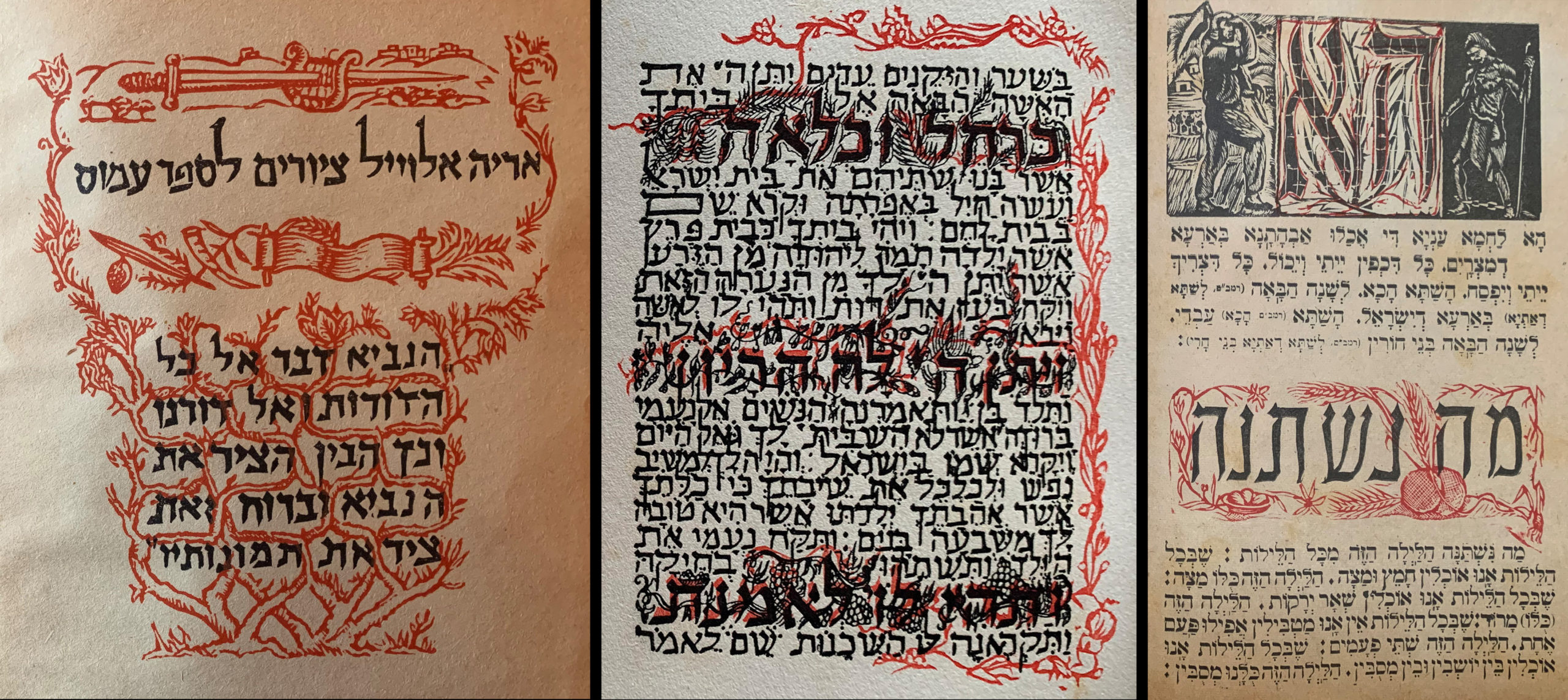

On the far left is a plate from Scroll of Ruth. This linocut is broadly cut with little indication (small parallel lines) of tone. The same cutting is found in his Anonymous Jew (also 1939) and from his From a Tour of the Land (first edition in 1939). Next to it is a plate from Allweil’s Book of Amos, 1940. Here the artist has added many marks to indicate tone (or shading), although the cutting tends to disorganized as if the artist is finding his way. Then the next plate (second from the right) is from his 1942 Scroll of Esther. Here the marks to indicate tone are much more uniform, often in a series of parallel cuts. On the far right is a plate from the Haggadah for Passover. It’s cutting shows the same sophistication as that illustrated in the Scroll of Esther image.

I believe these images show a progression in Allweil’s linocut skills and intensions. I doubt that he could have cut that Haggadah for Passover plate before he made the Scroll of Ruth one. Nor do I think he could have made the Book of Amos plate after he made either the Scroll of Esther plate or the Haggadah for Passover plate.

Then if you consider the colophons between the use of “Printed in Palestine” found in Haggadah for Passover and the “Printed in Eretz Israel” found in Scroll of Esther published in 1942, it makes sense to suggest that Haggadah for Passover was published in 1941.

Another way of dating would be looking Allweil’s use of red ink.

Allweil didn’t print of his books with linocut blocks in red until the 1941 second edition of Book of Amos. Even then he added red only to the title page and (left) on the page opposite the title page. The 1939 first edition of Scroll of Ruth was only printed in black. But in his 1943/44 second edition of Ruth (middle) he added linocuts and printed them in red. The plate (right) is from his Haggadah for Passover. I picked a page that also has a vegetation motif in red.

I suspect Haggadah for Passover, which I believe only had one edition, was Allweil’s first book that was designed to incorporate red-printed linocuts. Then in 1942 came Scroll of Esther with red-printed linocuts. His most liberal use of red came with the second edition of Ruth. The 1943 Scroll of Lamentations, however, had no use of red except on the title page and book cover.

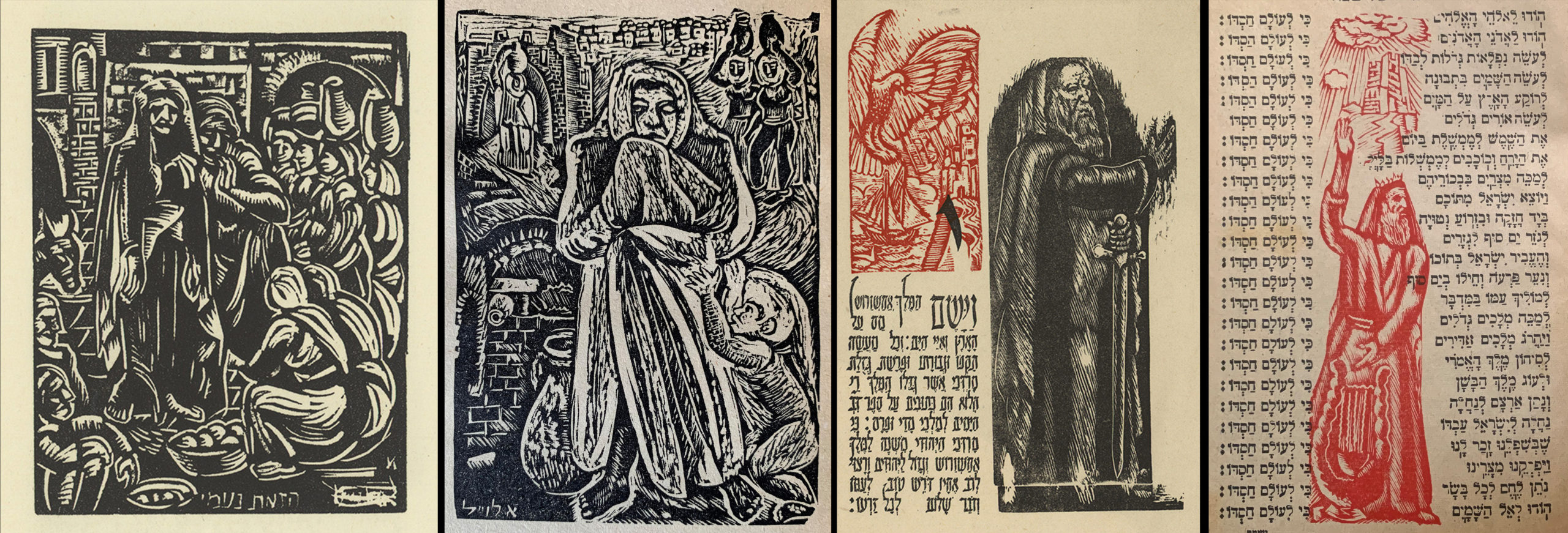

Drawings for Haggadah for Passover

Nava Rosenfeld was able to locate a few drawings that her father made for this Haggadah. I was able to match most up to pages in Haggadah for Passover.

On top are linocuts across a two-page spread that appears early in the book. Of the drawings below, note that the scythe carrier on the right and the beating scene in the middle are in reverse of the final left-right orientation while the drawing of the man in bondage is not.

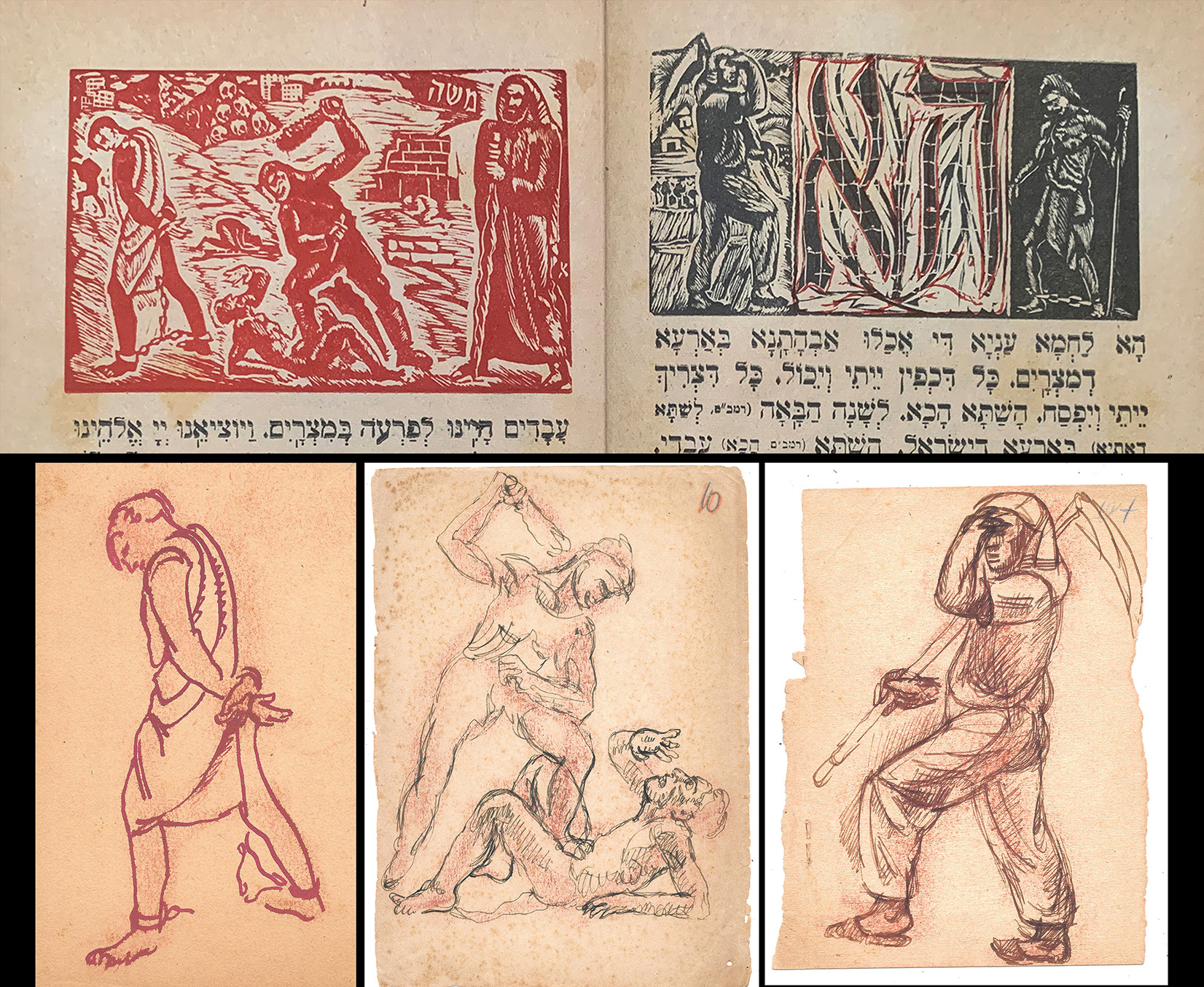

The drawing of the drinker (in the top row) relates to the first of ten plagues: Blood. See the reversal of his image in the top right of the black-printed linocut. The drawing of Moses (below) holding the Ten Commandments refers to the middle figure in the red linocut, which Allweil made to illustrate the song “Who Knows One?”

Allweil’s Haggadah for Passover

I’ve photographed most of the page spreads of Haggadah for Passover and Allweil’s daughter Nava Rosenfeld has graciously provided translations of the title page, the colophon, enlarged Hebrew words, image captions, and some important phrases of the text.

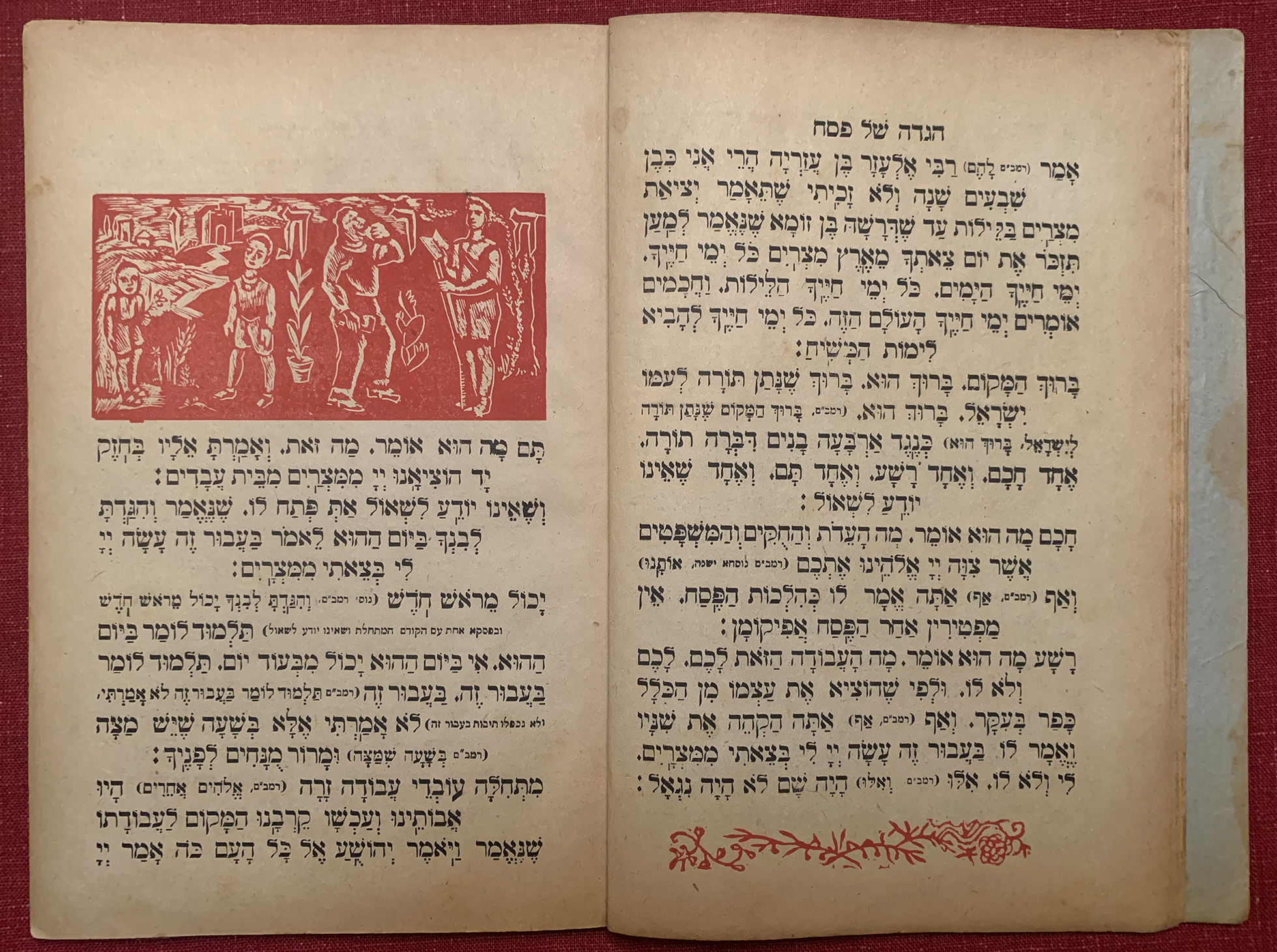

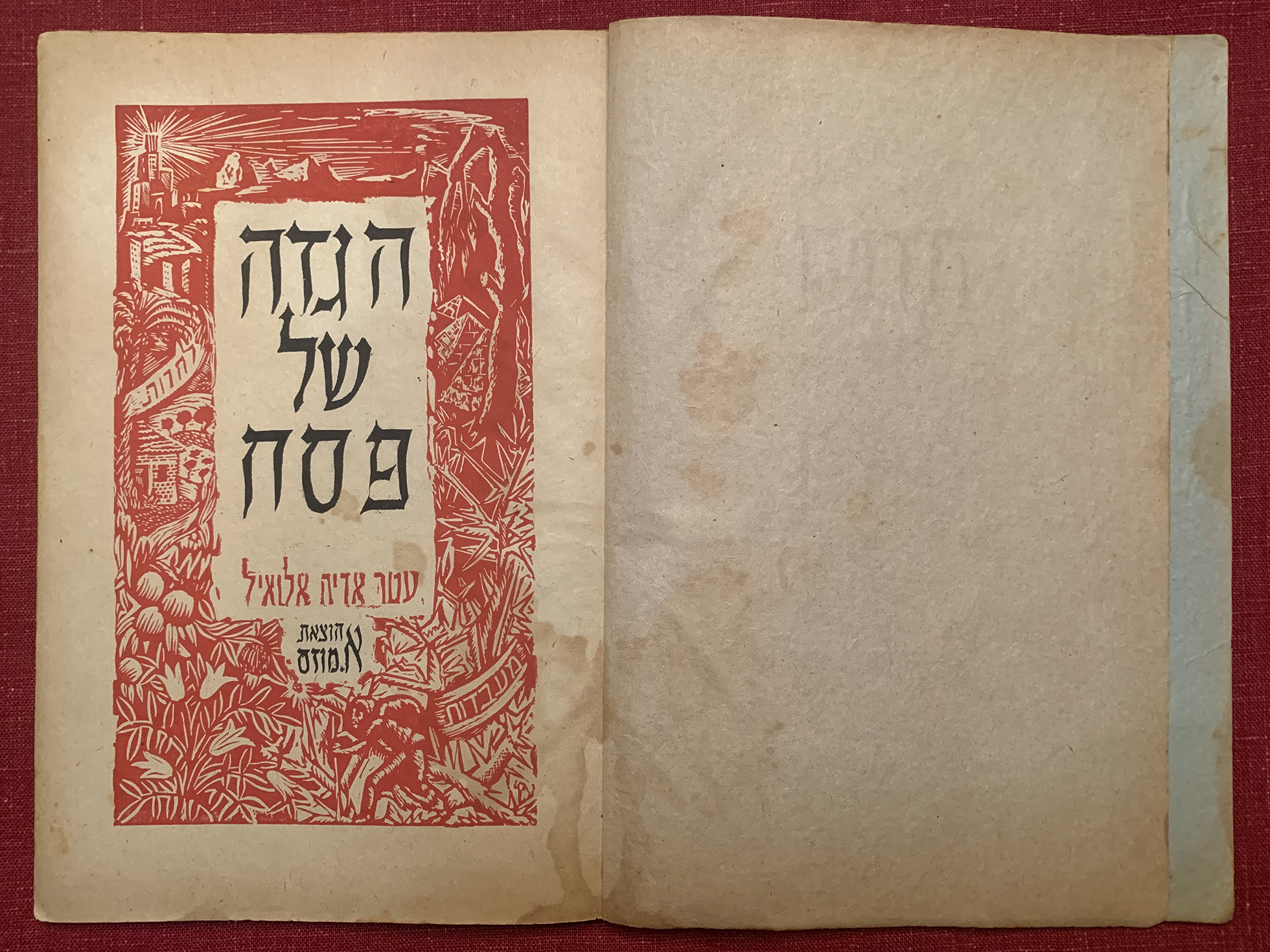

(black letters) Haggadah of Passover הגדה של פסח

(red Letters) Illustrations by Arieh Allweil עטר אריה אלואיל

(black letters) Publisher A. Moses הוצאת א. מוזס

(lettering cut into the border imagery) From slavery מעבדות (on the right); to freedom לחרות (on the left)

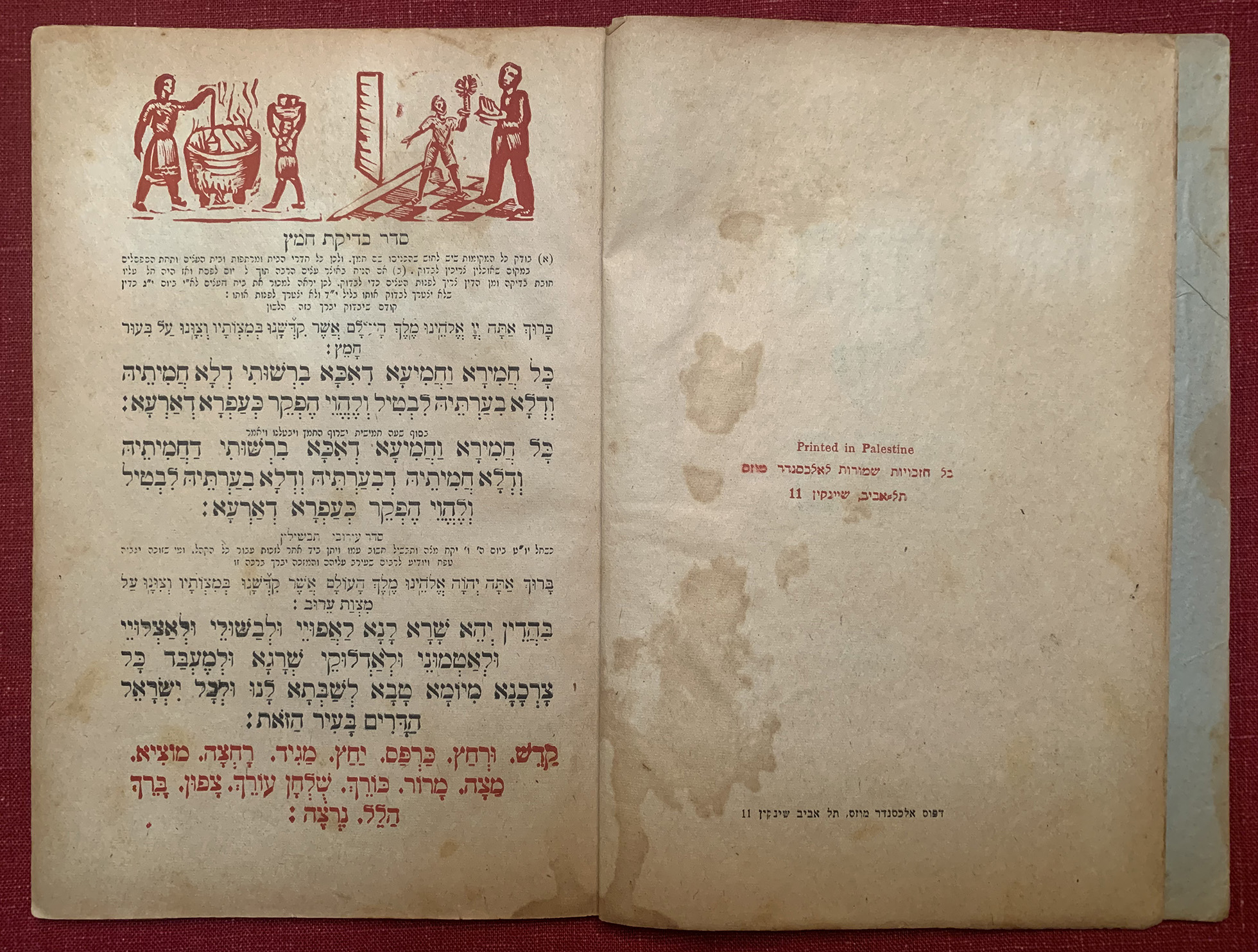

RIGHT: Printed in Palestine

All rights reserved to Alexander Moses

Tel Aviv 11 Shenkin St.

LEFT, caption: Removing the leaven סדר בדיקת חמץ

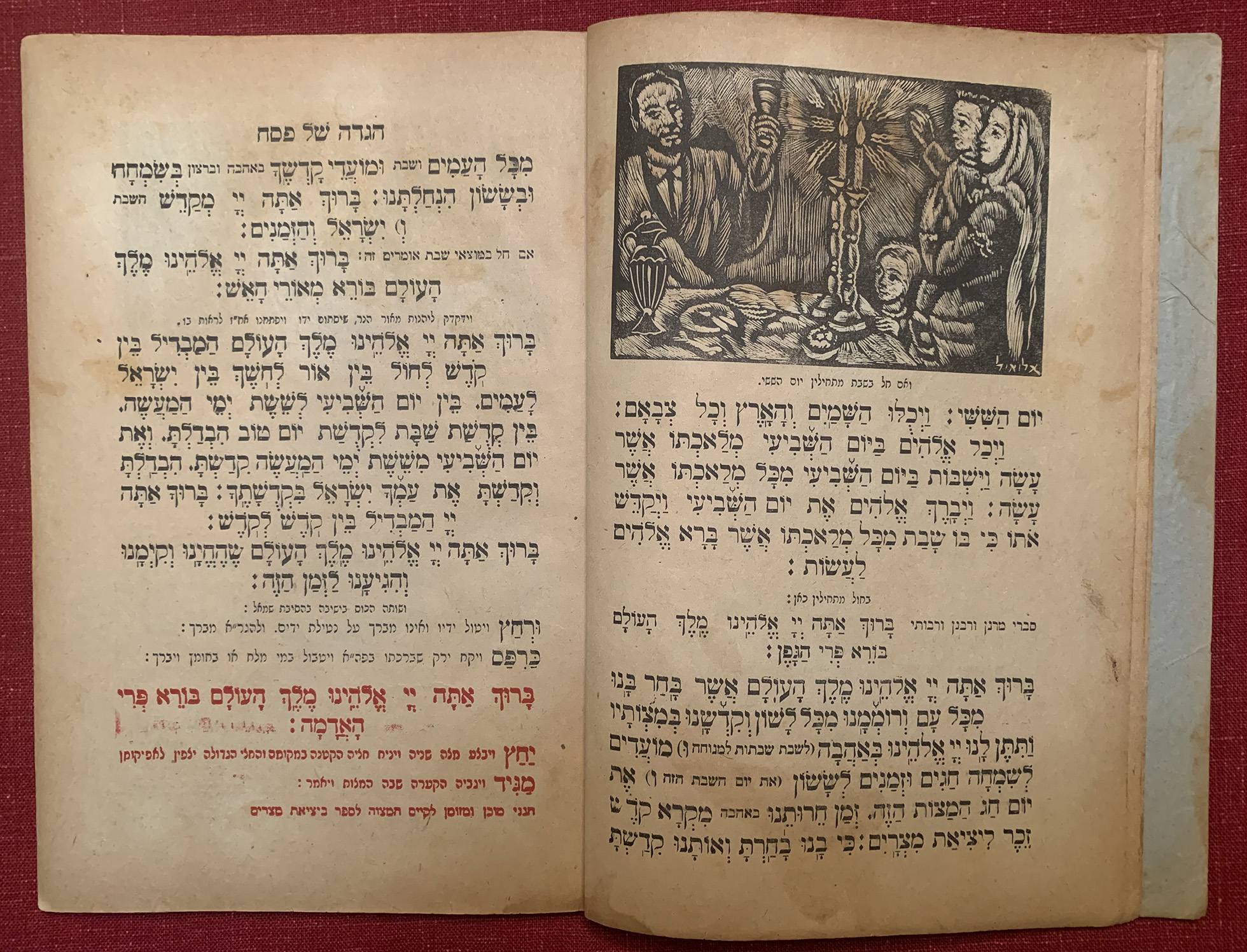

RIGHT: If the feast happens on the Sabbath eve, start with “Yom Hashishi and the heavens and the Earth were finished,and (on Friday: the sixth day) “All their hosts.”

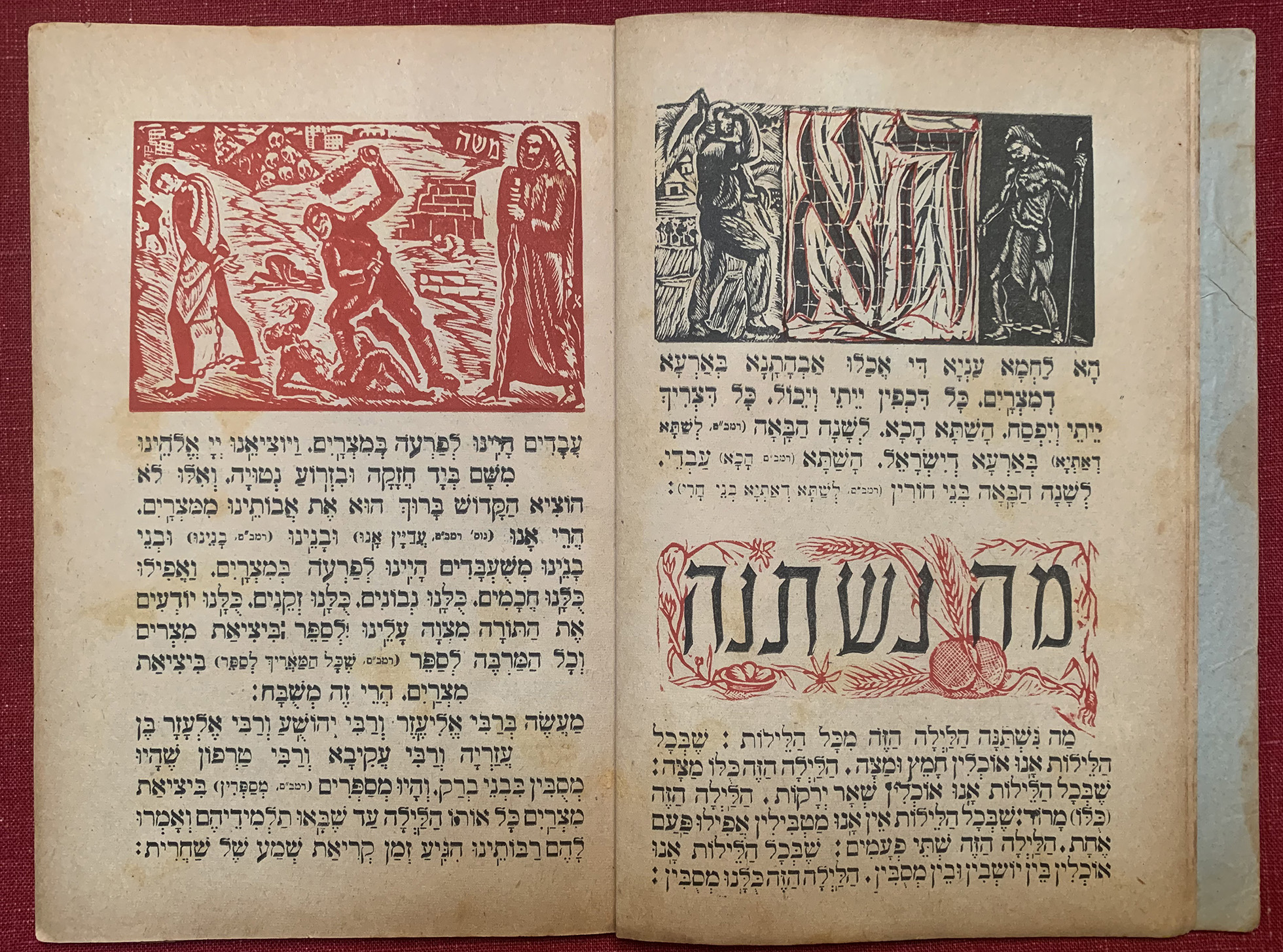

RIGHT: “Ha Lachma” הא This is the bread of affliction

“Ma Nishtana” מה נשתנה Wherefore this night distinguished from all other nights

LEFT, beginning of text: Because we were slaves into Pharaoh in Egypt and the Eternal, our God, brought us forth with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm. עבדים היינו

(In the red block) Moses משה

LEFT: In the image of The Four Sons (בנים) are letters representing each son:

LEFT: In the image of The Four Sons (בנים) are letters representing each son:

Chacham, the Wise ח

Rasha, the Wicked ר

Tam, the Simple ת

And, he who had no capacity in inquire ו

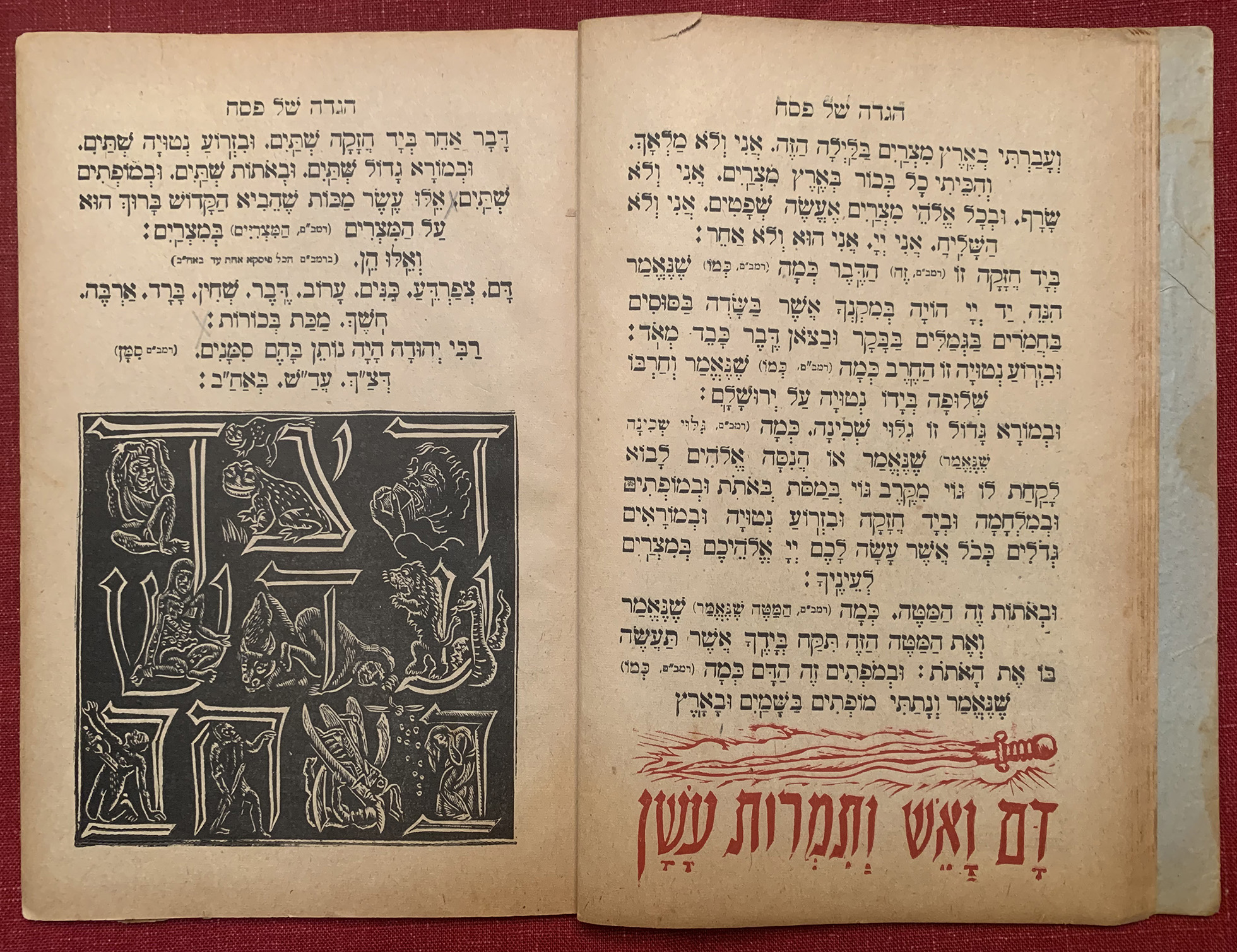

RIGHT: And fire and pillars of smoke and blood דם ואש ותמרות עשן

LEFT: These are the 10 plaques which the most holy, blessed be he, brought upon the Egyptians, and these are:

Blood (ד (דם

Frog (צ (צפרדע

Vermin (כ (כינים

A Mixture of Noxious Beasts (ע (ערוב

Pestilence (ד (דבר

Boils ( ש (שחין

Hail (ב (ברד

Locusts (א (ארבה

Darkness (ח (חשך

Slaying of the First Born ( מ (מכת בכורות

Three words in the illustration on the left

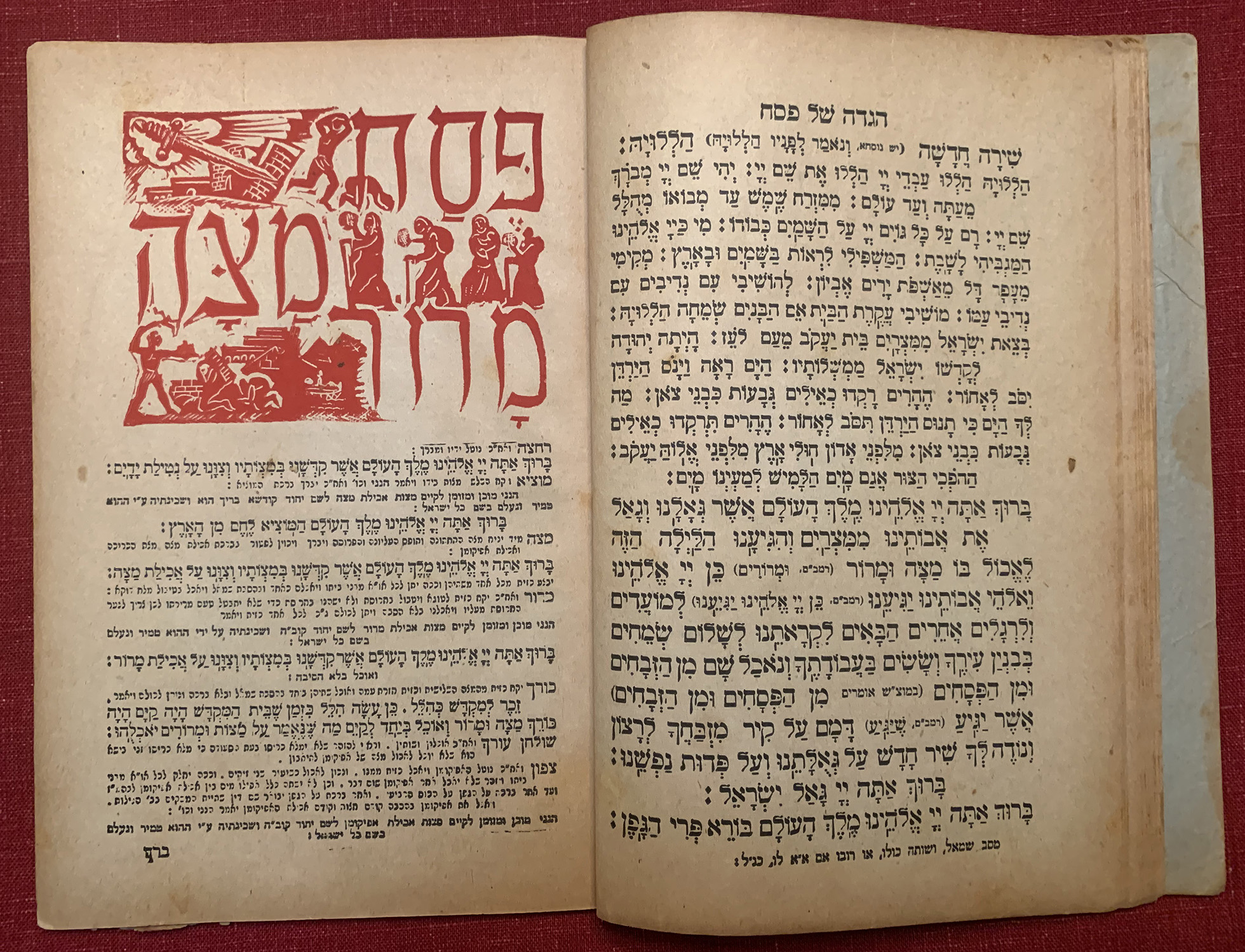

Pessach פסח

The Paschal lamb which our ancestors ate during the existence of the holy temple. Why was it eaten? Because the holy, blessed be He, passed over our ancestors’ houses in Egypt and spare our houses.

Matsa מצה

The leavened cake which we now eat. What does it signify? Because the dough of our ancestors had no time to become leavened.

Maror מרור

This bitter herb. Why do we eat it? Because the Egyptians embittered the lives of our ancestors in Egypt.

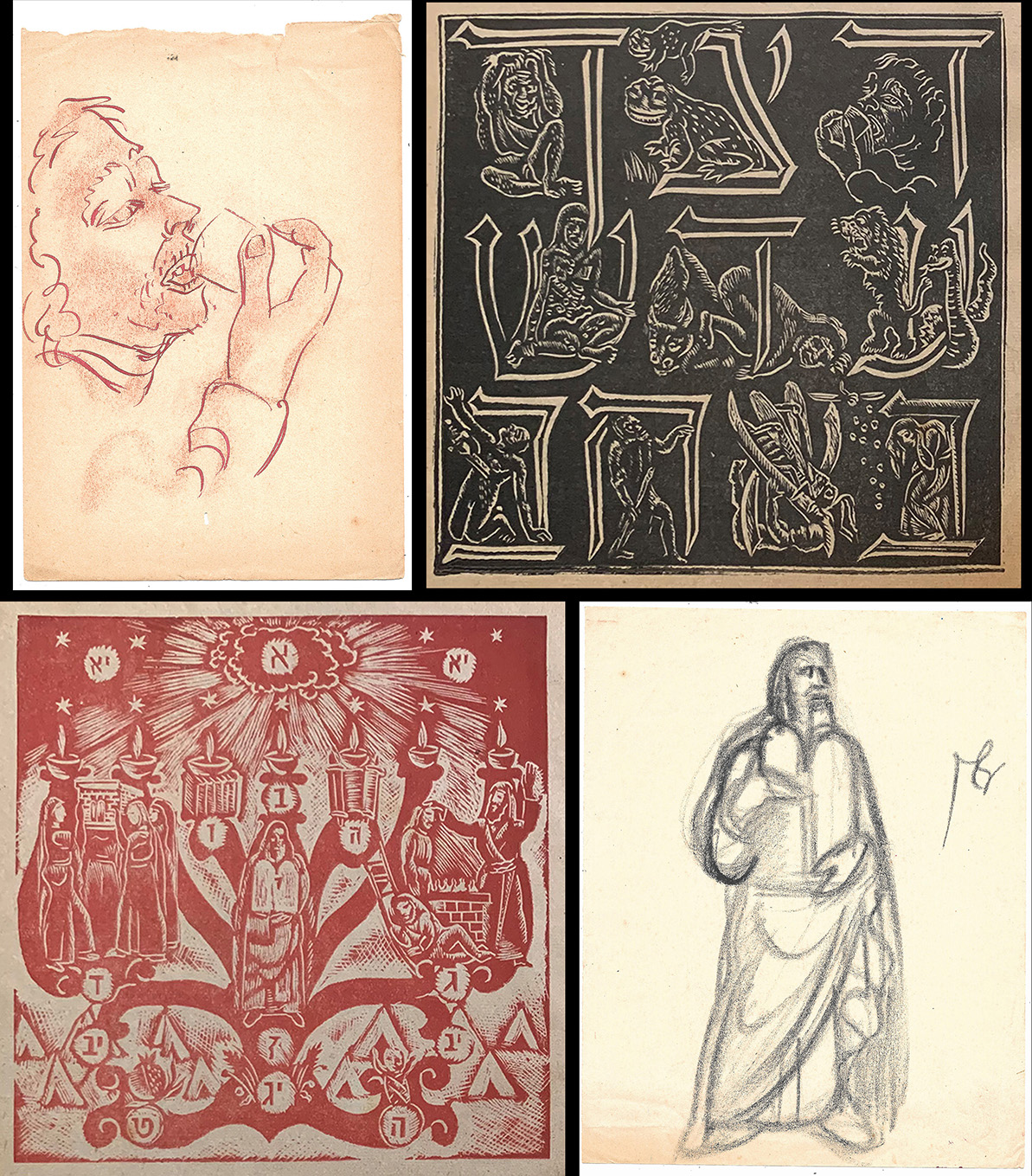

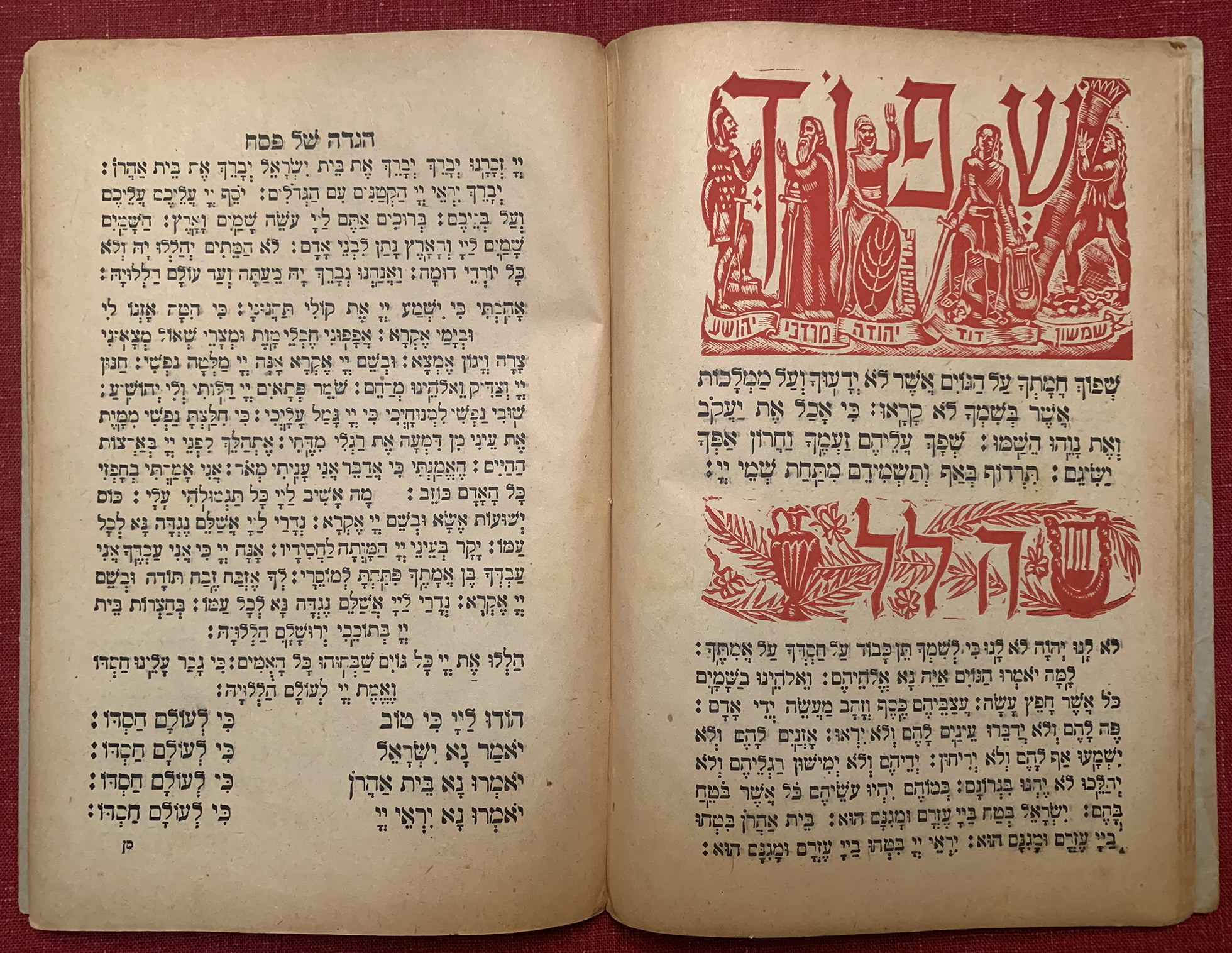

(Top right linocut, large letters) Pour out thy wrath upon the heathen who know not and upon the kingdoms who invoke the name. שפוך

(Small names under the figures) Samson שמשון, David דוד, Judah יהודה, Mordechai מרדכי, Joshua יהושע

(The word in the lower linocut) Hallel הלל

The Hallel Psalm: Not unto us, not unto us but into thy name give glory for thy mercy and truth’s sake.

הודו לה’ כי טוב

תהילים קל”ו

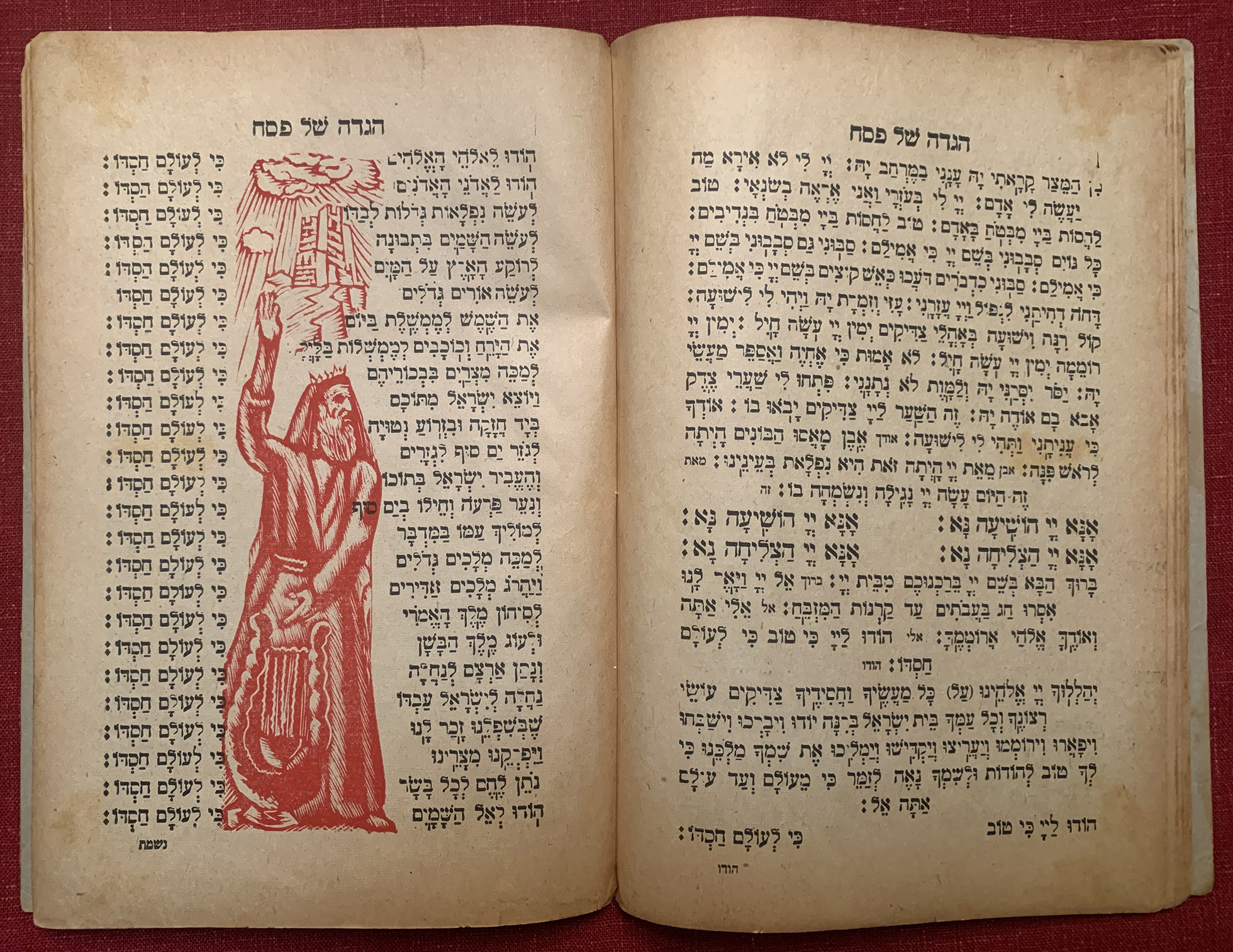

O Give thanks unto the Lord, for he is God; for his mercy endureth forever (Psalm 136)

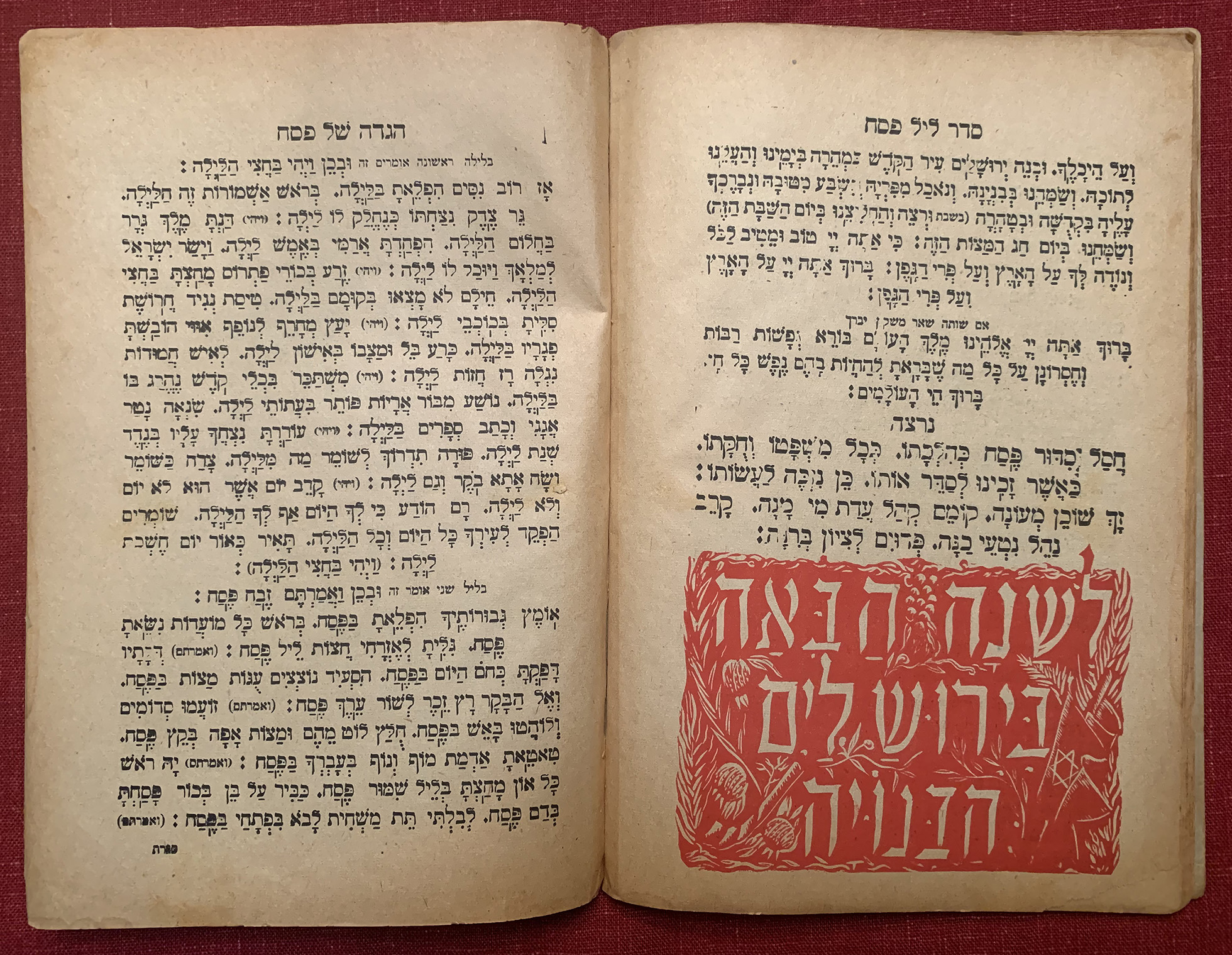

(Words in red linocut) לשנה הבאה בירושלים הבנויה

For next year in built Jerusalem

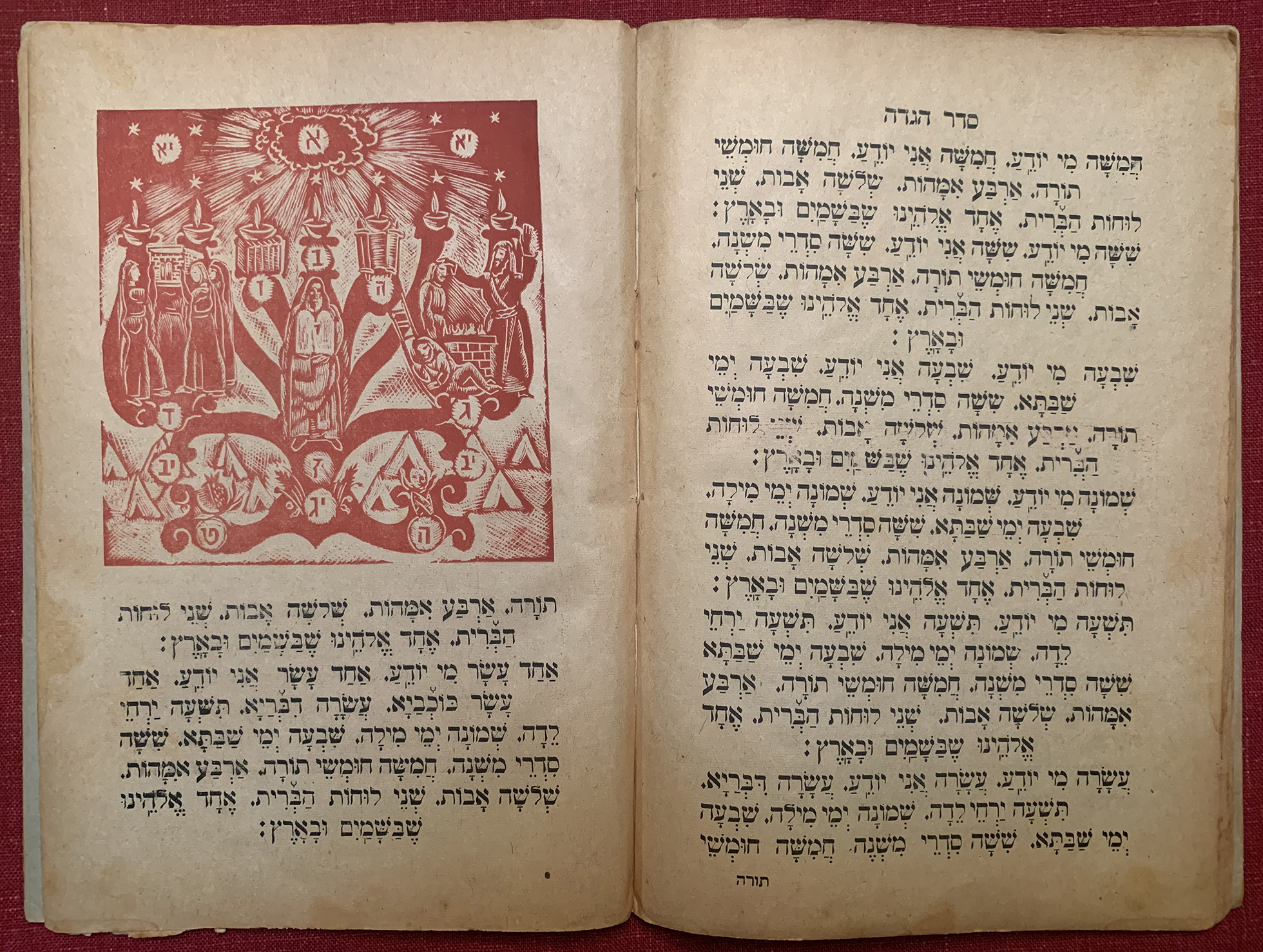

אחד מי יודע

Who knows one? I know one, one is the eternal who is above heaven and earth (a song)

The letters (Hebrew numbers 1 through 13) in the image refers to all that is spoken in the song:

א The God Eternal

ב The two tablets of the Covenant

ג The Fathers of three Patriarchs

ד The four matrons (mothers)

ה Five books of law

ן Six books of Mishna

ז Seven days of the week

ח Eight days after birth for circumsicion

ט Nine months presiding child birth

י The Ten Commandments

י”א Eleven stars

י”ב The twelve tribes

י”ג Thirteen divine attributes

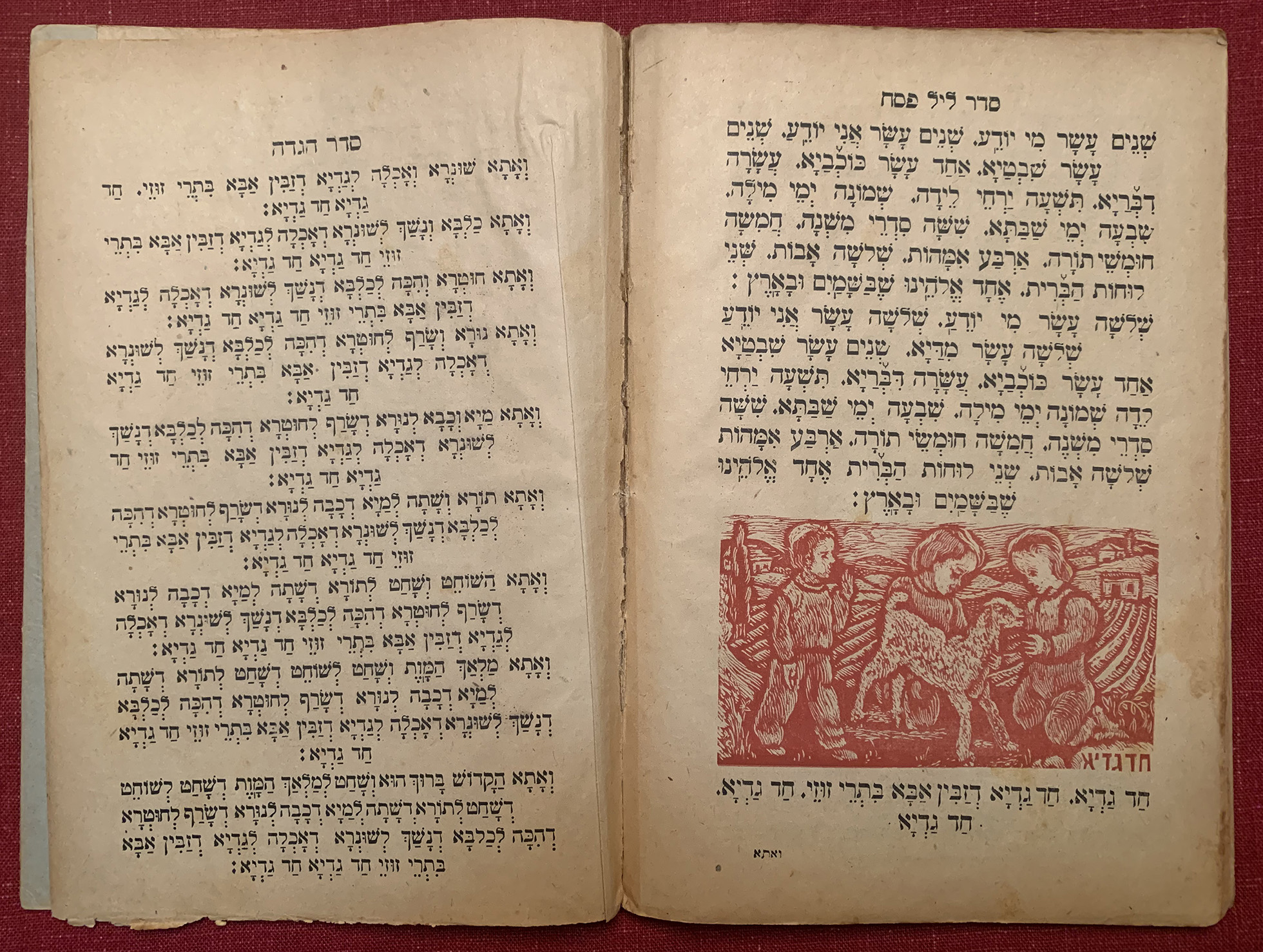

Only one kid that my father bought for two zuzim. חד גדיא

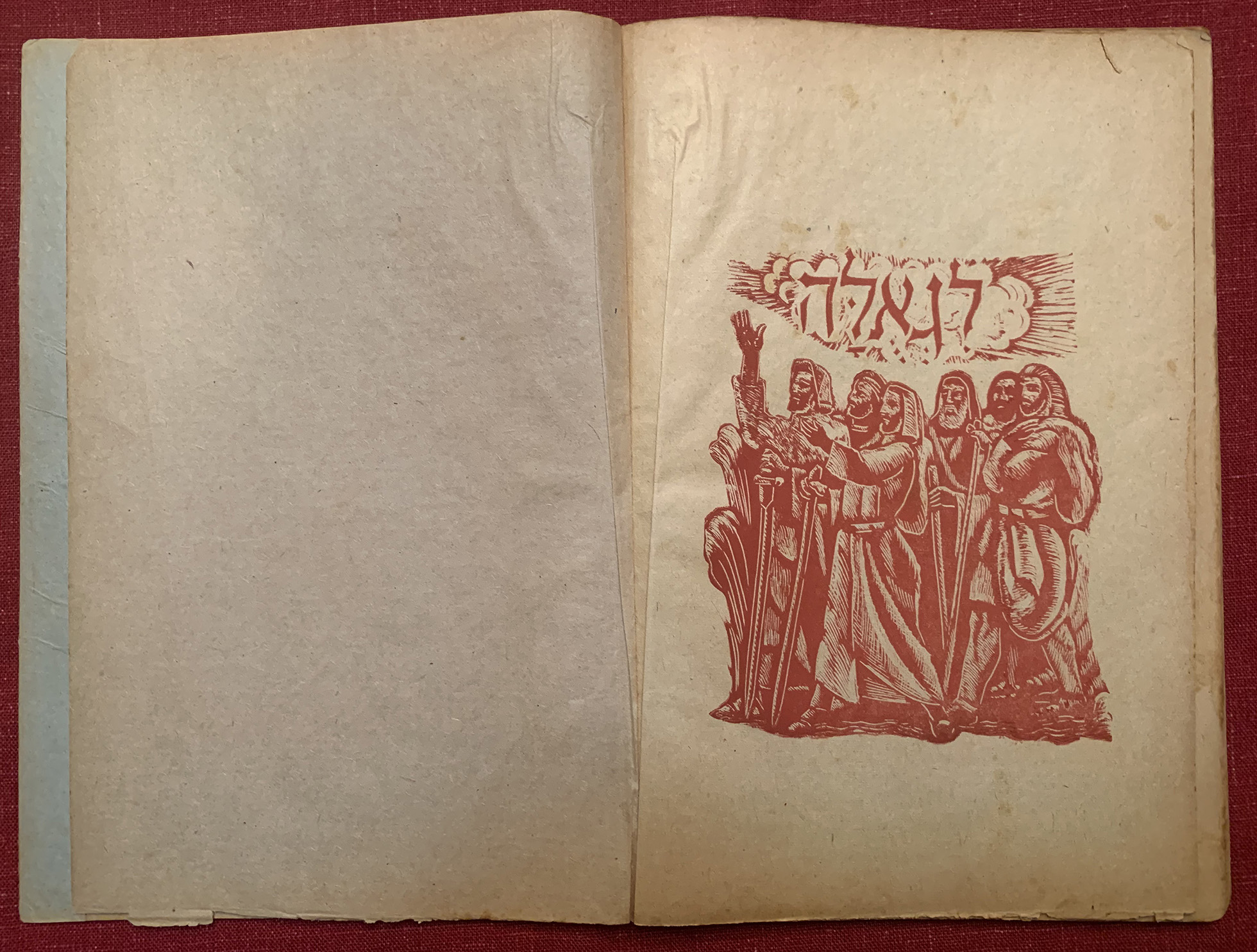

The Redemption. לגאולה

TO COME

I plan to cover Allweil’s other Haggadot in future ART I SEE posts.

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/arieh-allweils-haggadahs-part-1/trackback/

Pingback: Arieh Allweil’s IDF Haggadah