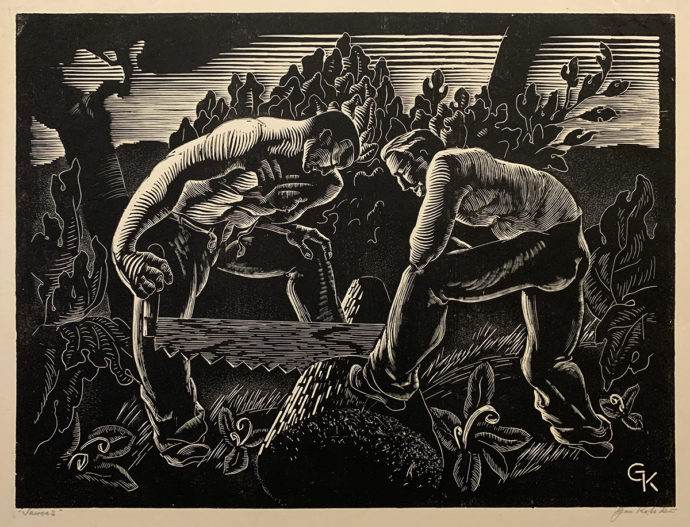

We traveled together to the 2019 Capital Print Fair when I came upon this print. I didn’t feel comfortable spending money at the time, but my friend and fellow Amherst College alumnus desired gifts to mark two upcoming weddings. So we agreed that I would paint two watercolors for him in exchange for him buying this print for me.

These are the two wedding gifts that I made to complete the exchange. Each shows the right hands of the betrothed couple touching at the tip of their thumbs. The border designs with the footprints of the Hindu Goddess Lakshmi derived from the Aipan folk painting tradition of Uttarakhand, India, where I had an artist residency in early 2016. (I posted on lessons in Aipan painting at http://www.scottponemone.com/lessons-in-aipan/)

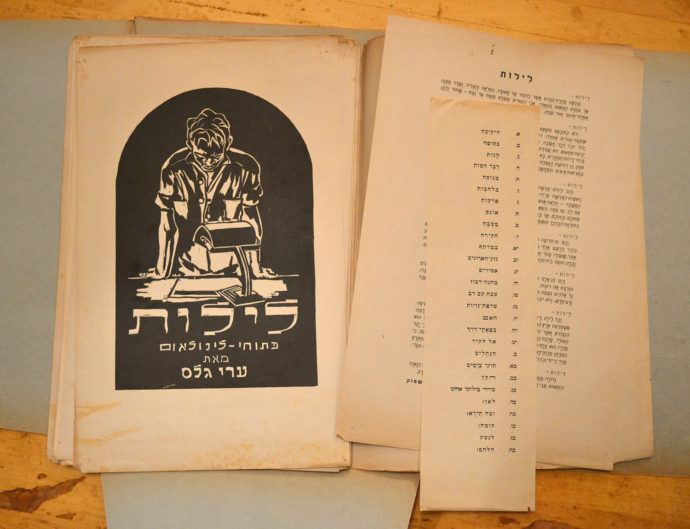

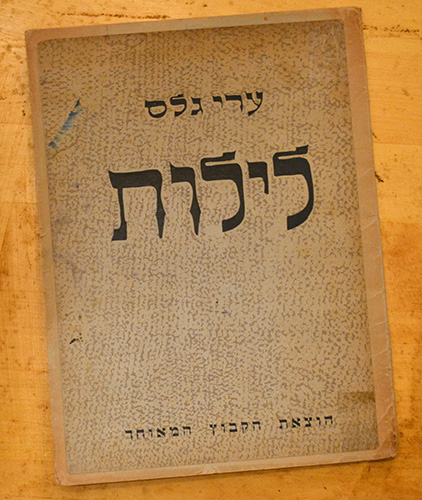

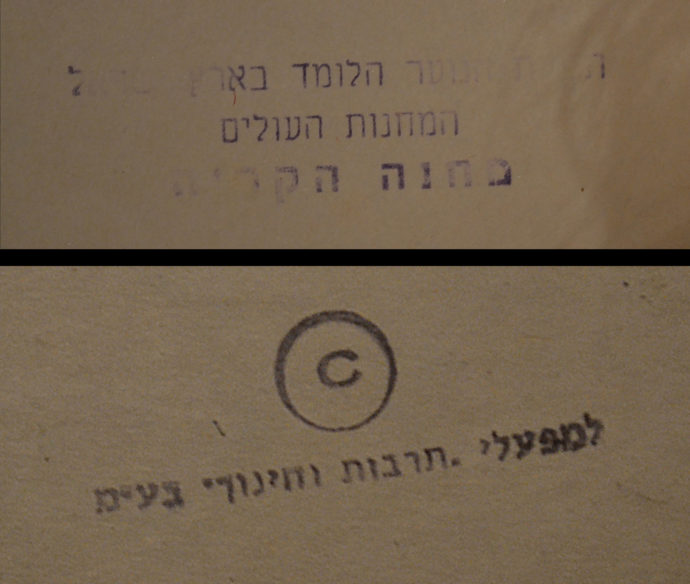

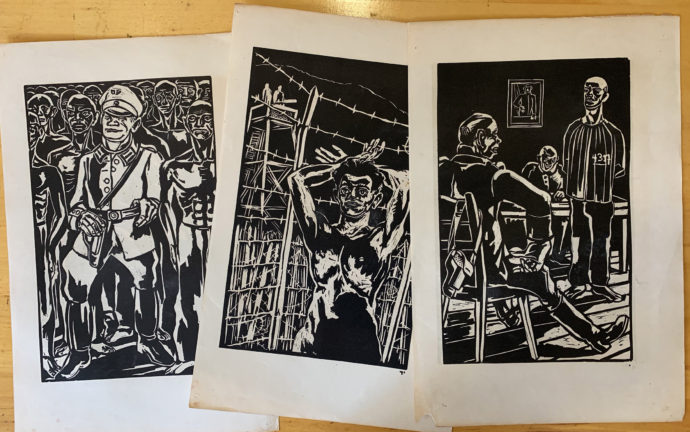

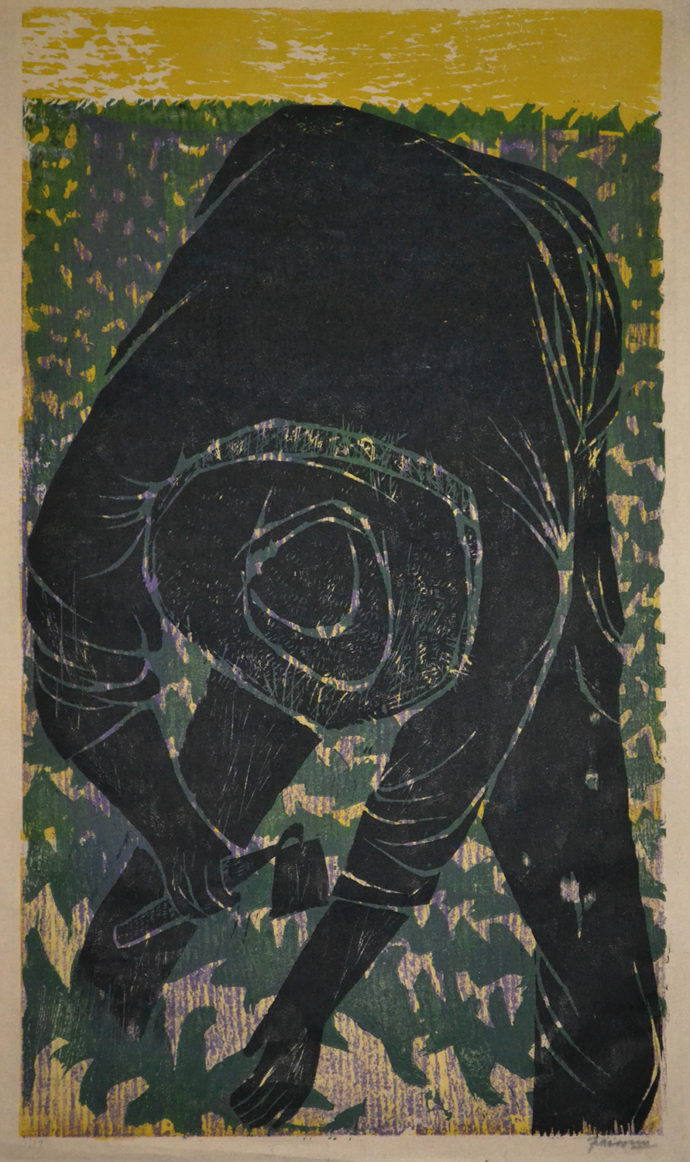

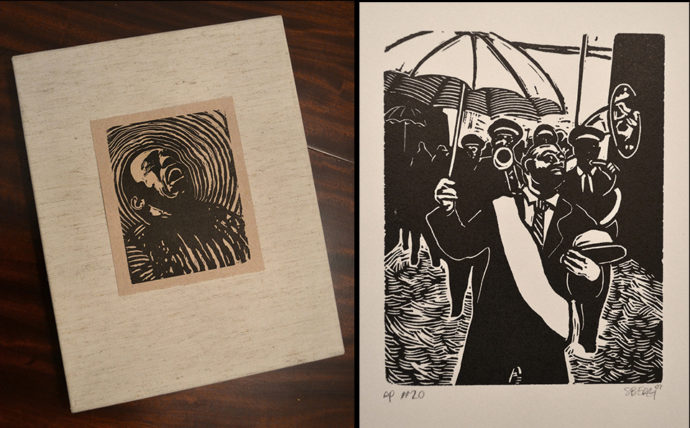

The artist Gan Kolski had a short tragic life. I borrowed the following from the Ackland Art Museum, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, website.

“The Polish-born artist Gan Kolski (1899-1932) lived in New York City on Horatio Street, near the burgeoning artistic neighborhood Greenwich Village. Kolski produced illustrations for the radical left magazine New Masses and participated in exhibitions by the John Reed Club, an organization for Marxist artists and intellectuals…. Although Kolski did not become as well known as some of his contemporaries, in part because his career was cut short by suicide at the age of only 33, his prints are an excellent example of the social realist aesthetic of the era.”

In a review in April, 2017, in the New York Times of Jules Stewart’s book “Gotham Rising: New York in the 1930s” Gan Kolski is quoted. According to the book, before leaping to his death from the George Washington Bridge over the Hudson, Kolski wrote: “If you cannot hear the cry of starving millions, listen to the dead, brothers. Your economic system is dead.”

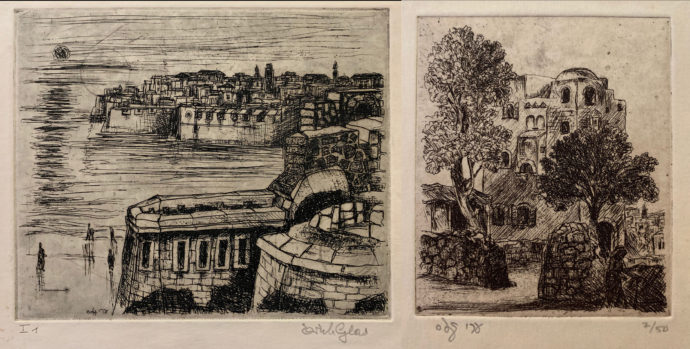

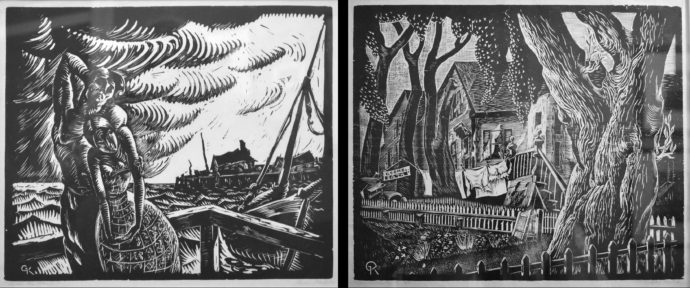

(Left) Gan Kolski, “After the Storm,” woodcut, c. 1928, 10 3/4″ x 12 15/16″ (Right) Gan Kolski, “Summer,” woodcut, 1928, ed. 50, 10″ x 12″ Since Kolski has done a print entitled Provincetown and a number of prints involving fishing fleets, I’m assuming both of these images derive from his stays in Provincetown.

Sawers was the third Kolski to enter my collection. I bought the pair above from the Mary Ryan Gallery in 1987.

Ever since a print dealer years ago confided in me that he was hoping to do a catalog raisonné on Gan Kolski, I had been hoping to do a full blog post on him. Unfortunately the dealer said his willingness to cooperate was contingent on him being able to buy a cache of Kolski prints from one individual. The price, according to the dealer, had always been too dear. Even when the dealer said he had given up on making that purchase, he refused to share some of what he knows about Kolski and his oeuvre.

Rainbows

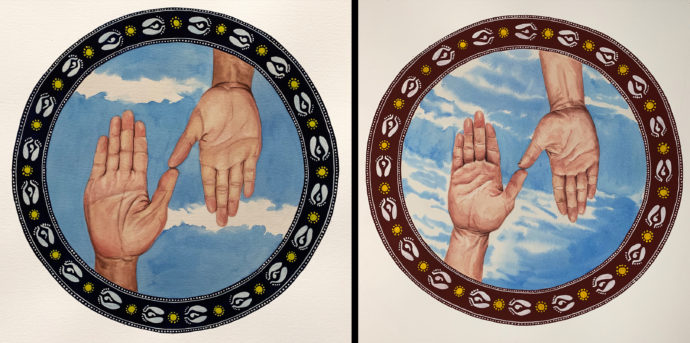

My fellow Amherst alumnus also played an after-the-fact part in my purchase of the following print.

Martin Petersen (Danish-American, 1866-1956), “Picknickers and Rainbows,” etching, 1930, 9 15/16″ x 11 11/16″

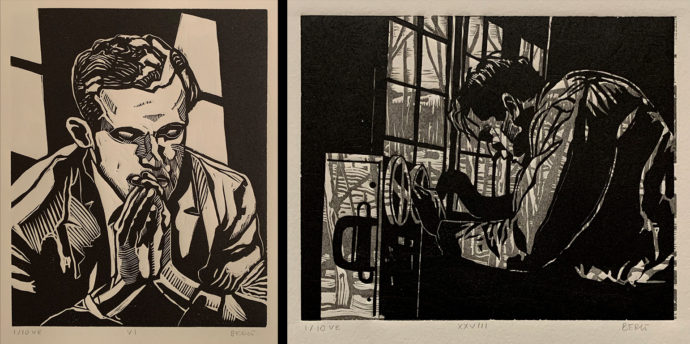

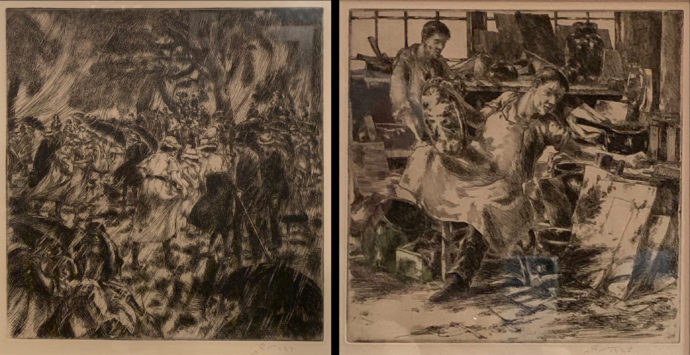

I’ve been eyeing this etching by Martin Petersen ever since I added two of his prints in 1997. One of them, A Summer Shower, Central Park (see below, left), is the yin of Picknickers and Rainbows‘s yang. They would make a perfect pair. So when Picknickers and Rainbows came up at auction, I was immediately interested. But there was one problem. It was being paired with another Petersen print that I wasn’t as interested in. Fortunately my friend did like the other print–The Metal Workers (see below, right)–and bought that from me.

(left) Martin Petersen, “A Summer Shower, Central Park, etching, 1937, 9 7/8″ x 9 3/8” and (right) Martin Petersen, “The Metal Workers,” etching, 1925, 8 15/16″ x 8 13/16″

Before I acquired my first Petersens in 1997, I bought the 1989 Petersen print catalog published by Kramer Gallery, Inc. in Minneapolis. It arrived with a price list enclosed. From Kramer I secured a copy of Petersen’s 1943 etching Along the Hackensack. And soon after I got A Summer Shower, Central Park from a vendor at the Capital Print Fair, held annually in Rosslyn, VA.

Leon and Wesley Kramer in their Petersen catalog listed 225 prints (in a few case there’s a fill-size print as well as a smaller print after the plate was cut down). The earliest print was dated 1916, the latest 1945. Most were etchings, a few drypoint and a few lithographs. The Kramers wrote: “It appears that Petersen did not usually predetermine an edition size for his prints, but made a small number of impressions initially and printed additional impressions as needed, dating them to the year printed, not the year the plate (or stone) was completed and first printed. A few of Petersen’s records indicate an edition size of 35 prints…. Petersen signed most prints with his initials only. The few that bear his full name in script were early works.”

In their biography of the artist, the Kramers wrote: “For fifty years Martin Petersen supported himself as a anatomical artist for the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University in New York. He joined the staff in 1897, and worked closely with George Summer Huntington illustrating books and doing drawings for the department.” Later they added: “Petersen also taught anatomy at the National Academy of Design, and plastic anatomy at Columbia.” Despite his being anatomical artist, I find many of Petersen’s human figure have a certain rubbery quality (lacking a normal bone structure) and occasionally with oversized hands. Yet his presentation of body language was fine.

Coincidentally, A Summer Shower, Central Park was the one print about which the Kramers have quotes from Petersen: “Petersen created art but did not talk about it. Whatever his guiding theories or philosophies were, he kept them to himself. Only one statement by the artist survives, and it concerns his prize-winning etching A Summer Shower, Central Park:

‘Some years ago, while sketching in Central Park, I was caught in a shower. From the sketches drawn at the time. the plate was made. As the work proceeded there were, however, a number of changes, some figures were eliminated and others added, so was to produce a well-balanced composition. Like all my plates it was entirely bitten, no drypoint….’

So on the mention of “prize-winning” I checked Albert Reese’s book American Prize Prints of the 20th Century (American Artist Group, inc., New York, 1949). He listed A Summer Shower, Central Park has having been awarded First Purchase Prize, Library of Congress, 1944. And Reese provided a more complete quote by the artist about the print. So after the phrase “no drypoint” Petersen said: “It was a very easy plate to print. All there is in the print is in the plate, no retroussage. Every printer can print it by wiping the plate clean, and will get about the same result in all the prints.”

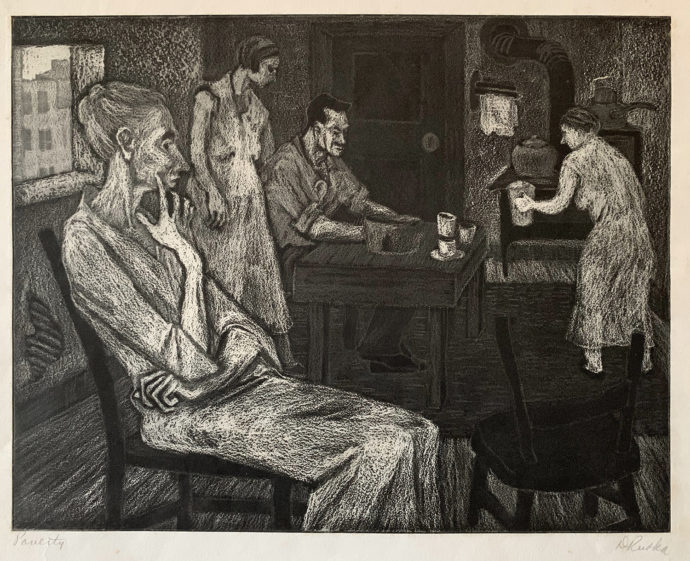

Poverty

This is one of those prints that I regret not buying years ago. Of all of her visual essays on the Depression this is the one I’ve liked the best. This copy appeared on eBay in the end of the summer and had no takers but me, possibly because the seller identified the medium as “aquatint” and didn’t add “etching” as well. This limited its visibility on eBay.

Elizabeth G. Seaton’s book Paths to the Press; Printmaking and American Women Artists, 1910-1960 (Marianna Kistler Beach Museum of Art, Kansas State University, 2006) has a two-pages spread on Rutka with an image of her print Striker’s Wife, also an aquatint. Of Slovenian-German descent, she attended the Cleveland School of Art, married the political editor for the Cleveland News, and began employment in the Cleveland WPA-FAP in 1936.

Seaton wrote: The artist spent most of her time in the program’s printmaking workshop, where she produced at least sixteen images, many of them powerful portraits of the unemployed and union workers and their families. Rutka’s commitment to visualizing labor issues coincided with her membership in Cleveland chapters of the left-leaning Artists Union (AU) and American Artists Congress, both of which called for government assistance for the unemployed and supported the period’s union drives.”

Since Poverty and Striker’s Wife share the same grainy textures, let me quote Seaton on Rutka’s aquatint method: “In Striker’s Wife Rutka used the intaglio method of crayon aquatint to render her lighter form in darkened space. In this technique she employed a greasy crayon over the plate’s aquatint areas before placing it in an acid bath. The areas covered by the crayon became the image’s haunting highlights, such was the angled, thin folds of the emaciated woman’s dress and the bony body of the child.”

As a member of the American Artists Congress, one of her aquatints Let ’em Eat Cake was exhibited in “America Today,” which the Congress organized. In the catalog, also called “America Today,” artist Alex R. Stavenitz wrote that 100 prints from 100 artists were to be part “of a nation-wide exhibition of duplicate exhibits to be held simultaneously in thirty American cities during the month of December, 1936.”

He added: “The exhibition, as a whole, may be characterized as ‘socially-conscious.’ It reflects a deep-going change that has been taking place among artists for the last few years–a change that has taken many of them not only to their studio window to look outside, but right through the door and into the street, into the mills, farms, mins and factories.”

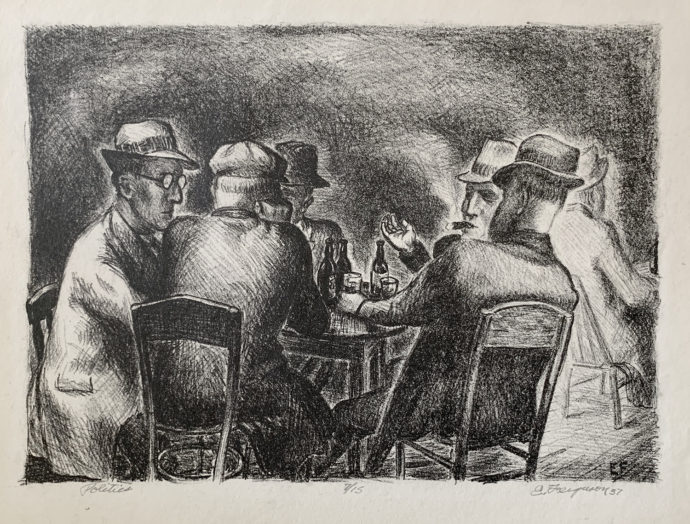

Politics

This print by Edward Ferguson was produced for the Flynt, Michigan, Federal Art Project, according to the Paramour Fine Arts website. Had it been produced in time for the American Artists Congress’s 1936 “America Today” exhibitions it would have been a perfect fit. So would have the other Ferguson lithograph in my collection.

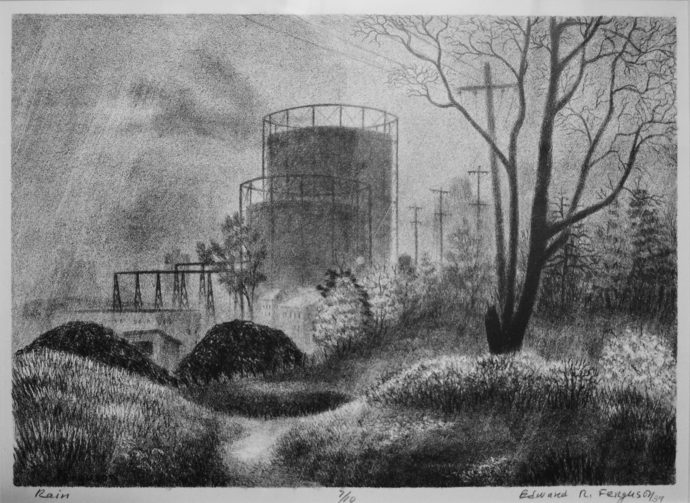

Rain was included in “The Federal Art Project: American Prints from the 1930s,” a 1985 exhibition at the University of Michigan Museum of

Art, Ann Arbor.